Rev. Jaganath, Integral Yoga Minister and Raja Yoga master teacher, has spent a lifetime delving into the deepest layers of meaning in Patanjali’s words within the Yoga Sutras. Our series continues with the 24th sutra of Chapter 1 in which Patanjali goes on to further describe the qualities of “īśvara.” Also, in this sutra Patanjali first addresses the concept of the klesas, the root cause of suffering, according to Yoga philosophy.

Rev. Jaganath, Integral Yoga Minister and Raja Yoga master teacher, has spent a lifetime delving into the deepest layers of meaning in Patanjali’s words within the Yoga Sutras. Our series continues with the 24th sutra of Chapter 1 in which Patanjali goes on to further describe the qualities of “īśvara.” Also, in this sutra Patanjali first addresses the concept of the klesas, the root cause of suffering, according to Yoga philosophy.

Sutra 1.24 kleśa-karma-vipāka-āśayair aparāmṛṣṭaḥ puruṣa-viśeṣa īśvara

Isvara is the supreme Purusha, unaffected by any afflictions, actions, fruits of actions or by any inner impressions of desires (Swami Satchidananda translation). Ishvara is a unique Purusha. It is never touched by the root causes of suffering (klesas), the entanglements created by actions, their reactions (karma), and the subconscious impressions (samskaras) produced by these actions (Rev. Jaganath translation).

kleśa = root causes of suffering; pain, affliction, distress, pain from disease, anguish, wrath, anger, worldly occupation, care, trouble

from kliś = to be troubled, to suffer distress

In some Hindu scriptures, the klesas are referred to as viparaya, error or misperception. This is because the root of the klesas is ignorance of our true nature, the Seer. All suffering (duhkha) stems from this basic misperception of self as Self. (see sutra 1.8)

Ignorance (avidya) is common to all human beings until liberation (kaivalya). This is much like what Christians refer to as original sin, which all human beings bring with them at birth. Why this is so, no one can give an answer that satisfies the intellect. The great faith traditions accept spiritual ignorance (not knowing the Self) as a fact of human existence and instead focus on ways to become free of it and the suffering it brings in its wake.

In Buddhism, the klesas are considered to be the properties that dull the mind’s perceptive abilities. They are the cause of all non-virtue and suffering. As in the Sutras, the klesas are also the cause of rebirth. All the klesas are eliminated by the attainment of pure insight. Meditation is stated as the practice that gradually evaporates the klesas. (See sutra 2.3 where the five klesas are listed: ignorance, egoism, attachment, aversion, and clinging to bodily life.)

karma = actions; performance, business, special duty, occupation, obligation, any religious act or rite (especially with the hope of future recompense and as opposed to speculative religion or knowledge of spirit), product, result, effect, fate (as the certain consequence of acts in a previous birth)

from kṛ = to do, act, or make

In the West, we know karma as the universal law of cause and effect; we reap what we sow. However, the same word has an older meaning. Karma was used to designate the acts performed during rituals. Later, the Upanishads (fundamental scriptures discussing principles of Advaita Vedanta) expanded the understanding of karma to include any act performed by a human being.

Karma as action and reaction and karma as ritual acts have an important principle in common. Both present the power of human actions—not the powers of gods or other celestial beings—to determine destiny. The person who engaged in ritual acts expected rewards to come from their ritual sacrifices. It was believed that ritual could control the gods. In this way, rites performed perfectly, according to sacred tradition, were believed to determine one’s future. The law of karma, as we know it now, is the final stage in the development of the understanding of karma as the power to create, change, and determine how destiny is determined.

India’s Historical Development of Karma

Over, time, Indian philosophy’s interpretation of karma evolved. At the start, all power lies with the gods who control everything. Ritual (sacrifice, yajna) is a way to appease or please them to attain what is needed and desired. Religious rituals and rites have the power to control or influence the gods. The power to create destiny rests in individuals themselves. Here is where karma and free will meet. This last stage leads to the next rather large leap of understanding: For the mystic or yogi, the ultimate sacrifice or rite is not something performed at a temple, or altar, or by a priest, but is the sacrifice of ignorance and selfish attachments at the altar of wisdom.

Reflecting on the above, we can see that there was a dramatic shift in the understanding of karma. When it was limited to the actions— the rites—performed only by priests, the divine powers and grace that could change lives for the better were only in the hands of priests. When karma evolved to a more general notion of action and reaction, it was democratized. The power to affect the experiences of our lives and to change are now in the individual’s hands.

It is important not to reduce the law of karma to a fixed destiny. On the contrary, it is about the freedom to make decisions and to learn from the consequences of those choices. Karma is about how we learn, grow, and create our destiny ourselves.

In Jainism, karma is considered a subtle form of matter. The seeker needs to be freed from karma in order to attain liberation

vipāka = reactions; ripe, mature, effect, result, the consequence of actions in the present or former births

from vi = away + pāka, from pac = to cook, cooking

āśayair = storehouse; accumulation, receptacle, storage, or deposit of samskaras, residue, stock, balance of fruits from past actions

from a = hither, unto + śaya = lying, resting, abiding, from śī = rest, lie

aparāmṛṣṭaḥ = untouched

from a = not + mrṣ = to touch or stroke + parā = other, another, subsequent, away, off, aside

puruṣa = left untranslated; soul, spirit, human being, humankind, witness of prakriti, Seer (passive spectator of prakriti; the term most used by Patanjali), knower within, indwelling form of God, cosmic person, the pupil of the eye, the first human and source of the universe, Supreme Being, a member or representative of a race or generation, officiant, servant, an officer

possibly from pur = the body, the stronghold of spirit, or puru – a man, male, human being

viśeṣa = unique; distinct, difference between, characteristic difference, peculiar mark, special property, excellence, superiority, individuality, essential difference, individual essence, extraordinary, abundant

Ishvara is a unique Purusha. What does this mean? We are all purushas; all beings are purushas, individual sentient beings. Ishvara is also a Purusha, an individual sentient being, but unique, distinct, special, extraordinary, abundant.

There is a beautiful and important paradox here. Ishvara is divinity, but not the highest Divinity. The sutra suggests that Ishvara is a Purusha like us, yet Ishvara stands apart, is unique. In the next sutra, Patanjali will begin to describe the ways in which Ishvara is unique.

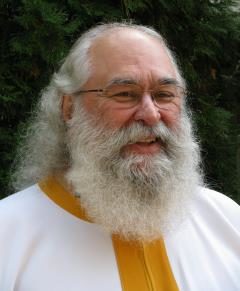

About the Author:

Reverend Jaganath Carrera is and Integral Yoga Minister and the founder/spiritual head of Yoga Life Society. He is a direct disciple of world renowned Yoga master and leader in the interfaith movement, Sri Swami Satchidananda—the founder and spiritual guide of Satchidananda Ashram–Yogaville and Integral Yoga International. Rev. Jaganath has taught at universities, prisons, Yoga centers, and interfaith programs both in the USA and abroad. He was a principal instructor of both Hatha and Raja Yoga for the Integral Yoga Teacher Training Certification Programs for over twenty years and co-wrote the training manual used for that course. He established the Integral Yoga Ministry and developed the highly regarded Integral Yoga Meditation and Raja Yoga Teacher Training Certification programs. He served for eight years as chief administrator of Satchidananda Ashram–Yogaville and founded the Integral Yoga Institute of New Brunswick, NJ. He is also a spiritual advisor and visiting lecturer on Hinduism for the One Spirit Seminary in New York City. Reverend Jaganath is the author of Inside the Yoga Sutras: A Sourcebook for the Study and Practice of Patanjali’s Yoga Sutras, published by Integral Yoga Publications. His latest book, Patanjali’s Words, is a work-in-progress.

Reverend Jaganath Carrera is and Integral Yoga Minister and the founder/spiritual head of Yoga Life Society. He is a direct disciple of world renowned Yoga master and leader in the interfaith movement, Sri Swami Satchidananda—the founder and spiritual guide of Satchidananda Ashram–Yogaville and Integral Yoga International. Rev. Jaganath has taught at universities, prisons, Yoga centers, and interfaith programs both in the USA and abroad. He was a principal instructor of both Hatha and Raja Yoga for the Integral Yoga Teacher Training Certification Programs for over twenty years and co-wrote the training manual used for that course. He established the Integral Yoga Ministry and developed the highly regarded Integral Yoga Meditation and Raja Yoga Teacher Training Certification programs. He served for eight years as chief administrator of Satchidananda Ashram–Yogaville and founded the Integral Yoga Institute of New Brunswick, NJ. He is also a spiritual advisor and visiting lecturer on Hinduism for the One Spirit Seminary in New York City. Reverend Jaganath is the author of Inside the Yoga Sutras: A Sourcebook for the Study and Practice of Patanjali’s Yoga Sutras, published by Integral Yoga Publications. His latest book, Patanjali’s Words, is a work-in-progress.