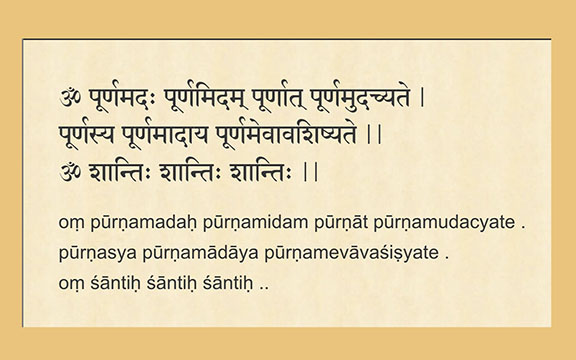

Shanti mantra from Brihadaranyaka Upanishad and Ishavasya Upanishad.

This shloka is a Shanti mantra from Brihadaranyaka Upanishad and Ishavasya Upanishad. This is an innocuous looking verse: one noun, two pronouns, three verbs and a participle for emphasis. Yet, someone once said: “Let all the Upanishads disappear from the face of the earth. I don’t mind so long as this one verse remains.” Can one small verse be so profound?

This Pūrnam, the single noun in the verse, is a beautiful Sanskrit word which means completely filled—a filled-ness which (in its Vedic scriptural sense) is wholeness itself, absolute fullness lacking nothing whatsoever. Adah, which means ’that’, and idam, which means ’this’, are two pronouns each of which, at the same time, refers to the single noun, Pūrnam: Pūrnam adah – completeness is that, Pūrnam idam – completeness is this.

[ Translation of Shloka by Sri Swami Satchidananda:

That is full, this also is full.

This Fullness came from that Fullness.

Though this Fullness came from that Fullness.

That Fullness remains forever full.

Om Shāntih Shāntih Shāntih ]

Adah, that, is always used to refer to something remote from the speaker in time, place or understanding.Something which is remote in the sense of adah is something which, at the time in question, is not available for direct knowledge. Adah, that, refers to a Jñeya vastu, a thing to be known, a thing which due to some kind of remoteness is not present for immediate knowledge but remains to be known upon destruction of the remoteness. Idam, this, refers to something not remote but present, here and now, immediately available for perception, something directly known or knowable. Thus it can be said that adah refers to the unknown, the unknown in the sense of the not-directly known due to remoteness, and idam refers to the immediately perceivable known…

So in context, adah, the pronoun ’that’, stands for what is meant when I say, simply, “I am”, without any qualification whatsoever. ’That’ so used as ’I” means Ātmā, the content of truth of the first person singular, a Jñeya vastu, a to-be-known, in terms of knowledge. When that knowledge is gained, I will recognize that I, Ātmā, am identical with limitless Brahman – all pervasive, formless and considered the cause of the world of formful objects.

So far, then, the first two lines of the verse read:

Pūrnam adah – completeness is I, the subject Ātmā, whose truth is Brahman, formless, limitlessness,considered creation’s cause; Pūrnam idam – completeness is all objects, all

things known or knowable, all formful effects, comprising creation.

Pūrnam, Completeness

Therefore, when it is said that aham, I, am Pūrnam and idam, this, is Pūrnam, what is really being said is that there is only Pūrnam. Aham, I, and idam, this, traditionally represent the two basic categories into one or the other of which everything fits. There is no third category. So if aham and idam, represent everything and each is Pūrnam , then everything is Pūrnam. Aham, I is Pūrnam which includes the world. Idam this, is Pūrnam which include me. The seeming differences of aham and idam are swallowed by Pūrnam – that limitless fullness which shruti (scripture) calls Brahman.

If everything is Pūrnam, why bother with ’that’ and ’this’? My everyday experience is that aham, I, am a distinct entity separate and different from idam jagat, this world of objects which I perceive. My experience is that I see myself as not the same at all as idam, this. When I hold a rose in my hand and look at it, I, aham, am one thing and idam, this rose I see, is quite another. In no way is it my experience that I and the rose are the same. We seem quite distinct and separate. Because shruti tells me that I, aham, and the rose, idam, both are limitless fullness, Pūrnam.

Based on one’s usual experience, it is very difficult to see how either aham, I or idam, this can be Pūrnam;and, even more difficult to see how both can be Pūrnam. Pūrnam, completeness, absolute fullness, must necessarily be formless. Pūrnam cannot have a form because it has to include everything. Any kind of form means some kind of boundary; any kind of boundary means that something is left out – something is on the other side of the boundary. Absolute completeness requires formlessness. Sastra (scripture) reveals that what is limitless and formless is Brahman, the cause of creation, the content of aham, I. Therefore, given the nature of Brahman by shruti, I can see that Pūrnam is another way for shruti to say Brahman. Brahman and Pūrnam have to be identical; there can only be one limitlessness and that One is formless Pūrnam Brahman.

Photo by Greg Rakozy via Unsplash.

Thus, the verse is telling me that everything is Pūrnam. Pūrnam has to be limitless, formless Brahman. Thus, shruti says there is nothing but fullness, though fullness appears to be adah, that (I), and idam, this (objects). In this way, shruti acknowledges duality – experiences of difference – and then, accounts for it by properly relating experience to reality. Shruti accounts for duality by negating experience as nonreal, not as nonexistent. Thus, to the Vedantin, negation of duality is not a literal dismissal of the experience of duality but is the negation of the reality of duality. If one to be Pūrnam, a literal elimination of duality is required.

Shruti is not afraid of experiential duality. The problem is the conclusion of duality – not experience of duality.The problem lies in the well-entrenched conclusion: “I am different from the world; the world is different from me.” This conclusion is the core of the problem of duality – of samsāra. Shruti not only does not accept this conclusion but contradicts it by stating that both ’I’ and ’this’ are Pūrnam. Shruti flatly negates the conclusion of duality.

The Upanishad vākyās (statements of ultimate truth), when unfolded in accordance with the sampradāya (the traditional methodology of teaching) by a qualified teacher are the means for directly seeing – knowing – the nondual truth of oneself. The teacher, using empirical logic and one’s own experience as an aid, wields the vākyās of the Upanishads as pramāna to destroy one’s ignorance of oneself.

For aham to be idam and for idam to be aham they must have a common efficient and material cause.Consider an empirical example, a single pot referred to both as ’that’ and ’this’: for ’that’ flower pot which I bought yesterday in the store to be the same as ’this’ flower pot now on my window sill, there has to be the same material substance and the same pot maker for both ’that’ and ’this’. It is clear that this ‘twoness’ of ‘that’ pot and ‘this’ pot is functional only; the two pronouns refer to the same thing which came into being in a single act of creation.

Is it possible to discover a situation in which two seemingly different things are in fact the non-different effects of a single, common material and efficient cause? Yes, in a dream. Our ordinary dream experience provides a good illustration of a similar situation. In fact, a dream provides a good example not only of a single cause which is both material and efficient, but also of effects which appear to be different but whose difference resolves in their common cause. In a dream both the dream’s substance and its creator abide in the dreamer. The dreamer is both the material and efficient cause of the dream.

Furthermore, in a dream there is a subject-object relationship in which the subject and object appear to be quite different and distinct from each other. The dream world is a world of duality. The dream aham, I, is not the same as the dream idam, this. But this dream difference is not true – is not real. When I dream that I am climbing a lofty snow-covered mountain, the weary, chilled climber, the dream aham is nothing but I, the dreamer; the snow-capped peak, the rocky trail, the wind that tears at my back, the dream idam, the dream object, are nothing but I, the dreamer. Both subject and object happen to be I, the dreamer, the material and creative cause of the dream.

From formless, chain-free gold comes formful, chain-shaped gold. Is there any real change in gold itself? There is none. Svarnāt svarnam – from gold, gold. There is no change.

Pūrnat Pūrnam – from completeness, completeness. What a beautiful expression! It explains everything.

I am Pūrnam, completeness, a brimful ocean, which nothing disturbs. Nothing limits me. I am limitless.Waves and breakers appear to dance upon my surface but are only forms of me, briefly manifest. They do not disturb or limit me. They are my glory – my fullness manifest in the form of wave and breaker. Wave and breaker may seem to be many and different but I know them as appearances only; they impose no limitation upon me – their agitation is but my fullness manifest as agitation; they are my glory, which resolves in me. In me, the brimful ocean, all resolves. I, Pūrnam, completeness, alone remain. Om Shāntih Shāntih Shāntih

[Note: Learn from Sri Swami Satchidananda how to chant this shloka here: https://soundcloud.com/yogawisdom/22-om-purnam-adah ]

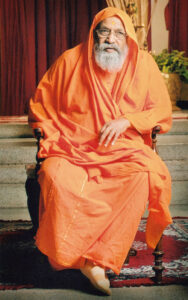

About the Author:

A teacher of teachers, Swami Dayananda taught many resident in-depth Vedanta courses in India in the US. Through these courses Sri Swamiji created many full-fledged teachers of Vedanta who are sharing the wisdom of Vedanta throughout India and in different parts of the world. Under his guidance, various centers for teaching of Vedanta have been founded around the world. Among these, there are three primary Institutes in India at Rishikesh (Arsha Vidya Pitham, Swami Dayananda Ashram), Coimbatore (Arsha Vidya Gurukulam, Anaikatti), Nagpur (Arsha Vijnana Gurukulam) and one in the U.S. at Saylorsburg (near NJ), Pennsylvania (Arsha Vidya Gurukulam). There are more than one hundred centers in India and abroad that carry on the same tradition of Vedantic teaching.

A teacher of teachers, Swami Dayananda taught many resident in-depth Vedanta courses in India in the US. Through these courses Sri Swamiji created many full-fledged teachers of Vedanta who are sharing the wisdom of Vedanta throughout India and in different parts of the world. Under his guidance, various centers for teaching of Vedanta have been founded around the world. Among these, there are three primary Institutes in India at Rishikesh (Arsha Vidya Pitham, Swami Dayananda Ashram), Coimbatore (Arsha Vidya Gurukulam, Anaikatti), Nagpur (Arsha Vijnana Gurukulam) and one in the U.S. at Saylorsburg (near NJ), Pennsylvania (Arsha Vidya Gurukulam). There are more than one hundred centers in India and abroad that carry on the same tradition of Vedantic teaching.