According to Dr. Graham Schweig, there is an intimate relationship between the Yoga Sutras and the Bhagavad Gita. With his guidance, our readers are given insight into how to perceive the flowering of the Ashtanga or eight-limbed Raja Yoga system in the Bhagavad Gita.

According to Dr. Graham Schweig, there is an intimate relationship between the Yoga Sutras and the Bhagavad Gita. With his guidance, our readers are given insight into how to perceive the flowering of the Ashtanga or eight-limbed Raja Yoga system in the Bhagavad Gita.

Integral Yoga Magazine (IYM): Sri Swami Satchidananda said that the easiest way to control the mind was to dedicate one’s actions. This would seem to be the Bhakti Yoga philosophy of both the Gita and the Sutras.

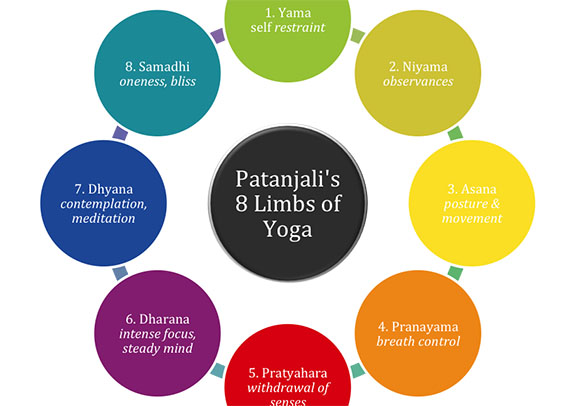

Graham Schweig (GS): Absolutely. Both Lord Krishna and Sri Patanjali show us that the sense of ahamkara, the notion of “I am acting alone” and mamatva, “mine,” the feeling of possessiveness, are to be transcended. Our sadhana (spiritual practice) enables us to prepare the way of the heart. Ultimately the perfection of our spiritual path is to act out of love. We become instruments of love, detached from both our actions and the result or fruits of those actions when our hearts are fixed on the Divine. As long as we see that we are ultimately dependent upon the divine for everything, then we can begin to see our relationship with the Divine and begin to know, connect to and embrace the Divine. The eight limbs of Raja Yoga prepare the way of love, if one knows to look for it. It is the flowering of the Ashtanga Yoga path into the renunciation and devotion illuminated in the Bhagavad Gita. The path of liberation is to free ourselves from the ahamkara of the Gita, and the avidya and asmita of the Sutras.

IYM: Is there one particular sutra that speaks to the heart (pun intended!) of a Bhakti Yoga and Raja Yoga connection in the Sutras?

GS: This connection is most immediately described in sutra 3.2, which says that dhyana is the one-pointed continuous movement of the mind toward a single object. The eight limbs of the Ashtanga system are most deeply expressive of the eight constituent and simultaneous processes of the heart in love—the heart that has given itself fully to the Divine.

IYM: So, from this perspective, the flowering of bhakti on the Raja Yoga path would be the focus of the mind on the Beloved?

GS: A goal of our Yoga practice is to cultivate the flow of thought to a single object. What one point, what singular object could possibly command our attention 24/7? What if the one point we focused upon—with thought constantly flowing toward it—contained everything in the universe? That would mean anything we are focusing on—even eating breakfast, tying our shoe lace, driving to work—would be fixed in meditation on that point. What would that one point be—to command the loyal dedication of our hearts, sleeping or waking, all the time? Such an object must have a great power to be able to command the attention of both our minds and hearts. That ultimate object of meditation is Ishvara, that supreme point within which everything is contained. In the case of the Gita, Ishvara is Lord Krishna. Patanjali instructs us to choose our Ishta Devata—the Divine Beloved. There is no better way to focus the mind than to concentrate on what you love. The mind is outdone by the heart in its ability to be fully absorbed.

IYM: Are the Gita and the Sutras telling us there is no need to progress through all the eight limbs if we can have that focus on the Divine Beloved?

GS: The eight limbs of Raja Yoga are considered hierarchical in one sense and, in another sense, they are all constituent to Yoga and equally important. So, all the limbs must be functioning at the same time. There is a distinction to be made between the practice of each limb (sadhana) and the accomplishment (siddhi) of each limb. Patanjali conveniently couches the processes of Yoga in a way that allows practitioners to apply these limbs at whatever level, whatever stage they are. Beyond the practice of each limb, is its perfection. The siddhis of these limbs are only revealed to the hearts of practitioners ready to receive them. What the Gita is talking about is the siddhi level, the state of perfection within the eight limbs. These eight limbs, in effect, become limbs of the heart for achieving Ishvara pranidhana (worship of one’s loved divinity), ultimately. Consider this: Just as Ishvara embraces souls with His various manifestations, the yogi can embrace the Lord with the eight limbs of the heart. (include this there is room)

IYM: Where in the Gita can we find the various Raja Yoga limbs?

GS: The Gita, throughout its teachings, exemplifies and speaks about all eight limbs. Yama (the first limb) consists of five ethical principles. Ethical expectations such as nonviolence, truthfulness and so on, are also described in the Gita through numerous verses describing a person possessing the highest ethical values. Niyama (the second limb) consists of the things we should practice or observe. This includes Ishvara pranidhana, which is central to the Gita—a scripture that is essentially a “gita,” a song of divine love and worship. The Gita is filled with verses in which Krishna is urging Arjuna (the Atma or soul in the form of Arjuna) to be dedicated to Him.

IYM: What about the third limb, asana?

GS: In the Gita, Arjuna asks Lord Krishna to describe how to recognize a realized soul. Arjuna asks questions about how a realized soul would stand or sit, how the person of steady wisdom walks, how that person situates the body. So, we see that even Arjuna is interested in the way the body is positioned—not just in asanas in the formal hatha sense, but how one controls the movements of one’s limbs. Meditative discipline of the body is discussed very fully in the Gita, when describing how to put the body in an asana position with spine erect, the gaze fixed between the eyes, and so on. In divine love, however, every position of the body expresses devotion.

Pranayama, the fourth limb, is represented in the Gita. There are some beautiful verses in which Krishna talks about offering not only the incoming and outgoing breath to each other, but about dedicating one’s own life breath to the Divine. Krishna says, “Have your prana come to Me.” When one offers every breath with love, what need is there for trying to manipulate the life breath? One breathes in the love one receives and when one breathes out, it is an offering to the Divine. It’s the breath of the heart. This points to the mystical underpinnings of pranayama practice.

IYM: And, what about pratyahara (withdrawal of the senses), the fifth limb?

GS: In the second chapter of the Gita, there is an instruction to Arjuna to be like “the tortoise who withdraws its limbs within its shell.” The teaching in the Sutras and in the Gita goes deeper than the idea that the yogi withdraws from the senses or the world entirely. Rather, the teaching is to learn to withdraw one’s attachment and preoccupation with sense objects. One of the easiest ways to cultivate this detachment is through the practice of Bhakti Yoga. As Swami Satchidananda often said, the simple formula is to turn mine into Thine.

This is the Bhakti Yoga teaching found in the Sutras and the Gita. If one really knows the form of the Divine Beloved, everything else pales by comparison. With love there is automatic renunciation from all else. That is what it means to be attracted to the Beloved. The siddhi or Ishvara pranidhana of pratyahara is to focus all the senses on the beautiful, intimate form of the Lord. We can practice all day long. We can struggle to withdraw our senses from the delicious chocolate cake calling out to us from the window of a bakery. But, we don’t have to fight with our senses, if we offer them in service. Through these scriptures, we learn to engage the senses in the service of the Divine Lord, the Master of the senses. Pratyahara siddhi, the perfection of this practice, is when rather than focusing on “melt in your mouth” chocolate, you melt at the vision of the Divine. There is no need to withdraw the senses, as long as you understand to whom the sense objects and everything belong.

IYM: What about the last three limbs of Raja Yoga: dharana, dhyana, samadhi?

GS: These three limbs comprise samyama which means, the perfect discipline or perfect practice. These three upper limbs are where one actually focuses. They are where one first encounters the Beloved object. You might call it the “meeting stage.” One suddenly turns one’s complete attention to the beloved object because one is just encountering the Beloved anew. In theses first encounters there may be interruptions. So, we want to continually return to the object, bringing the mind back to this focal point. In the Gita, Lord Krishna states, “If you can’t be fully absorbed in Me, you can do something else that will help you concentrate.” As dharana develops, we find that it’s not merely by our own effort that we can concentrate, but it is the very power of the object drawing us to itself. When that object is so beautiful and beloved, the object itself commands our hearts.

Once we discover Ishvara pranidhana, it is no longer just by our own effort that we are able to concentrate. There must be effort on our part, but we are not alone—the power of the divine object itself attracts itself to us. Then our dharana sadhana doesn’t become a chore or exercise, but it commands our attention. Once that attention is undistracted and uninterrupted—because we come to know the beloved more and more—we are so in love and then there is uninterrupted flow, which is called dhyana (meditation). We cannot take our minds and hearts off the object. This can be achieved by an act of will but, if it is dhyana siddhi, it is then that the mind and heart are endlessly and continuously sustained by and absorbed in the beloved object. There can be no better way to concentrate or meditate then on the natural affection of the heart for the Supreme Beloved.

IYM: It seems easier to grasp the concepts of concentration and meditation, than it is to understand the experience of samadhi.

GS: Samadhi is considered the ultimate perfection. As we progress from one limb to another, the more perfected each of the limbs become. One never leaves any of the steps, however, one just delves more deeply into each. Samadhi means, “to place over completely.” It is a complete spilling over of the Self into the object of meditation to the point where Patanjali says in sutra 3.3 that samadhi is the appearance of only that particular object—as if our own intrinsic nature is empty. It is the state of perfect and total absorption. This is the shunya of Buddhism—the meditator considers or treats him or herself as if he or she no longer exists; his or her existence is voided because the meditator is utterly and totally absorbed in the object of meditation. It is the heart that knows best that experience of samadhi.

IYM: In a sense, the very concept of samadhi seems almost more Buddhist or Vedantic than devotional. How do you make that devotional connection?

GS: The proof may be found in sutra 2.45: “Samadhi Siddhir Isvarapranidhanat.” Here Patanjali says that the perfection of meditation is dedication to the Supreme Lord. So, as early as in the second limb, Patanjali gives us the perfection of the perfection—the perfection of the eighth and final limb. We can see how the limbs are integrated, not merely hierarchical. Patanjali did this deliberately. Ultimately, Yoga is the mutual embrace of the human soul (Atma) with the Supreme Soul (Purusha). Is there any better way to understand samadhi than to understand how love completely models the perfect samadhi? One goes so deep into meditation that one loses oneself in the focus on a single object and experiences the shunya. We become emptied of any sense of any intrinsic nature—we don’t even know we exist. There is only the object upon which we are focusing. There is a total emptying of oneself and, effectively, a filling oneself up with the object. This is the best definition of love—when one is so clear-hearted, the heart is no longer troubled. There no longer are any coverings, kleshas or obstructions. The mind is so clear and purified that it can afford to forget itself. One no longer needs to be self-centered or self-concerned. One no longer needs a self! Metaphysically the self always exists, but the self offers itself utterly to the Beloved. That is the self-surrender of love.

About Graham M. Schweig, PhD

Dr. Graham Schweig received his doctorate in Comparative Religion from Harvard University, and is a specialist in the philosophy and history of Yoga, bhakti devotional traditions of India, and love mysticism in world religions. He is currently Associate Professor of Religious Studies and Director of the Indic Studies Program at Christopher Newport University. He is the author of numerous articles and books including, Dance of Divine Love and Bhagavad Gita: The Beloved Lord’s Secret Love Song. For more information, please visit his website: secretyoga.com.