Photo: Hatha Yoga was to play an important role in Ramu’s life.

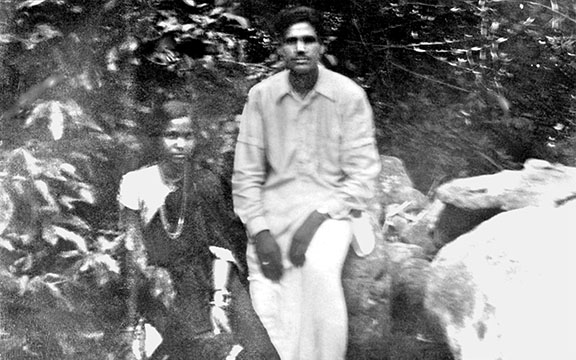

During the time Ramaswamy (Swami Satchidananda’s birthname was Ramaswamy) served as the manager of the Perur Temple in 1937, he had become well-acquainted with one of the families who was very active and helpful in the management. In fact, the head of the family had once been a trustee of the Temple. The daughter of this gentleman regularly visited the Temple to worship and pray.

If Ramaswamy was going to marry, which his family was doubtful about given his spiritual leanings, she seemed to be right choice and both families gave their blessings. Ramaswamy’s family was overjoyed and filled with relief, particularly after the birth of first one and then another son. They were confident that Ramaswamy was leading an exemplary family life. Family life went on smoothly, contentedly, and lovingly. Or, so it seemed.

Ramaswamy began to have some premonitions, some would say anxieties, during his daily commute to work. Thoughts would arise of the loss of his wife, his family life, and how he would feel if this happened. When he reflected on those feelings he realized, ‘I love her so much, but if God decides to take her away, who can stop it? I can’t worry about these things. I will have to take it as God’s will.’ Ramaswamy’s faith would indeed be sorely tested. Five years into his marriage, his wife suddenly disappeared.

Prior to their marriage, she had been involved in a theater and dance community, which she loved. While she was unmarried, her parents indulged this interest, thinking she would give this all up and become a wife and mother. But, she fell in love with another dancer and wanted to marry him. In those days, “love marriages” were very rare and, instead, marriages were predominantly arranged to ensure financial stability and security particularly for the bride-to-be and her family. This involved dowries that were to be presented to the groom’s family, something that later, as Swami Satchidananda, he would advocate against. Ramaswamy, coming from a well-to-do family, and given his devotional nature, was seen to be the ideal groom by the bride-to-be’s family. The belief was that with these practical foundations firmly in place, the couple would have the necessary conditions to grow and nurture love for each other over time. This pragmatic approach prioritized familial alliances, social status, and economic benefits, with the expectation that affection and companionship would naturally develop within the marriage.

Rare photo of Ramaswamy and his wife, early 1940s, South India.

It seemed that Ramaswamy’s wife had acquiesced to her parents’ wishes that she marry him, though she had promised her heart to another, leaving her deeply unhappy in her marriage. Soon after his wife’s disappearance, the close-knit community in which Ramaswamy was raised would come to find out that his wife had left to be with the dancer, a Muslim man she’d been in love with prior to marrying Ramaswamy. This left both families to grapple with the fallout of her decision.

As Hindus, especially during that time period, her family would never have approved her marrying anyone outside of their faith. Without her parents’ approval, she would not have been allowed to marry, let alone leave the home if they suspected she was communicating with the Muslim man. But now, outside of her parents’ household and married to Ramaswamy, she had more freedom and was able to leave of her own free will. Though surprised by this turn of events that had confirmed his premonitions, Ramaswamy felt that these had prepared him to receive the news with a sense of calm. He realized there was nothing he could do and he now began to think of the welfare of his two young children left in his care.

In their tight-knit and very traditional community, a wife running away from her husband was considered a very scandalous event that challenged societal norms. Ramaswamy’s family and the surrounding community were shocked and unable to reconcile this act with their cultural values. They did not want anyone to even speak of this. Such an act was so disgraceful and incomprehensible that Ramaswamy’s wife was referred to as having “died” to him, his family, and the community. They insisted that her name never be mentioned again, and she was effectively erased from the collective memory, highlighting the community’s adherence to tradition and the severe social repercussions for defying it. Out of respect for the customs at that time, Ramaswamy abided by their wishes and, thereafter, when asked what had happened to his wife he would say that she had “died.”

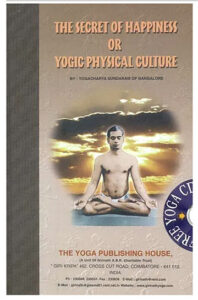

Ramaswamy spent the next several months reflecting on the premonitions he’d had about his wife and what they may have been pointing to—perhaps a departure from the life he had been living? He began to feel that, while he loved his family and enjoyed the businesses he was involved in, perhaps householder life was not his calling. So, he started to immerse himself in spiritual studies and he began an ardent practice of Hatha Yoga. Ramaswamy found his initial inspiration in the practice of Hatha Yoga through early pioneering texts. One such influential book was The Secret of Happiness or Yogic Physical Culture by a Tamil lawyer and Yoga Guru, Seetharaman Sundaram (known, when not practicing law, as Yogacharya Sundaram), which was published in 1928. This groundbreaking work was the first Yoga handbook to be published in English.

Photo: Cover of Yogarcharya Sundaram’s book.

Yogacharya Sundaram had been inspired by Swami Kuvalayananda’s Hatha Yoga system. Swami Kuvalayanandaji (formerly Dr. J. G. Gune), is considered a pioneer of “scientific Yoga” and he would also become a strong influence in the young Swami Satchidananda’s study and practice of Hatha Yoga and Yoga therapy. Though Swami Kuvalaynanda was spiritually inclined and idealistic, he was, at the same time, a strict rationalist. He sought scientific explanations for the various psychophysical effects of Yoga he experienced. From 1920 to 1921, he investigated the effects of the yogic practices of uḍḍiyana bandha and nauli on the human body with the help of some of his students in a laboratory at the State Hospital, Baroda. He explained:

“In our Indian effort to scientifically investigate the field of Yoga, science is looking not only at the heart of the human being

but also at its mind and spirit and is trying to develop a perfectly integrated personality, not only for an individual but for the whole of mankind.”

In 1924, Swami Kuvalaynanda founded the Kaivalyadhama Health and Yoga Research Center in Lonavla, India, to provide a laboratory for his scientific study of Yoga. His research agenda, although covering a variety of yogic practices which he divided into asana, pranayama, kriyas, mudras, and bandhas, resulted in a detailed study of the physiology involved during each such practice. Swami Satchidananda had the opportunity to spend time with Swami Kuvalayanandaji before his passing in 1966. In the years that followed, Sri Swamiji continued to visit the Kaivalyadhama Center, several times bringing devotees there, some of whom were working in the medical field.

At the same time as founding his research institute at Lonavla, Swami Kuvalayananda started Yoga Mimansa, the first journal devoted to scientific investigation into Yoga, published quarterly. It covered experiments on the effects of asanas, kriyas, bandhas, and pranayama. His early trailblazing research would draw not only students from Yale and other western universities during that time, but also devoted students like Sri T. Krishnamacharya, one of the great Yoga masters. Sri Krishnamacharya’s students included Sri B.K.S. Iyengar, Mataji Indra Devi, and his son, Sri T.K.V. Desikachar, who became renowned for his contributions to Yoga therapy.

Photo: Swami Kuvalayananda

Yogacharya Sundaram, deeply inspired and informed by Swami Kuvalayananda’s approach and research, developed detailed instructions and the inclusion of stages for adopting each asana. This marked a significant innovation, making the practice systematic and precise, something entirely missing from texts like the 14th century Hatha Yoga Pradipika. This approach, which emphasized controlled and mindful execution of poses, laid the groundwork for the modern practice of Hatha Yoga. The format, essentially a guide with the name of each item, a description in text, and a photograph (each pose demonstrated by Sundaram himself), was adopted by most of the Yoga manuals that followed, including Swami Satchidananda’s book, Integral Yoga Hatha.

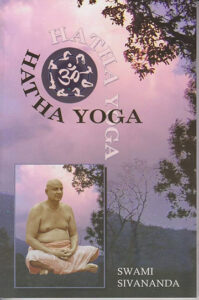

The other book that Ramaswamy read during this time and that would become pivotal in his life was the 1939 edition of Hatha Yoga by the Himalayan sage, Sri Swami Sivanandaji Maharaj. This book begins with a letter from Swami Sivananda stating:

“Hatha Yoga is a Divine blessing for attaining success in any field. Body and mind are instruments which the practice of Hatha Yoga keeps sound, strong, and full of energy. It is a unique armour of defence to battle opposing forces in the material and spiritual field. By its practice you can control Adi Vyaddhi [disturbed mind leading to physical disease] andattain radiant health and God-realisation. Become a spiritual hero full of physical, mental and spiritual strength.”

In 1924, Sri Swami Sivanandaji renounced his medical career and took sannyasa (monastic vows) in Rishikesh, where he was initiated into the Dasnami Order by Swami Vishwananda Saraswati. In Rishikesh, Swami Sivananda engaged in the study and practice of various forms of Yoga, including Hatha Yoga. He studied classical texts such as the Hatha Yoga Pradipika, Gheranda Samhita, and Siva Samhita, which are foundational texts in Hatha Yoga. Swami Sivananda’s journey into Hatha Yoga was marked by his medical background, intense self-study, and practice of these classical Yoga texts, and most likely Swami Kuvalayananda’s and Yogacharya Sundaram’s texts as well.

Photo: Cover of Swami Sivananda’s book.

Swami Sivanandaji’s Hatha Yoga book remains a valuable resource for practitioners. It contains not only a systematic course of asanas, but includes the entire Hatha Yoga system, including shat karmas, mudras, bandhas, pranayama, meditative poses, as well as Yoga therapy, teachings on the subtle body, chakras, and kundalini. Ramaswamy began a steady practice of Hatha Yoga following Swami Sivananda’s text and he also decided that should he be able to become a dedicated sadhu, he would somehow make his way from South India all the way to the foothills of the Himalayas to be able to have darshan of Swami Sivanandaji.

Less than a decade later, Ramaswamy would indeed make his way to Rishikesh and to the holy feet of the great sage who would become his Guru and initiate him into the Dasnami Order of Sannyas as Swami Satchidananda. Several decades after that blessing and receiving the title “Yogiraj” from his Guru, Swami Satchidananda, would become renowned for his profound influence on the spread of Hatha Yoga in the West, as well as Integral Yoga, but we’re getting ahead of this part of the odyssey.

After several months of observing Ramaswamy becoming more and more interested in spiritual studies, Srimati Velammai (his mother), became worried and said, “Perhaps it’s time for you to consider remarrying, at least for the sake of the children.” Ramaswamy explained that he felt that the premonitions he had about losing his wife, and then actually losing her, had prepared him, as well as signaled a new path ahead for him. He felt that he should not remarry, but instead devote himself to a deeper purpose that was drawing him. His parents were not altogether happy about this development and grew even more concerned that Ramaswamy was perhaps contemplating becoming a wandering sadhu.

The idea came that seemed to satisfy both Ramaswamy’s spiritual yearnings and his parents’ concerns: He could take some time to devote himself to spiritual pursuits, while still living at home, and see what unfolded.

About the Author: