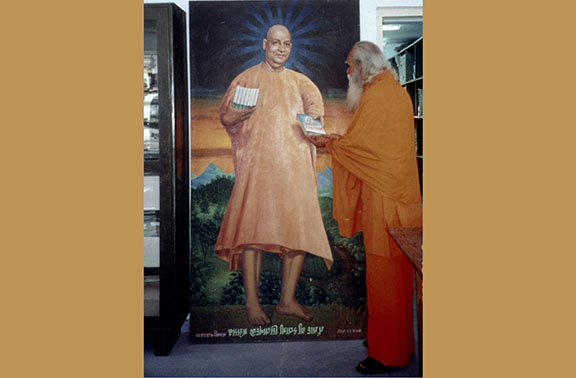

Swami Satchidananda demonstrates how Swami Sivananda was “Give-ananda.”

At one time, there were four great holy sages who were living in different parts of India. They must have had some sort of communication between themselves because they all said goodbye, one after the other, within the same period.

Swami Ramdas, who was a great Bhakti Yogi, was completely devoted. He lived a life of total surrender to God. Sage Ramana of Tiruvannamalai demonstrated the Vedantic approach of Jnana Yoga. He spoke very little, but whenever he said anything, it was about the knowledge of one’s own true Self. If anybody asked him a question, he replied, “Who is that asking the question?” If the person said, “It’s me,” he would ask, “Who is ‘me’? Find out.” His questions were to make you think. The scriptures call that direct approach, Vihanga Marga. That means, like a bird that flies straight to the fruit and catches it. Another great saint, Sri Aurobindo, was more or less a Raja Yogi; he was very scientific, analyzing everything. And then, there was Sri Swami Sivanandaji.

Each of the first three were mainly emphasizing one of three areas: Bhakti Yoga, Raja Yoga, or Jnana Yoga. Only in Gurudev Sivanandaji did you see it all, a combination of everything, and that’s why his approach is called Poorna Yoga. He integrated the various branches of Yoga. One cannot be always a bhakti, or always be a jnani, constantly meditating. We all have various aspects to our lives. If you’re only a Raja Yoga meditator, after the meditation what would you be doing? Who are you? What are you then? If you are a Bhakti Yogi only when you do some puja or worship, then when you go to the office, you are just an ordinary person. So why not inject this inspiration into every minute of your life, whatever you do, no matter what you are?

The Sanskrit word for Integral Yoga would be Sampoorna Yoga—complete in itself. Whatever you do is done in a yogic way. That is the greatness of Swami Sivananda. He had a complete combination, a beautiful balance of everything. And that is the reason why he was able to attract people from all over the globe. In fact, he never went out of India except for the three days he went to Ceylon, now known as Sri Lanka. In the year 1950, he had a sort of two-month tour throughout India and three days was scheduled for Ceylon.

But, people from all over the world came to him. Sitting in one place, he attracted many thousands. Only he could do that because his teachings are very simple; there’s no words of learned length and thundering sound. Any child could understand his language. His books are that simple. They are talking to you directly. Sometimes, the people who edited his words would say, “Swamiji, this whole thing has already been said in the previous chapter.” He’d reply, “Don’t worry, say it again and again, there’s nothing else new.” So, to have a big book, there would be a lot of repetitions. He would say, “Well if you read it ten times, someday, one of those times, it will really go into your brain!”

He wrote more than 350 books on all subjects. He was an average writer and used simple language. That’s why his books are read by everybody. In a way, he forced so many to read. How? By sending books to everyone! Our postage expenses suddenly had gone quite high from mailing books. I was in Ceylon at the time, and I said, “Gurudev, you sent a lot of books to the Prime Minister of Ceylon; he’s a Singhalese man and he’s a Buddhist, so whenever he sees the books he says, ‘Okay, put it over there.’ He’s never read even one of the books!” Gurudev would reply, “Somebody would have read it, it is not?” Somebody would have read it, very true. Knowing fully well that one person was not reading his book he would still send it because he knew that nobody is going to throw it out. If he doesn’t read it, somebody else will.

When he was healthy and the body was allowing him to come to the office, he would ask, “What is today’s cake?” Not the eating cake; he would expect something from the printing press to be sitting there on the table. “Hot, hot cake,” he would say. It can be just small leaflets or heavy, big books. Immediately he would say to people there, “Take this, take this.” He was always promoting, and propagating millions of small leaflets on various subjects.

But of course there is another secret also. Most of the books were printed from donations. He would ask the donor to write their biographical information and he would put that and their picture in the book or leaflet, along with his own picture. Many people printed books just for that. He would say, “It doesn’t matter; if that’s what they want, then give it to them. All this can feed the rest.” Every time we went out, he would ask us to carry hundreds and thousands of leaflets. “Go, give it to whomsoever you see, just give it. Anyone going to the train? Then give it to the passengers. Just leave them in the compartment and go. When someone gets up, he will take it with him and read it.”

Very often we would even joke with Swamiji. “Gurudev, what is this that you are printing? You spend so much money, look what happened to our leaflets. That fellow that was sitting here has his food wrapped in one!” Once he told us, “You know, the other day somebody came here and you know what he told me?” ‘I bought some food, I was eating it, I finished it, and then I casually opened the paper it was wrapped in. It was a paper with spiritual instructions.’ He read it and now he has come here to the ashram.”

That was his way of making people aware of the spiritual truths. Nobody has ever promoted things like this. Apart from teaching Bhakti Yoga and Vedanta, he was unique in that he put so much emphasis on Hatha Yoga. Many western countries learned Hatha Yoga because of him. He was a pioneer.

And with all that, you can call him a good comedian also. He was always jovial. It is impossible to fathom him, who he was. One day, he was wearing a nice shawl that somebody gave him. An ashramite who had none, came along. Gurudev said, “Come on take this, use it” and he gave it to him. Then, after a month or so the person who sent the shawl was visiting the Ashram. Gurudev said to me, “Oh no, he would be happy if he sees me wearing the shawl but I gave it away. I don’t know how to go and ask him for it back. Will you go and get for me? Just borrow it from him until that guy comes and goes away, and then give it back.” How conscious he is about all of this. He wore many things so that when people came to the ashram they would be happy to see he was wearing what they gave.

I used to go to the Ganges to meditate, very early in the morning, or sometimes, very late in the evening, after everyone had gone away. I would sit for a long meditation. One day, I heard Gurudev literally shouting at me. He just came from behind me. “Oji, what are you doing?” He always called me “Oji.” It’s a sort of respectful term that simply means, “Hey, sir, hey mister—like that. Oji. So, he asked me, “Oji, what is this nonsense?” I replied, “I’m just meditating.” “Oh, I see. Aha. You see the temperature now? It‘s a little chilly. What do you want to have, meditation or lumbago? I have lumbago because I used to go and stand in the Ganges water, waist deep and meditate. You don’t need to do that. They may have done it long before and put it in the books, but our bodies and bones are not strong enough these days so don’t go to extremes.”

Wherever he was, he would literally be watching. Particularly, when you are sincere, you would get his help directly or indirectly. A young boy came and he was playing the Temple harmonium terribly. He was the son of a very well-known musician and actor. Gurudev came and said, “Oh, look at that: as the father, so the son!” But we all had to close our ears! Gurudev was simply appreciating it, “Oh, wonderful, play one more, play one more. Bring all the music books and give to him.” He was given food, gifts and a title, Sangita Joyti, the Light of Music. We never knew what was happening behind all this. When the boy came the following year, he was a harmonium expert. This inspiration from Gurudev made him go deep into that and he became a real musician.

Gurudev had several different address lists: one for prime ministers, one for presidents, others for politicians, doctors. Certain books were good for certain people and we would send them whether they knew of Gurudev or not. There was one peculiar list, a list of misers. They would also be sent books even though they would never even send ten dollars. We would complain to Gurudev saying, “You are sending him hundreds and hundreds rupees worth!” Gurudev would tell us, “Somebody is giving me, somebody is getting; it doesn’t matter. Who knows? One day he will be tired of being a miser. He’ll get tired of receiving books again and again. All of a sudden his mind will change and he may do something. It doesn’t matter; you don’t expect anything, you just send.” I have never seen anybody giving, giving, giving and giving, giving, giving like that. That’s why he wasn’t known as Sivananda but he was known very much as “Give‑ananda.”

When I first saw him, I was rather full of myself and he knew it. As soon as he saw me, he said, “Ah, the Madrasa (a person from Madras). Madrasa, ah. Vanga, vanga, vanga, come, come, come. Ah, you have come to see me? Aha, okay, have some coffee, we’ll talk afterwards.” He said, “You’re from Madras, you are used to coffee, so why worry? Just come, have a cup of coffee.” If you are from Madras, it is impossible to go without coffee! Afterward, we were talking and he asked, “Ah, okay, now tell me a little about you.”

“Just nothing to say, I’m just a humble seeker, moving around and I heard of you.”

“Oh, you have heard about me? So you have come to me. What do you think about me?”

And I had the audacity to tell him, “Swamiji, I was a little disappointed.”

“Huh? Huh? Huh? Disappointed with me? Why? What is the problem?”

“Having heard a lot about you, as the greatest Maharishi in the Himalayas, I came to see you and I expected you to sit in a big throne, meditating. Then, I had to wait for half an hour before you came out. And you were playing, running around, making me drink coffee and joking.”

“Oh, I see. You are disappointed. I am sorry.” Then he started immediately acting like a rishi.

“Well there you are, am I all right now?”

And I said, “Now I like the other one.”

“Ah, so I can be the same old person again? What do you do? Do you do a little Yoga?”

“Yes sir, I used to practice a little Hatha Yoga. I learned from books in South India.”

“Ah, good, all right, you will be in charge of my Hatha Yoga department.” Right away, he put me in charge! Within a few minutes, I had been promoted to Raja Yoga professorship. And I had been given the title, Yogiraj. For some time I was very proud, and I would never leave anywhere without using it in my name. Everybody would know Yogiraj Swami Satchidananda! That’s how he lifted people up, inspired them. His ways were totally different, unique. Nobody ever lived like that and I don’t think anybody is now. He is the only one, there is only one Sivananda.

In a way we were very, very fortunate in being with him, getting blessed by him. Even in a regular satsang he would ask others to talk. He would get the Indians to sing some bhajans or one or two verses. But once he began to talk, he’d be roaring like a lion, “Oh immortal Self, Atman, blessed souls!” His tone, itself, was very different at that time. At other times, on the road, on the Ganges banks, or somewhere in the work area, as soon he met someone he would immediately stop and say a few words: do this, do that, this is the correct way. That is how he taught. Never in a regular classroom, though we did have the first Yoga Vedanta Forest University. He made all of us professors. The University was very, very, very simple. But his blessings itself were enough.

And he is still continuing to take care of us all. His presence is here; he’s so thrilled at seeing you all. We were simple ordinary folks and he led us into big things. His disciples are all over the world now. Chidanandaji is continuously traveling. Venkatesanandaji also traveled around. He created many well-known students: Vishnudevanandaji, Jyotirmayanandaji, Sivapremananadaji. Though he never went out of the ashram much, he created people to go around and spread the message. So, in a way, we are so fortunate even to think of him, and to celebrate his birthday and to get to know a little bit of his simple teaching.

His teachings are very simple, and being a doctor, he believed in tablets! So the teachings are tablet-like: “Serve, Love, Meditate, Realize.” And even if this is too much, just, “Be good and do good.” That’s all. What do you teach on Sundays? Be good, do good, finished. All the teachings of all the religions are summarized in this same way: be good, do good. First you be good, and then, if you are good, you will certainly do good also. Merely being good is not enough; you are to be doing something otherwise you are good, but no use to anybody.

He taught, “Adapt, adjust, accommodate.” Wherever you are, it doesn’t matter, adapt yourself. Because if you train your mind to accommodate everything, you get the benefit. You should not allow your mind to blame others. You should tell your mind to face it, learn something from that, and see the nice thing in that, the good thing in it. Then there is personal training or self‑reformation. And the biggest practice, which is the highest sadhana, is to “bear insult, bear injury.” If somebody injures you, accept it, insults you, accept it. How simple his teachings are!

He put so much emphasis on living Yoga. Let every action, every thought, every word be permeated with the spirit of Yoga. So, you’ll be really celebrating this Jayanthi by imbibing at least a few simple instructions that are given to us by him, to make our life a little richer in the spiritual field. That way we are able to celebrate the Jayanthi usefully.

He doesn’t need all this glorification. He wants us to grow and to be like him. So let us wish and pray that we become good recipients; not to pray for him to bless us, he is already blessing us. We should become good recipients; we should become good receivers. So that is the humble request that should come from our hearts to that great, holy master. Thank you. God bless you. Om Shanti, Shanti, Shanti.

(Transcribed & edited by Reverend Bharati Gardino)