Rev. Jaganath, Integral Yoga Minister and Raja Yoga master teacher, has spent a lifetime delving into the deepest layers of meaning in Patanjali’s words within the Yoga Sutras. Our series continues with sutra 2.29. In several prior sutras, Patanjali explained how Self-realization, the goal of Yoga, is blocked by the kleshas. In sutra 2.29, Patanjali explains how the kleshas can be removed by following the eight-fold path of Yoga.

Rev. Jaganath, Integral Yoga Minister and Raja Yoga master teacher, has spent a lifetime delving into the deepest layers of meaning in Patanjali’s words within the Yoga Sutras. Our series continues with sutra 2.29. In several prior sutras, Patanjali explained how Self-realization, the goal of Yoga, is blocked by the kleshas. In sutra 2.29, Patanjali explains how the kleshas can be removed by following the eight-fold path of Yoga.

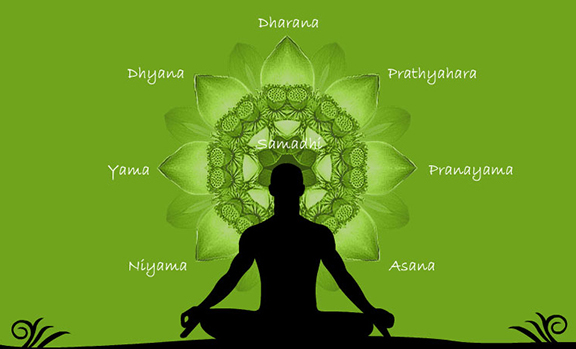

Sutra 2.29: yama-niyama-āsana-prāṇāyāma-pratyāhāra-dhāraṇā-dhyāna-samādhayo’ stāv- aṅgāni

The eight limbs of Yoga are:

- yama = universal resolves that foster harmonious relationships to self, others, and life

- niyama = additional resolves taken on by yogis to encourage spiritual growth

- asana = posture

- pranayama = regulation of breath

- pratyahara = management and withdrawal of the senses

- dharana = concentration

- dhyana = meditation

- samadhi = absorption

yama = universal governing principles; govern, self-control, holding back, moral duty, any rule, rein, curb, bridle, a driver, suppression

from yam = hold, support, reach, restrain, to establish, to be firm, not budge, to give one’s self up to, be faithful, obey, to sustain, to raise, wield (a weapon), to stretch out, expand, spread, display, govern, subdue, to offer

The yamas are classified as universal because they apply to all social divisions and categories of people and because they are to be applied regardless of the era we live in or situations we are experiencing.

However, it is important not to equate their universality as meaning that they are morals that we blindly or unthinkingly cling to. That would lead to rigidity. Instead, the yamas are more like guides that nudge us toward the awakening of our innate inner guidance system, our inner light. Through study, contemplation, practice, mindfulness, and guidance, we uncover the spirit that animates the yamas. Though we necessarily begin with the letter of the “law,” it is the spirit that we ultimately follow, how to apply these resolves faithfully and intelligently in daily life.

Using the yamas as guiding lights help us learn how to make wise decisions and take life paths that bring growth and benefit. When our inner guidance system awakens, we find that memorized morals are not needed. Our vision will naturally express virtue itself.

Wise or virtuous decisions are those that bring the highest good for the most people.

niyama = additional resolves taken by yogis; any fixed rule or law, obligation, a minor or lesser vow or observance dependent on external conditions and not as obligatory as yama, any act of voluntary penance or meritorious piety, to stop, hold back, detain, to stay, remain, to fasten, tie to, to bring near, govern, regulate

from ni = down, into + yam = restrain, reach

Although, by strict word definition, niyama is not regarded as being as obligatory as yama, for the yogi, the niyamas are regarded as being equally vital as the yamas.

Yamas represent universal moral codes of behavior. They cross over all religious, cultural, and temporal lines. The niyamas represent the ethics – morals applied to a specific group that helps guide behavior. Within the group, the ethics are regarded and treated the same as morals.

āsana = posture; position, sitting down, to be present, exist, sitting in a particular posture, a seat, couch, place, stool, abiding, dwelling, maintaining a post against an enemy

from ās = sit, be, dwell, abide, remain, continue, continue doing anything, to cease, to have an end, solemnize, celebrate, do anything without interruption, to last

Here, this word refers to the posture assumed for meditation. The fact that the definitions include to exist, abide, to be present suggests that the posture adopted by the practitioner should be comfortable enough to be maintained for prolonged periods of meditation without discomfort.

prāṇāyāma = regulation of breath; from prana, from pra = before, forward + an = breathe + yāma = restrain

pratyāhāra = management and withdrawal; retreat, holding back (especially of the senses), drawing back (troops from battle)

from prati = against, back + a = unto + hara, from hr = take, hold

Both management and withdrawal are used to indicate that pratyahara can refer to the wise use of the senses as well as the necessary withdrawal of sense input. This is a necessary stage for the practices of dharana, dhyana, and samadhi.

Since it is the initial turning of attention within, pratyahara begins, in earnest, the journey from belief to self-transformation for most seekers.

dhāraṇā = concentration; act of holding, retaining, wearing, supporting, protecting, preserving, maintaining, understanding, intellect, firmness, steadfastness, certainty, the two female breasts

from dhṛ (or dhā) = hold, maintain, to put, place, lay on or in, bestowing, have, cause, name of Brahma, the creator in Hinduism or Brahma as the Supreme Absolute Reality

If we review the different translations of dharana, we will find a correlation between the ability to hold attention, the intellect, and understanding. A focused mind can come to understand anything since it has a natural – an innate ability to probe whatever it holds its steady focus on.

A noteworthy definition is the two female breasts. Combining this with definitions such as holding and protecting, we can reframe the practice of concentration as one of nurturing rather than a forced practice that can veer into bullying the mind.

dhyāna = meditation (See 1.39, 3.2, 3.11, 3.30, 4.6)

Possible derivations:

- dhā = placing, putting, holding, possessing, having, bestowing, granting, causing, virtue, merit, wealth, property + ya = to go forward, moving or going, support, meditation, arrive at, approach, vagina, restrain, attain, to find out, behave, withdraw

- dhi = religious thought, mind, meditation, splendor, light, prayer, devotion, receptacle + ya = to go forward, moving or going, support, meditation, arrive at, approach, vagina, restrain, attain, to find out, behave, withdraw; dhi & dha are related terms. Dhi may have derived from dha, a stronger term

- dhyai = meditate, think of, contemplate

Historically, dhih, a Vedic term, precedes dhyana. In dhih, a specific deity is visualized. Often translated as thought, dhih means visionary insight, or a thought-provoking vision. These insights are said to have often inspired songs, poems, prayers, and hymns.

As with dharana, we find what seems to be an odd or out of place definition for dhyana: vagina (womb). With dharana, we found evidence of nurturance: breastfeeding. With dhyana, a deeper practice, we go deeper, to the womb, a place of perfect nurturance, the ideal environment for the beginning of life.

This reinforces the idea that meditation practice requires an inner environment of gentility, kindness, and nurturance. It also suggests that self-discipline is not just a matter of will power, but of heart power. Any practice or lifestyle change needs to be motivated and fed by love for what it is and what it will bring.

samādhi = absorption; joining or combining with, contemplation, intense concentration, unified state of awareness, bringing into harmony, joining with, attention, whole, accomplishment, conclusion, union, concentration of thoughts, profound meditation, enstasy (joy from within), super-conscious state, bringing into harmony, completion

Although samadhi without any qualifiers (such as nirvitarka, etc.) usually refers to the highest state of enlightenment, here and in other sutras, it may refer to a number of states of mental absorption. These deep meditation experiences bring profound intuitive insights into the object of contemplation, or in higher states, the meditators themselves.

Patanjali uses the term, nirbija samadhi or kaivalya to refer to the highest states. We can also add the word Yoga to this list, referring to the experience of realizing a state of unity of Seer and seen. Refer to 1.20 for more on samadhi.

aṣtau = eight

aṅgāni = limbs (See 2.28)

About the Author:

Reverend Jaganath Carrera is and Integral Yoga Minister and the founder/spiritual head of Yoga Life Society. He is a direct disciple of world renowned Yoga master and leader in the interfaith movement, Sri Swami Satchidananda—the founder and spiritual guide of Satchidananda Ashram–Yogaville and Integral Yoga International. Rev. Jaganath has taught at universities, prisons, Yoga centers, and interfaith programs both in the USA and abroad. He was a principal instructor of both Hatha and Raja Yoga for the Integral Yoga Teacher Training Certification Programs for over twenty years and co-wrote the training manual used for that course. He established the Integral Yoga Ministry and developed the highly regarded Integral Yoga Meditation and Raja Yoga Teacher Training Certification programs. He served for eight years as chief administrator of Satchidananda Ashram–Yogaville and founded the Integral Yoga Institute of New Brunswick, NJ. He is also a spiritual advisor and visiting lecturer on Hinduism for the One Spirit Seminary in New York City. Reverend Jaganath is the author of Inside the Yoga Sutras: A Sourcebook for the Study and Practice of Patanjali’s Yoga Sutras, published by Integral Yoga Publications. His latest book, Patanjali’s Words, is coming soon from Integral Yoga Publications.

Reverend Jaganath Carrera is and Integral Yoga Minister and the founder/spiritual head of Yoga Life Society. He is a direct disciple of world renowned Yoga master and leader in the interfaith movement, Sri Swami Satchidananda—the founder and spiritual guide of Satchidananda Ashram–Yogaville and Integral Yoga International. Rev. Jaganath has taught at universities, prisons, Yoga centers, and interfaith programs both in the USA and abroad. He was a principal instructor of both Hatha and Raja Yoga for the Integral Yoga Teacher Training Certification Programs for over twenty years and co-wrote the training manual used for that course. He established the Integral Yoga Ministry and developed the highly regarded Integral Yoga Meditation and Raja Yoga Teacher Training Certification programs. He served for eight years as chief administrator of Satchidananda Ashram–Yogaville and founded the Integral Yoga Institute of New Brunswick, NJ. He is also a spiritual advisor and visiting lecturer on Hinduism for the One Spirit Seminary in New York City. Reverend Jaganath is the author of Inside the Yoga Sutras: A Sourcebook for the Study and Practice of Patanjali’s Yoga Sutras, published by Integral Yoga Publications. His latest book, Patanjali’s Words, is coming soon from Integral Yoga Publications.