Sutra 1.23: īśvara-praṇidhānā vā

Or [samadhi is attained] by devotion with total dedication to God (Ishvara) (Swami Satchidananda translation).Or asamprajnata samadhi can be attained by wholehearted devotion and dedication to God (Ishvara) which displaces self-centered personal desires and naturally fosters contemplative absorption (Rev. Jaganath translation).

īśvara = left untranslated; master, lord, king, able to do, capable, God, supreme soul, Supreme Being, the god of love, the energies (shakti) of a goddess, a husband (See 1.23, 1.24, 2.1, 2.32, 2.45)

from iś = to rule, to own, to command, to be valid or powerful, to be master of, to reign, to behave like a master, supreme spirit + vara = valuable, eminent, choicest, suitor, lover, most excellent or eminent, better than, from vṛ = to choose

Ishvara is a term found in many sacred texts of India, including the Upanishads and the Bhagavad Gita. A good general understanding of Ishvara is that it is the reflection of the Absolute (Brahman) on the purest aspect of prakriti (sattva, that which has the nature of pure beingness), like the sun reflecting on a perfect mirror. We see the sun. We can benefit from its light and even feel some of its heat. The mirror allows us to experience several real characteristics of the sun.

In Hinduism, interpretations of what Ishvara is may differ but they share the sense of Ishvara as the cosmic governing force and intelligence of the universe, master and lord over all that is valuable. The lordship of Ishvara extends to the individual self as well as to the entirety of the universe. Any name and form of the Divine can be taken as Ishvara for the sincere devotee.

Within the hearts of all beings resides the Supreme Lord (Ishvara) and by the Lord’s power, the movements of all beings are orchestrated as if they were figurines on a carousel.

~Bhagavad Gita

Ishvara serves as a role model for seekers who strive to manifest within themselves Ishvara’s innate freedom from ignorance, obstacles, karma, and subconscious impressions.

Devotion to Ishvara harnesses the power of a loving, devoted heart to one’s spiritual quest. Devotion and dedication directed to Ishvara have the power to awaken selfless love, the perfect inner environment for attaining self-mastery and which is also a natural counterforce to all vices and limitations. Selfless love generates a force that brings the devotee to liberation. Look ahead to sutra 2.45: By wholehearted dedication to Ishvara, perfection in samadhi is attained.

It is noteworthy that Patanjali gives no physical description of Ishvara. There is no one name and form assigned to Ishvara, although many Hindu deities are called by that name. Think of Ishvara as a screen upon which any name and form of the Divine can be projected. Wherever the devotee perceives the qualities of Ishvara, that is Ishvara for her or him (see 1.24). That is why even one’s Guru can be taken as a form or expression of Ishvara.

Please note one more important aspect of Ishvara pranidhanam. Namely, Patanjali affirms the importance of not allowing the limited ego to be the beginning, middle, and end of life. We flourish and find peace and meaning in life when we have a reference point—a transcendent reality—outside of a private “I.”

In other words, Ishvara pranidhanam helps prevents us from becoming our own personal gods. Instead, Yoga (and all faith traditions) teach the value of humility, and of being able to embrace the paradox of being fully human and fully divine. If we never learn to comfortably embrace this paradox, we can never know the inner workings of harmony and peace.

praṇidhānā = devotion, dedication, displace self-centered personal desires; to hold within and in front of, profound religious meditation, vehement desire, attention paid to, laying on, fixing, applying, access, entrance, exertion, endeavor, respectful conduct, abstract contemplation of, vow

from pra = before or in front + ni = down into or within + dhā = place, put, or hold

The essence of this very important word is to put something (or someone) first, before oneself. Reading through the various definitions, you can see that the term also implies strong intent and steady focus. This resonates with Matthew 6:33: But seek first the kingdom of God and His righteousness, and all these things will be added unto you.

Pranidhana is about cultivating priorities, focus, intention, and action—all based on love and reverence. It is describing an intimate relationship with that which is transcendent and that wields the power of self-transformation. It can also be described as nurturing an intimate relationship with the Great Mystery of life itself.

Looking at the roots of pranidhana, we can see how it implies a heart-centered mindset: to place down within and before. It suggests a state of loving reverence. True love naturally promotes a selfless state of mind, a mindset where the object of love is always in the forefront of awareness. In Ishvara pranidhana, the object of love is God.

Contemplating Ishvara pranidhanam and attempting to live it in our lives, we inevitably confront a vital question, a question rooted in our need to be appreciated, acknowledged, and loved. First, let’s look at how hard we work to fulfill these needs by being good at what we do and by being a good person—both noble pursuits. We also look for signs of our worth, usually by status and possessions. In short, we feel we need to earn the right to be loved. Here’s the question: Do we look to the world or to God for love and for our worth?

Ishvara pranidhanam nudges us to look to Ishvara /God. It is here that we find that we have always been loved and that we need not do anything to earn that love. Our worthiness is innate in us. Nothing else is needed. This transformative realization is the basis of svadharma, our unique purpose for being.

Our worth—to ourselves and to others—and our discovery of our purpose for being all begins with dedication, our wish to find our ever-existing roots and connection to our True Self. Consider this quote:

The dedicated immediately enjoy an unbroken state of supreme peace.

~Bhagavad Gita 12.12

The final and sweetest fruit of dedication to Ishvara is enlightenment. We can interpret this sutra as being about surrender to God, or Source. But, for many of us, surrender implies a slavish loss of freedom. True surrender is not. It is readiness to serve combined with trust in the fact that we are loved by that Source and Essence that gave and gives us life. Even for those who are not of a devotional nature, readiness to respond to life with trust in its innate wisdom, is a vital aspect of spirituality.

To trust that we are loved unconditionally arises when our suffering has reached its limit and we have nowhere else to turn except to God or Guru or when we are the object of complete unconditional forgiveness. It is from this trust that gratitude grows, from gratitude comes faith, and from faith, a readiness to serve. This is the essence of surrender from a spiritual perspective.

In Buddhism, pranidhana is part of bhadracharya pranidhana (Vows of Good Conduct) that includes inexhaustible service to all buddhas; learning and obedience to all teachings of all buddhas; lamentation with the intention of calling forth all buddhas to descend into the world; the teaching of the dharmas (universal truths) and the paramitas (transcendental virtues) to all beings; the embracing of all universes; the bringing together of all Buddha’s lands; the achievement of Buddha’s wisdom and powers to help all beings; the unity of all bodhisattvas; and the accommodation of all sentient beings through the teaching of wisdom and Nirvana. These are bodhisattva vows, meant to express a mind directed toward enlightenment. In Mahayana Buddhism, this vow is taken by laypersons as well as monks and nuns.

va = or; either, on the one side—or on the other, either-or, to blow (as the wind), to procure or bestow anything by blowing

The word va, or, appears in this sutra for a reason. The implications suggested by this simple word casts an interesting light on the process of choice. Va is also the root of the Vayu, the Hindu god of wind. Vayu is regarded as the breath of the cosmos, as Spirit, and as the mantra, OM (see sutra 1.27 on pranava). Vayu, as cosmic wind, saturates, shatters, and cleanses. The Book of Psalms and the Koran equate winds with angels—God’s messengers. Travelers know well that it is much easier to go with the wind at their back than facing it. Just as we hope to travel with the wind at our backs, we hope to travel the spiritual path in harmony with the flow of nature (prakriti) that exists to give experiences and liberation to the individual. (see 2.18)

Could it be that “or” is only meant to simply present us with two choices to mull over, or could it be a subtle call to attempt to tune into which direction the “spiritual wind” is blowing? A clear, meditative mind can often trace the subtle movements of life that have been and are shaping us. Could or in a yogic context suggest that seekers should strive to put God’s will above self will?

In the spiritual arena, choice is not solely based on personal preference or on financial or social advantage. Choice includes assessing the impact of our options on our spiritual growth and on its impact on others and our planet.

Look at this sutra again. In the previous two sutras, Patanjali tells us that intense practice brings the realization of the goal of Yoga quickly. First, we get a picture of mastery over the mind and senses that arises through intense, sustained practice. Then we are presented with another option: We can explore devotion as a source of deep, powerful support for our practices. No emotion is stronger than loving devotion. The path of exertion of willpower and of heartpower is an example of Patanjali’s holistic approach.

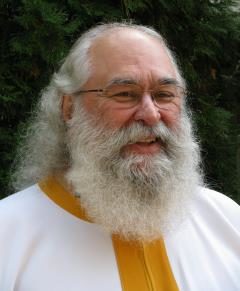

About the Author: