Fr. Clooney in his office at Harvard.

It was 1995, and I had just arrived at St. John’s University in New York, fresh from a summer spent at a Hindu monastery. I was on a spiritual quest—a journey sparked, in part, by post-traumatic symptoms I had only just begun to name. Perhaps they were gifts in disguise, born from growing up under a totalitarian regime in Poland and later arriving here as an undocumented immigrant.

The first two classes I took were on Christian mysticism and Hindu mysticism. I was seeking a bridge between the holy peace I had touched at the monastery and the path of Jesus—the one I was tentatively returning to, though I didn’t yet know it. My English was functional: I could read well, but I was shy to speak, afraid people wouldn’t understand me. My voice felt small.

So I spent long stretches in the library each day, broken only by chapel prayers. I lingered in the Hindu-Christian section, drawn to an encounter with the sacred as glimpsed through a tradition not my own—one that invited silence and a meeting of hearts. It was there, in the footnotes, that I first encountered his name: Francis X. Clooney, S.J. Who is this Jesuit, I wondered, who ventured so deeply into the heart of another tradition?

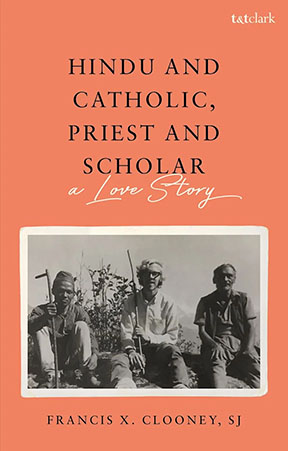

Now, reading Hindu and Catholic, Priest and Scholar: A Love Story all these years later, I find myself returned to that season of longing and discovery. Clooney is widely known as a careful, contemplative scholar of Hindu-Christian dialogue—someone who reads sacred texts slowly, with reverence and nuance, seeking not just understanding but encounter. But in this book, the subject is not a tradition or a text. It is him—his choices, his longings, his search for God. Clooney’s book echoes Dorothy Day’s sense that writing a memoir is like going to confession: It only works if you’re honest. In telling that story, he invites us to reflect on our own.

His life-defining experience came on a hot Brooklyn night in 1966. He was 15, sleepless, alone in his childhood bedroom. “I felt a very strong presence, a physical nearness I knew to be God…entering into me, piercing me, taking hold of me deep inside. It was an intrusion, a kind of awakening…no words, no visions, just being touched, taken over inside, all in a moment.” That moment became the foundation for everything: “From that moment on…I could from now on be only for God.”

Reading the memoir, I was reminded again and again how important it is to pay attention to the sacred moments in our lives. They are not just memories. They are directives. The first step is learning to listen. The second, harder step is learning to trust them. That is what Clooney did. And what unfolds is a life shaped by fidelity to that early whisper. It is not a heroic tale. It is not about conquest or arrival. It is about staying close to what called him in the first place.

That moment didn’t just lead him to the Jesuits; it changed how he lived the life that followed. When Jesuit spirituality, including the Spiritual Exercises of St. Ignatius, felt too busy, too structured, he adjusted. “I developed my own way of appropriating this spirituality,” he writes, balancing the rigor of Jesuit practice with Ignatius’ spirit of experimentation. Like Ignatius, he trusted that “if at any point I find what I am seeking, there I will repose.”

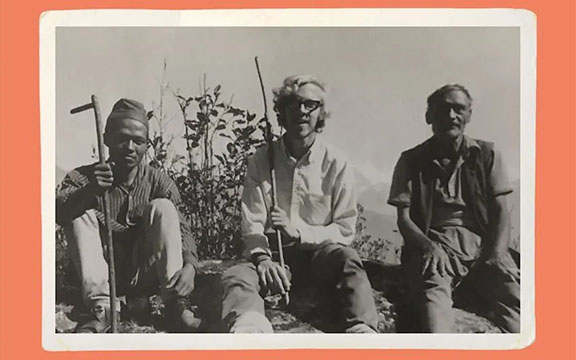

Photo: Fr. Clooney (center) in Nepal, 1973.

That kind of listening—patient, discerning—became a pattern. After returning from teaching in Kathmandu, the theology he studied in the West no longer felt sufficient. Something had shifted. “I still wanted to be a Jesuit priest,” he writes. “But I wanted, needed, to do this in my own way. My two years in Nepal made this need all the more acute. I wanted to be a Jesuit deeply changed by Hindu learning.”

Confusion followed. And again, God came. One morning, standing on the rocks by the ocean, bathed in the rising sun, he felt it: a warmth, a presence, a quiet reassurance. “You are in the right place. Stay where you are. Do not panic or run. All will be well.” After that, the ground settled beneath him.

Eventually, when he dove deeply into Hindu texts and languages, he didn’t study from a distance. He let the tradition touch him. He studied. He prayed. He listened. He entered into Hinduism through mentorship and immersion, approaching it from within in ways still uncommon among Western practitioners. His comparative theology wasn’t driven by novelty but by fidelity—the slow work of letting two traditions speak to him, even confront him, without reducing either. What emerged was a way of being in which encounter doesn’t mean erasure, and fidelity to one’s tradition doesn’t require ignorance of another.

“My comparative theology is my response to a problem,” he writes. That problem is the question of “how to hold two traditions together, when they are being so lovingly learned, without demeaning my own tradition or the newly encountered?” If God is “impossibly nearby, so close as to touch us,” then theology itself must reflect that intimacy—“interreligiously alive and unstable,” revealing the process in motion.

In the end, he describes his work as a grand “act of holding-together”—a way of making sense of who he is and what he has learned, holding in tension what must remain alive in relationship.

For those of us who feel spiritually restless or religiously homeless, who have inherited one tradition but been shaped by several, this book is not just a memoir; it is a map and a mirror. Clooney doesn’t try to blend religions into a spiritual smoothie. He doesn’t reduce them to easy equivalence. Instead, he shows what it looks like to enter a tradition on its own terms, and to allow that encounter to deepen your own.

This is also a book about how we read. In a world shaped by endless distraction, Clooney reminds us that true reading—the kind that transforms—is slow, reverent and contemplative. Whether engaging the Bhagavad Gita, the Gospels or other holy texts, he reads as one being read in return. The text becomes a space of encounter, not a source of easy insight but of formation. This kind of reading is not efficient. But it is powerful. And it is needed, desperately.

Finally, this book is marked by an honest reckoning with the choices we make—and don’t. Every “yes” means a hundred quiet “nos.” Clooney doesn’t dramatize this, but he doesn’t hide it either. He shares that he once dreamed of doing theology while living among the poor, and that it didn’t happen. He recalls seeing a girl crying on the subway—he had the chance to say something, to offer comfort—and didn’t. That was decades ago. Yet she remains in his memory, in his prayers.

Photo: Cover of new book by Fr. Clooney.

He acknowledges that the decision to choose celibacy and religious life also meant giving up another kind of intimacy, another form of love and family. These are not presented as regrets in the self-pitying sense but as part of what it means to live an examined life, one in which you recognize the shape your life has taken and grieve, just a little, the shapes it could not take.

Still, he is clear that the path he chose was the right one—for him—perhaps because it was aligned with that early whisper, the sacred touch that called him to be “only for God” in this specific way: Hindu, Catholic, priest and scholar. That fidelity has been the thread running through it all. And yet the fullness of his account lies not in the resolution of every tension but in his willingness to hold them gently.

Why read this book? Because it reminds us what a life can look like when it flows from a single sacred interruption. Clooney doesn’t offer conclusions. He offers presence. He offers the possibility that your own life, too, might be read as a story of grace.

In the end, this isn’t just a memoir. It’s an invitation.

About the Author:

Father Adam Bucko has been a committed voice in the movement for the renewal of Christian Contemplative Spirituality and the growing New Monastic movement. At the start of his spiritual journey he immersed himself in Yoga and interfaith teachings while living at Satchidananda Ashram–Yogaville in Virginia. He has taught engaged contemplative spirituality in Europe and the United States, and has authored Let Your Heartbreak be Your Guide: Lessons in Engaged Contemplation and co-authored Occupy Spirituality: A Radical Vision for a New Generation, and The New Monasticism: An Interspiritual Manifesto for Contemplative Living.

Father Adam Bucko has been a committed voice in the movement for the renewal of Christian Contemplative Spirituality and the growing New Monastic movement. At the start of his spiritual journey he immersed himself in Yoga and interfaith teachings while living at Satchidananda Ashram–Yogaville in Virginia. He has taught engaged contemplative spirituality in Europe and the United States, and has authored Let Your Heartbreak be Your Guide: Lessons in Engaged Contemplation and co-authored Occupy Spirituality: A Radical Vision for a New Generation, and The New Monasticism: An Interspiritual Manifesto for Contemplative Living.

[This article was reprinted from America: The Jesuit Review]