Many of us come to meditation for the first time to still our mind. We recognize that the source of suffering has something to do with the way our minds work (or don’t work) and we believe that by sitting still and taming our mind we will become calm and peaceful. One of the first things we might notice, however, when we sit still, is not peace but suffering—the first Noble Truth of the Buddha.

Many of us come to meditation for the first time to still our mind. We recognize that the source of suffering has something to do with the way our minds work (or don’t work) and we believe that by sitting still and taming our mind we will become calm and peaceful. One of the first things we might notice, however, when we sit still, is not peace but suffering—the first Noble Truth of the Buddha.

This may be the more obvious suffering that comes with old age, sickness, or death, but it also includes the more subtle forms, such as the agitation that arises as we try to maintain a certain posture and watch our breath for even a few minutes. The truth of suffering pops up right before our eyes in the very practice we hoped would lead to the end of suffering.

I teach a “Yoga for Zen Meditation” class because when we practice Hatha Yoga prior to sitting in meditation, we prepare the body and mind for stillness so that we can concentrate more deeply on the object of our meditation—be it a mantra, the breath, a koan, or simply being in the present moment. In my Yoga classes I start by reading a sloka or two from the Bhagavad Gita, or “The Song of the Lord.” That is our object of focus for the class, which we return to throughout the hour, just as we might return to our breath during meditation.

The Gita is a sacred text and an authoritative source for many Western practitioners of Yoga. It’s about an epic battle between the forces of good and evil, and how to navigate this dualistic world. The story itself is revered by many devout Hindus, some of whom recite it daily, as well as American Yoga practitioners. The Gita has profound teachings that are quite practical for everyday life, and, though they are not within the body of Soto Zen literature, there are obvious points of overlap that can regardless help us in meditation and lead to the end of suffering. I share a verse or two (from Swami Satchidananda’s book, The Living Gita), with a brief comment and how we can apply these verses on and off the Yoga mat. When I read the descriptions that Sri Krishna offers for meditation, my understanding sharpens as to some of the preconceptions about meditation that are particular to our culture and time.

Yoga practitioners should continue to concentrate their minds until they master their minds and bodies, and thus experience a state of solitude wherever they may be; then desires and possessiveness drop away. –Bhagavad Gita 6:10

And:

In order to excel, mentally control the senses, let go all attachments, and engage the body in Karma Yoga, selfless service. –Bhagavad Gita 3:7

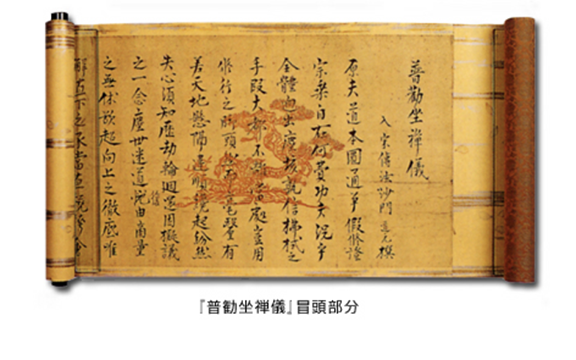

If applied appropriately, these verses can help any sincere practitioner of meditation experience their benefits directly. I use them in my own meditation practice. However, they are a little different from the instructions I received from my Soto Zen teachers, as well as those found in Zen Master Dogen’s Fukanzazengi, or “Universal Instructions of Zazen.” [see photo for a view of a page from this text]

In the Zen temples where I trained, there were numerous admonitions from my teachers to not control my mind or even to gain peaceful states. This is where confusion may arise for beginners not having access to teachers or spiritual communities, especially if they are not clear on what the “right” way is.

In the United States there is a cultural idea born in part from writings about the Bhagavad Gita and the Buddhist Sutras by such Transcendentalists as Ralph Waldo Emerson that meditation is about control, that this control requires one’s own individual efforts alone, and one will eventually experience peace if practiced for long enough. These ideas are fine but can be misleading when taken out of context.

Ralph Waldo Emerson was a huge proponent of self-reliance, living by one’s own conscience, and not unconsciously conforming to the norms of society. These are ideas that promote, even to this day, the importance of the individual and of individualism in general. While there is much merit to them, we may be unaware that individualism can lead to a kind of social cancer, according to the famous sociologist Robert Bellah[1], that pulls apart the bonds of society. The Sutras and the Gita were written in cultures that place social harmony above individual preferences, and so the role of community and teacher are paramount in understanding religious truths.

While there are recognized paths within Buddhism and Yoga such as the pratyekabuddhas (those that live in solitude without recourse to a teacher nor with interest in teaching others), these are rare and exceptional. Most Buddhists and yogis have teachers that they go to for instruction, especially at the beginning of their practice, but also throughout their lives. The formula for this in Buddhism is to take refuge in the Buddha, Dharma, and Sangha, and these refuges are recited daily. Implied in taking refuge is the recognition of our interdependence with others for our own well-being, and the need for experienced teachers.

Taking refuge, however, can come across for some people as weakness. The idea that we need to rely on something or someone other than ourselves may not sit well with us for various reasons (perhaps stemming from negative childhood experiences with authority figures). So, we may take it to an unintended extreme and think that we, as individuals, are totally responsible for our meditation practice, relying completely on our own efforts, not wishing for instruction. Thinking this, however, can easily obscure the reality of the moment because it dismisses our interdependence.

If meditation is not practiced with guidance from a teacher (even our inner guide), then when we try to control the mind, a danger is that our ego can be inadvertently invoked to do the job. When ego is in the driver’s seat, we miss the point. Spiritual practice can be misused to enhance our ego. One goal of Zen is to experience the dissolving of the ego-self, not the solidification of it. But what this means may not be so clear. It’s not that the ego has no place, or that it somehow dissolves forever once and for all.

Consider the following statements by some of my Zen Masters about Zen meditation (zazen):

- Let yourself be babysat by zazen. (Dai-En Bennage Roshi)

- You don’t do zazen. Zazen does zazen. (Shunryu Suzuki Roshi)

In other words, we don’t take the reins of our mind and try to direct it. We trust the Buddha or zazen itself to do that work. We let go of trying to control the process and put our faith in the practice and the guidance of our teachers and our own Buddha nature.

While the above verses in the Gita talk about controlling the mind, I don’t believe Sri Krishna is speaking to Arjuna’s ego as much as to his higher Self (his Buddha nature), and that he step up to the fullness of his humanity and to his purpose in life, which itself requires him to let go of any ego-centricity.

While the above verses in the Gita talk about controlling the mind, I don’t believe Sri Krishna is speaking to Arjuna’s ego as much as to his higher Self (his Buddha nature), and that he step up to the fullness of his humanity and to his purpose in life, which itself requires him to let go of any ego-centricity.

Arjuna then allows God, in the form of Sri Krishna, to take the reins of his own mind in the same way that Zen practitioners allow Buddha to take the reins of their mind. However, this might not be immediately obvious to the casual reader of the Gita, to the periodic Zen meditator, nor to a person steeped in a culture of self-reliance (as many are in the West).

If we can accept that there is something more than individual, ego-driven effort required when we come to meditation, and we can connect with the grace and blessings of the lineage we follow, then our grip loosens on the goal of practice—getting from “A” to “B” or from unenlightened to Enlightened—and we are better able to take in the backdrop immediately around us.

This reminds me of a cartoon image my teacher once shared with us of a person depicted driving a car amid an ordinary landscape. The street sign on the road read, “Spiritual experience ahead. Speed limit 0.” Or, as Sawaki Kodo Roshi once said, “The night train carries us along, even while we are sleeping.”

[1] See, Robert N. Bellah’s book, Habits of the Heart: Individualism and Commitment in American Life.

About the Author:

Daishin McCabe of Zen Fields in Ames is a 200-RYT Integral Yoga teacher, which he completed in 2011, and a Trauma Center Trauma Sensitive Yoga facilitator (TCTSY-F). He is a dharma heir of Dai-en Bennage Roshi, with whom he trained in monastic residence for 15 years; he has also practiced in Japan at several training temples and with Ven. Thich Nhat Hanh in France. He has a B.A. in Religion and Biology from Bucknell University. Daishin also teaches at the Shogaku Zen Institute and World Religions at the Des Moines Area Community College. He is grateful to be a member of the Pure Land of Iowa community in Clive, Iowa, where he also offers meditation retreats.

Daishin McCabe of Zen Fields in Ames is a 200-RYT Integral Yoga teacher, which he completed in 2011, and a Trauma Center Trauma Sensitive Yoga facilitator (TCTSY-F). He is a dharma heir of Dai-en Bennage Roshi, with whom he trained in monastic residence for 15 years; he has also practiced in Japan at several training temples and with Ven. Thich Nhat Hanh in France. He has a B.A. in Religion and Biology from Bucknell University. Daishin also teaches at the Shogaku Zen Institute and World Religions at the Des Moines Area Community College. He is grateful to be a member of the Pure Land of Iowa community in Clive, Iowa, where he also offers meditation retreats.