Rev. Jaganath, Integral Yoga Minister and Raja Yoga master teacher, has spent a lifetime delving into the deepest layers of meaning in Patanjali’s words within the Yoga Sutras. Our series continues with sutras: 2.6 through 2.8. Here, Patanjali elucidates further on the second, third, and fourth of the five klesas, the causes of our human suffering. The parallels to Buddhist thought are particularly reflected in Patanjali’s discussion of attachment (desire, clinging) and aversion.

Rev. Jaganath, Integral Yoga Minister and Raja Yoga master teacher, has spent a lifetime delving into the deepest layers of meaning in Patanjali’s words within the Yoga Sutras. Our series continues with sutras: 2.6 through 2.8. Here, Patanjali elucidates further on the second, third, and fourth of the five klesas, the causes of our human suffering. The parallels to Buddhist thought are particularly reflected in Patanjali’s discussion of attachment (desire, clinging) and aversion.

Sutra 2.6. dṛg-darśana-śaktyor eka ātmatā iva asmitā

Egoism is the identification, as it were, of the power of the Seer (Purusha) with that of the instrument of seeing [body-mind] (Swami Satchidananda translation). Egoism arises from confusion, regarding the power of the Seer and the power of the instrument of seeing (mind/intellect) as the same thing (Rev. Jaganath translation).

Doesn’t the Bible say “Blessed are the pure in the heart, they shall see God?” When? Only when there is purity in the heart; a heart peaceful and free from egoism–the “I” and the “mine.” Purity of heart and equanimity of mind are the very essence of Yoga. —Sri Swami Satchidananda

dṛg = seer; discerning (See 2.20)

from dṛś = to see perceive

darśana = instrument of seeing; what is seen, philosophy, view, knowing, exhibiting, showing, looking at, teaching, seeing, perception, way of looking, apprehension, observation, aspect, act of seeing, inspection, contemplating, vision (See 1.30, 2.6, 2.41, 3.32)

from dṛś = to see, perceive

Refer to 1.30 for more on darsana.

śaktyor = powers; ability

from śak = to be able

Shakti is the term for power. It is especially associated with the force within and behind creation. All movement, all force, all power, is an expression of shakti. It is regarded as feminine and often depicted as a goddess.

In Hinduism, even the gods are depicted as needing shakti which is why Hindu gods are associated with goddess consorts, their shakti. Without this feminine energy, the god is powerless. This imagery is a way to depict the natures of Purusha (pure consciousness, but without agency) and prakriti (matter and change). When viewed as the latent force of evolution within every individual, it is referred to as kundalini shakti, the coiled force that rests at the base of the spine in the subtle body.

In this sutra, shakti is in the dual tense, referring to two powers – the power of the Seer and the power of the seen.

eka = identical; the same, one, alone, solitary, single, one and the same, singular

ātmatā = selfness; nature, essence

from ātma = self + tā = a suffix meaning having the quality of, of a single self

This refers to the ego’s ability to cause a fundamental confusion of self- identity by assigning the power of consciousness (atmata, selfness) to the body/mind.

iva = as; as if, as it were

asmitā = egoism; I-am-ness, sense of individuality, the sense of ‘I’ before it takes on identifications (See 1.17, 2.3, 2.6, 4.4)

from as = to be + tā, a suffix suggesting to have the quality of

Refer to sutra 2.3 for more on asmita.

Sutra 2.7 sukha-anuśayī rāgah

Attachment is that which follows identification with pleasurable experiences (Swami Satchidananda translation). Attachment arises from clinging to pleasurable experiences (Rev. Jaganath translation).

sukha = pleasurable

Pleasure in spiritual contexts is understood as enjoyable experiences that are temporary. Pleasure, as nice as it is, should not be mistaken for true happiness which is an uncreated experience. We often substitute the words joy or bliss to differentiate this experience from happiness. Pleasure is called a created form of happiness because it requires the convergence of a desire with its object. Take away either of the factors needed to experience it and it falls apart, often becoming some form of dissatisfaction or suffering (duhkha).

True happiness arises independent of external and mental circumstances. It is the light of the Self, shining unhindered on the mind – unobstructed by attachment and ignorance. It cannot be created; any external force also cannot destroy it. It is uncreated joy. It exists and persists in us as our True Nature.

anuśayī = clinging to; resting on, follows.

from anu = along, after + śaya, from the root śi = to rest

After resting with, could be a literal translation for anusayi. It is used to denote the close connection between an act and its consequences. It is also used to refer to the cause of rebirth.

In Buddhism, anusayi means tendencies or passions that lay dormant, a fitting notion when considering that often the pain-bearing nature of attachments is not realized immediately, but only when the object of attachment is lost to us.

The most important point here is to note that clinging is out of step with the nature of life, which is constant change. We cling when we feel and fear change. To cling is to resist life. It is to hold onto hopes, images, and a limited understanding of self and life. Many of life’s lessons and beauties are missed when we cling.

Pleasurable experiences depend on circumstances that inevitably change, and the nature of most change involves some degree or type of loss. And with the loss of whatever brought us pleasure, the pleasure itself leaves. The fear of loss leads to the clinging to the pleasurable experiences mentioned in this sutra.

The yogic attitude is to enjoy pleasurable things when they arrive and peacefully send them off when it is time for them to move on. Enjoy the beauty of a sunset while it lasts, but don’t ask for or hope that the sun won’t drop below the horizon. Let the mind enjoy the flow of life. Let the joys of life – large and small – nourish your mind and soul. Clinging to them is not the best strategy for happiness.

The happiness that arises when the mind is peaceful, clear, and one-pointed is a deep happiness, but it is still a facsimile of the unbounded, eternal happiness of the Self. It is the happiness of the Self or Seer reflected on a sattvic mind. To attain the highest enlightened state, attachment to even this rarefied happiness needs to be transcended.

The Bhagavad Gita, 14:6, on this subject: Although the sattva guna is pure, luminous, and without obstructions, still it binds you by giving rise to happiness and knowledge to which the mind readily becomes attached.

rāgah = attachment (See 1.37)

The subject of attachment is central to any discussion of the theory and practices of Yoga. Ignorance, the source of all the other klesas, is difficult to identify directly. Attachment, aversion, and clinging to bodily life are more easily perceived and therefore more readily addressed.

The nature of attachment includes:

- Craving for pleasure based on sense satisfaction

- Loss of perspective and objectivity

- The expectation that what does bring satisfaction will never change

- The conviction that some object or situation is absolutely necessary for happiness; the search for happiness in externals

Sutra 2.8 duḥkha anuśayī dveśaḥ

Aversion is that which follows identification with painful experiences (Swami Satchidananda translation). Aversion arises from clinging to painful experiences (Rev. Jaganath translation).

duḥkha = painful; dissatisfaction

Recall that duhkha is a pervasive, persistent feeling of precariousness. This is fertile ground for fears to grow. (Refer to 1.31 for more on duḥkha.)

anuśayī = clinging to; resting on, follows (See 2.7)

dveśaḥ = aversion; hatred, dislike, repugnance, enmity to, distaste (See 2.3, 2.8)

from dviś = foe, enemy

No one spends their lives seeking painful experiences, but this sutra is not about the painful situations themselves. It is about aversion to them.

The original meaning of the English word, aversion, can give us an insight into why it works against our intentions and efforts in Yoga: to turn away or avert one’s eyes. When we close ourselves off or back away from inevitable challenges and hardships – a major part of life experiences – we are in danger of losing the opportunities to learn and grow from them. A state of aversion brings with it anxiety. But, anxiety does not have to be understood as a form of fear.

Anxiety is from a root that means narrowness or tightness. Anxiety results from being in a difficult situation, one that demands courage, faith, creativity, or persistence to move through. Situations that feel tight, trapped, and with few, if any options, are part of the challenges we face in life. But, our response to anxiety need not necessarily include fear. By understanding this, by eliminating anxiety-producing situations from the list of fears, we free the mind of a great burden. We experience less threat and more challenge. We are more likely to perceive the challenge accurately and call on our creative impulses to resolve the problem and summon our faith to endure it with tranquility.

Fear, on the other hand, is a type of mental paralysis. It is always a reaction against a possible future loss. It is a mind taken out of the present and instead contemplates what dire, painful consequences may be coming our way. Fear feeds imaginary fates. Faith is the best antidote for both fear and anxiety.

The word for faith in Sanskrit is shraddha, literally to hold in a pure heart. Through Yoga, we learn to have increasing trust in the ways and wisdom of life. When we are in a tight spot, we pause, collect ourselves and return to our clear center. Often, creative options begin to arise.

Faith is a bird that sings when the dawn is still dark. —Rabindranath Tagore

Faith is taking the first step even when you don’t see the whole staircase. —Martin Luther King, Jr.

Faith is the strength by which a shattered world shall emerge into the light. —Helen Keller

The same equanimity we have learned to apply to nonvirtuous situations can be used here. (See 1.33)

About the Author:

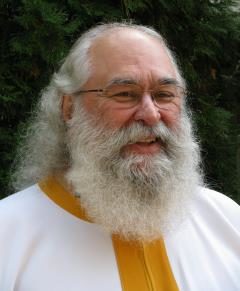

Reverend Jaganath Carrera is and Integral Yoga Minister and the founder/spiritual head of Yoga Life Society. He is a direct disciple of world renowned Yoga master and leader in the interfaith movement, Sri Swami Satchidananda—the founder and spiritual guide of Satchidananda Ashram–Yogaville and Integral Yoga International. Rev. Jaganath has taught at universities, prisons, Yoga centers, and interfaith programs both in the USA and abroad. He was a principal instructor of both Hatha and Raja Yoga for the Integral Yoga Teacher Training Certification Programs for over twenty years and co-wrote the training manual used for that course. He established the Integral Yoga Ministry and developed the highly regarded Integral Yoga Meditation and Raja Yoga Teacher Training Certification programs. He served for eight years as chief administrator of Satchidananda Ashram–Yogaville and founded the Integral Yoga Institute of New Brunswick, NJ. He is also a spiritual advisor and visiting lecturer on Hinduism for the One Spirit Seminary in New York City. Reverend Jaganath is the author of Inside the Yoga Sutras: A Sourcebook for the Study and Practice of Patanjali’s Yoga Sutras, published by Integral Yoga Publications. His latest book, Patanjali’s Words, is coming soon from Integral Yoga Publications.

Reverend Jaganath Carrera is and Integral Yoga Minister and the founder/spiritual head of Yoga Life Society. He is a direct disciple of world renowned Yoga master and leader in the interfaith movement, Sri Swami Satchidananda—the founder and spiritual guide of Satchidananda Ashram–Yogaville and Integral Yoga International. Rev. Jaganath has taught at universities, prisons, Yoga centers, and interfaith programs both in the USA and abroad. He was a principal instructor of both Hatha and Raja Yoga for the Integral Yoga Teacher Training Certification Programs for over twenty years and co-wrote the training manual used for that course. He established the Integral Yoga Ministry and developed the highly regarded Integral Yoga Meditation and Raja Yoga Teacher Training Certification programs. He served for eight years as chief administrator of Satchidananda Ashram–Yogaville and founded the Integral Yoga Institute of New Brunswick, NJ. He is also a spiritual advisor and visiting lecturer on Hinduism for the One Spirit Seminary in New York City. Reverend Jaganath is the author of Inside the Yoga Sutras: A Sourcebook for the Study and Practice of Patanjali’s Yoga Sutras, published by Integral Yoga Publications. His latest book, Patanjali’s Words, is coming soon from Integral Yoga Publications.