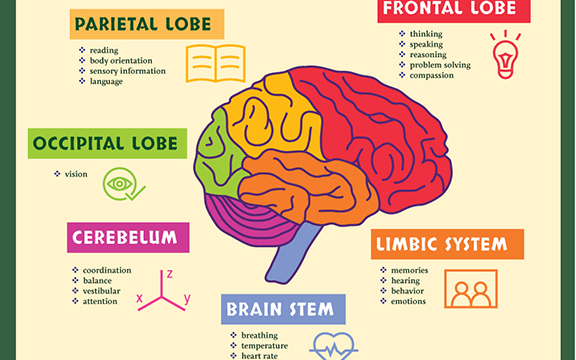

Illustration: The primary functions of the brain

In this penultimate installment of this series on “The Science of Yoga,” Eddie Stern takes us for a further tour of the brain and its relationship with the kleshas, as taught in the Yoga Sutras of Patanjali.

The Limbic System, Raga and Dvesha

The limbic system is in the middle portion of the brain. It is made up of centers that process fear, emotions and memory. Raga and dvesha, our likes and dislikes, attractions and aversions, are both learned and instinctive. Through exposure to environment and the creation of habits that our parents and education introduce us to, we develop habitual tendencies that draw us toward some things and away from others. For example, imagine that one day your parents bring you, as a child, to an amusement park and buy you an ice cream. It’s the best thing you’ve ever tasted. But while you are taking your first bite, your parents wander off and you get lost. The taste of the ice cream and the fear of being lost become linked, and somehow through that trauma, the taste of that one flavor of ice cream always reminds you of being lost in an amusement park when you were five. While some attractions and aversions are learned through experience and exposure, others we are somehow born with, and we do not know where they come from.

Interestingly, the brain’s pleasure centers, the fear centers and the memory centers are all close to each other. Current scientific research on this is extremely complicated and fascinating. Neuroscientists Kent Berridge and Morten Kringelbach examined where “liking” and “disgust” are processed in the brain and published their findings in Neuron Journal in 2015. They discussed how the regions of the brain that are associated with reward-liking, wanting, sensory pleasures, disgust and fear in regard to external stimuli interact with higher-level brain structures such as learning, so that we can actively strategize to move toward pleasure rewards and away from things that disgust us or to which we are averse.

Interestingly, this overlap in neural circuitry with the prefrontal cortex is associated with higher-level pleasures beyond sensory pleasures. The concept of “liking” is associated with the limbic system, and is described as an adaptive response to existence. Our likes and dislikes, even on this neuroscientific level, serve our existence, or our will to live. Abhinivesha is the support of raga and dvesha.

The Frontal Cortex, Asmita and Avidya

That leaves us with asmita and avidya. The cortical region of the brain is the uppermost area. It processes information relating to the executive functions: language, reasoning, strategic planning, pro-social engagement and the expression of compassion, empathy and philosophical contemplation, among other functions. It is in this region of the brain that we can ponder philosophical conundrums such as the distinctions between fate and free will, theodicy, the nature of our conscious and unconscious actions in the world, and the countless other contemplations that philosophers, yogis and seekers have dwelled on for thousands of years. The prefrontal cortex is related to conscious states of awareness, as well as directed states of awareness, while brain stem functions are largely subconscious and automatic. The ability to consciously direct our awareness, which is the basic description of what is happening when we practice Yoga, is a prefrontal cortex operation.

Scientists Christopher Koch and Francis Krick have attempted to identify neural correlates of consciousness, and therefore conscious experience. They propose these correlates are located in the posterior part of the cortex, and that conscious experiences are made sense of, to some degree, in the frontal regions of the cortex, helping to turn the experiencer into the “owner” of that experience. Hence, a story is created by ownership and identity. This is asmita, or I-ness, the narrative we create when we identity the experiences we have as occurring to us. The default mode network, the area of the brain that is active in a restful, waking state, is associated with day dreaming, rumination and, according to the literature presented by Dr. Eva Svoboda, activates when we recall episodic and autobiographical information, self-reflection and semantic processes. Each of these processes is intrinsic to the constructed I-sense that is described as asmita, the first of the kleshas that arises from avidya.

And so what of avidya, the incomplete knowing of who we are? According to Patanjali, it is through the conscious directing of focused awareness and non-engagement with arising memories and thought patterns that we can begin to unravel our misperceptions. We use the power of self-awareness to experience that we are aware. Then that awareness of awareness is a movement inward to places that neuroscience cannot yet describe, but that the yogis have, and in detail. In regard to the brain, this process of consciously directing our awareness towards quiet occurs in the prefrontal cortex.

About the Author:

Eddie Stern is a Yoga instructor and author from New York City. His latest book is One Simple Thing, A New Look at the Science of Yoga and How it Can Change Your Life, and his newest app is “Yoga365, micro-practices for an aware life.” His daily, live Yoga classes can be found on www.eddiestern.com

Eddie Stern is a Yoga instructor and author from New York City. His latest book is One Simple Thing, A New Look at the Science of Yoga and How it Can Change Your Life, and his newest app is “Yoga365, micro-practices for an aware life.” His daily, live Yoga classes can be found on www.eddiestern.com

(Reprinted from Hinduism Today)