Photo: Reclining Buddha, Ayutthaya Thailand.

There are many stories in the Zen tradition that offer a perspective on sleep, such as the enlightenment of Ananda, where he stayed awake for several days on end trying to attain Great Liberation. He finally decides to give up on attaining enlightenment and get some rest. However, the moment his head hit the pillow he attains awakening. Even this story, however, seems to encourage not sleeping in a very literal way. Indian tradition, both Buddhist and Hindu, is replete with stories of home-leavers sitting in meditation for days on end without sleep. What are we to make of sleep today in our culture?

Today, I strongly believe these stories are not meant to be taken literally. They are meant to rouse one not just from physical sleep, but the unawareness of habit patterns—samskaras—that cause or create suffering for ourselves and others. We need to wake up to these samskaras because it’s only then that we can change them. If we are aware of how we create and cause others suffering, we will be highly motivated to more carefully analyze our behaviors and to evolve. In communal living there are many rules to follow. In a Zen temple, there is a way to do everything. There is a way to use the bathroom and wash your face. There is a way to eat food and to prepare food. There is even a way to wake up and go to sleep. Sleep, then, becomes a matter not of habit, but of something we need to practice.

In Zen Master Dogen’s Bendoho, he starts out writing about sleep. The monastic day, according to him, begins with sleeping. There is a way to enter into sleep. At Shogoji, where I trained, I was instructed to at least begin the night by sleeping on my right side. Sleeping on the right side is to mimic the Buddha’s entry into nirvana. I understood this as a way to remember the passing away of the Buddha, as well as the practice of entering the mind of the Buddha, as I went off to sleep.

Things got more interesting when I began my 200-hour Yoga teacher training in Yogaville. Here we learned about yogic sleep and I could not help but make parallels to what I had learned while living in Zen temples. It was recommended, for example, to sleep for the first five minutes or so on your left side because this helps stimulate heat in the body, to warm you up. Once you found that heat, then it was recommended to sleep on the right side because it stimulated the parasympathetic nervous system allowing the body to relax.

In the Zen temples, the practice of sleep was done mostly from a devotional or bhakti perspective. The physiological aspects were not considered. But at Yogaville, I learned that there were actually biological reasons for sleeping on your right side (and resting on your left). Furthermore, at the end of every Hatha Yoga class we practiced Yoga Nidra, or Deep Relaxation. This was also referred to as yogic sleep.

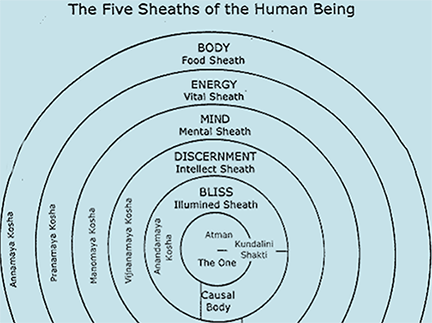

Yoga Nidra, in my understanding of it, is built on the idea that at the core of one’s being is the Atman. The model, one of many, used in Yoga Nidra is that of the koshas or layers. The body is said to be comprised of five koshas. Incidentally, the Buddha taught that the self is comprised of five aggregates which, while similar are not exactly the same as the koshas.

Photo: Five koshas of yogic science.

The first layer is the food body: Anomaya Kosha. This refers to one’s physical body. It’s our muscles, tissues, skin, hair, intestinal organs, etc. The Buddha called this the “form” aggregate.

The second layer is the Pranamaya Kosha. This refers to the breath and the fact that respiration is taking place—something is moving this body as long as we are alive, even when we don’t exert energy into movement. The Buddha talked about the breath body, but not as one of the five aggregates. In the “Sutra on Mindful Breathing,” Buddha goes into great detail as to how to attend to the breath. Breath is considered as part of the physical body, not a separate layer as in the five kosha model.The third layer is the Manomaya Kosha, or the emotional/mental body. Buddha talked about the aggregates of “feelings, perceptions, and mental formations.” He said that there are basically three kinds of feelings: pleasant, unpleasant, and neutral. Perception has to do with our biases in the way that we perceive the world. In some systems of Buddhist thought there are considered to be some 52 mental formations. Manomaya Kosha may loosely parallel with these three aggregates of feelings, perceptions and mental formations.

When we go to a medical doctor, we may look only at our physical body, and we as a society consequently place a lot of emphasis on our physical body’s functionality. If we need help with our mind, we go see a psychologist. The two aspects of self—physical and emotional/mental—in American life and education are by-in-large considered separate. But in the yogic (and Zen Buddhist) worldview, body/mind/emotion cannot be separated. In Yoga Nidra we can access this emotional body by bringing our awareness to it. Without a physical body, there is no emotional body.

The fourth layer is the Vijnanamaya Kosha, or the witness body. I believe this may roughly correspond with the Buddhist aggregate of “Consciousness.” This is that aspect of the Self that remains a by-stander of all experience. It simply watches without reacting. In Zen meditation, when we are watching our thoughts, we are using and developing this aspect of the Self, we just don’t refer to it as such, or as a distinct body. But in Yoga Nidra it’s considered the 4th layer of the body.

The fifth layer is called the Anandamaya Kosha or the bliss body. Ananda, incidentally, was the name of the Buddha’s cousin who was awakened, if you recall, when his head hit the pillow! In Zen, at least how it has been presented to me, we don’t talk a lot about bliss. It’s recognized but not as an aim of practice. All mental states, we are admonished, are not to be clung to, even ones that appear to be “good.” It’s been discouraged to “feel good” in meditation because, as one of my teacher’s would say, “We don’t go off into la-la land.” Meditation is not a high that takes you away from the reality of the present moment. We cannot forget the suffering of the world. These are important points, I think, to keep in mind.

Photo: The five aggregates.

Yet, Zen Master Dogen talked about Zazen as being, “Anraku no Ho Mon” or “The Dharma Gate of peace and joy.” Furthermore, one of the three body’s (Trikaya) of the Buddha in Mahayana Buddhism is referred to as the “Bliss Body” or Samboghakaya. This is the body of the Buddha that is not bound by time and space. So, we can find parallels to the yogic tradition. The Dharmakaya refers to the truth, as it appears in reality, beyond likes and dislikes. It bears some resemblance to the Vijnanamaya Kosha in the yogic model.

In the yogic tradition, as I have been exploring it, speaking openly about bliss is not discouraged or frowned upon. If we look at the Yoga Sutras, we can find a place for both the highs and the lows of practice. An important term to know, for example, is “tapas.” This is the burning or purifying that results upon the determination to liberate oneself or others. It’s not necessarily comfortable to practice tapas (also translated as “asceticism”), but it is nonetheless a part of the yogic tradition. So, while bliss is talked about, there is a larger context that shows the dynamism of what it means to be alive. This includes an acceptance of discomfort.

When I practice Yoga Nidra, and when I teach it in my Integral Yoga classes, I go through each of the five koshas one-by-one beginning with the food body and ending with the bliss body. We do the practice laying down on our backs. When we get to the bliss body, we stay there, lingering for 1-5 minutes depending on the class. This bliss body, I have witnessed in myself and others, can be very rejuvenating and healing. It puts us into a very deep relaxation. Sometimes when we come out of it, we have no idea how long we’ve been resting for.

Regardless of my feelings about sleep, I’ve come to look at it as an opportunity to practice. Nights when I’m restless I may choose to wake up and sit in meditation. Or I may choose to remain lying down practicing Yoga Nidra. I explore how it is to sleep on the left versus the right side of my body. At times, I consider the Buddha, resting on his right side as he enters nirvana. Sleep can be a part of our practice. We can become curious about it and take it, perhaps, more seriously than we have yet done.

About the Author:

Daishin McCabe of Zen Fields in Ames is a 200-RYT Integral Yoga teacher, which he completed in 2011, and a Trauma Center Trauma Sensitive Yoga facilitator (TCTSY-F). He is a dharma heir of Dai-en Bennage Roshi, with whom he trained in monastic residence for 15 years; he has also practiced in Japan at several training temples and with Ven. Thich Nhat Hanh in France. He has a B.A. in Religion and Biology from Bucknell University. Daishin also teaches at the Shogaku Zen Institute and World Religions at the Des Moines Area Community College. He is grateful to be a member of the Pure Land of Iowa community in Clive, Iowa, where he also offers meditation retreats.

Daishin McCabe of Zen Fields in Ames is a 200-RYT Integral Yoga teacher, which he completed in 2011, and a Trauma Center Trauma Sensitive Yoga facilitator (TCTSY-F). He is a dharma heir of Dai-en Bennage Roshi, with whom he trained in monastic residence for 15 years; he has also practiced in Japan at several training temples and with Ven. Thich Nhat Hanh in France. He has a B.A. in Religion and Biology from Bucknell University. Daishin also teaches at the Shogaku Zen Institute and World Religions at the Des Moines Area Community College. He is grateful to be a member of the Pure Land of Iowa community in Clive, Iowa, where he also offers meditation retreats.