Rev. Jaganath, Integral Yoga Minister and Raja Yoga master teacher, has spent a lifetime delving into the deepest layers of meaning in Patanjali’s words within the Yoga Sutras. Our series moves ahead to sutra 2.35. With this sutra, Patanjali begins to map out how the precepts and practices of Raja Yoga yield profound results.

Rev. Jaganath, Integral Yoga Minister and Raja Yoga master teacher, has spent a lifetime delving into the deepest layers of meaning in Patanjali’s words within the Yoga Sutras. Our series moves ahead to sutra 2.35. With this sutra, Patanjali begins to map out how the precepts and practices of Raja Yoga yield profound results.

Sutra 2.35: ahimsā-pratiṣthāyām tat-sannidhau vaira-tyāgaḥ

In the presence of one who is firmly established in nonviolence, hostility recedes.

“This is the unusual thing about nonviolence — nobody is defeated, everybody shares in the victory.” —Martin Luther King Jr.

ahimsā = nonviolence (See 2.30)

pratiṣthāyām = established; abiding, standing firmly, steadfast, leading to, famous, center or base of anything

from prati = against, back, in opposition to, again, in return, upon, towards, in the vicinity of, near, beside, at, on, on account of + ṣthāyam, from sthā = to stand, to stand firmly, station one’s self, stand upon, to take up a position on, to stay, remain, continue in any condition or action, to remain occupied or engaged in, be intent on, make a practice of, keep on, persevere in any act, to continue to be or exist, endure, to be, exist, be present, be obtainable or at hand, to be with or at the disposal of, belong to, abide by, be near to, be on the side of, adhere or submit to, acquiesce in, serve, obey, stop, halt, wait, tarry, linger, hesitate, to behave or conduct oneself, to be directed to or fixed in, to be founded or rest or depend on, to rely on, confide in, resort to, arise from, to remain unnoticed, be left alone, to affirm, settle, determine, direct or turn towards

The word translated as firmly established, pratishthayam, is feminine in gender (as is ahimsa). In Eastern metaphysics, the feminine represents power, shakti. But shakti is power that is not limited to aggressive strength, which has its vital uses, but is one dimensional.

Aggressive strength seeks to create and then defend boundaries, to amass and hold onto power. Shakti encompasses the power to generate, innovate, and to create. In short, it is the kind of power needed to create the possibilities for poking holes in the walls that hostility creates. All this means is that our recourses for ending violence should not be limited to force, but through finding points of unity, harmony, and creative solutions to our conflicts.

tat = (refers to ahmsā); that

sannidhau = presence; nearness, proximity

from sam = with, together + ni = down, back, in, into, within + dhi, from dha = put, place

vaira = hostility; animosity, enmity, detrimental, revengeful, grudge, quarrel or feud with, a hostile host

from vīra = vehemence, hostility, animosity, enmity, passion, ardor, violence, urging, enthusiasm, strength, vigor, intensity, fully, zeal, hero, brave or eminent person, chief, son

It will be helpful to consider the meanings of hostile. Hostility is from the Latin, hostilis = stranger, enemy. Although empathy is innate in us, unfortunately, we can learn to be suspicious of people who are different from us. In more egregious cases, those outside our group are devalued, even hated.

Fear and ignorance create an isolating bubble of comfort and security within our group. We need to be mindful that there is a short road that can lead from being a loyal group member to someone who has allowed fear, stereotypes, negative opinions, and mistrust to creep into the heart. In such cases, while we can be loyal, generous, and empathetic to members of our group, we tend to create barriers (born of ignorance) between us and those we consider outsiders. This unbalanced mindset can readily bloom into harmful prejudicial, even violent behaviors directed toward those outside our group.

Minds that react to (withdraw, are suspicious of) superficialities such as skin color, political affiliations, faith traditions, sexual preferences, and nationality are vulnerable to fear-based hostility that can manifest as unfriendliness, lack of sympathy, conflict, anger, opposition, resistance, hatred, spite, antagonism, confrontational words or acts, unwarranted aggression, the intent or desire to do harm, or violence (harm to another that is planned or that arises spontaneously).

All of these attitudes and behaviors start with a mindset of intense ill will.

Let’s now look to the Sanskrit to complete this analysis: One definition of the root, vira, is especially interesting in the context of this sutra: vehemence, a display of strong feelings, to urge, to be enthusiastic. This suggests that the hostile person’s or persons’ anger gives rise to feelings of greater strength (most often we overestimate our anger-enhanced strength) and righteous anger (refer to vira’s definitions of hero, brave, eminent).

The combination of self-perceived greater strength and righteous anger (against others perceived as threats) give license to do violence that the individual or individuals misperceive as altruistic acts. A prime example are terrorists who sanction acts of violence against innocents as holy or virtuous.

It is noteworthy that those who engage in hostile acts often do not arrive at that state through clear, objective, reason, but by strong feelings often manipulated by those with authority, or through propaganda, or other influences. This being so, reasoning is often not a viable counterforce to inflamed hostility. In fact, reason can lead such people to cling to their misperceptions and hostilities more strongly. Such individuals actively seek arguments that support their views, a mindset known as confirmation bias. Especially in such cases, people resist abandoning a false belief unless they have a compelling alternative.

Yoga offers such an alternative: one firmly established in harmlessness, an understanding of humanity’s common struggles and pain, the power, peace and joy of faith, and the freedom of knowing that we are all one in Spirit.

Understanding this sutra as if it were describing a miracle – someone established in ahimsa walking into the middle of a violent confrontation and causing everyone to spontaneously drop their weapons – is tempting, and based on deep wishes for peace and harmony. History clearly tells a different story. Great sages and saints have not always been able to quell violence or hatred. Some have been murdered or executed. So, what is this sutra really saying?

The practical and very real and powerful message of this sutra is that the mere presence – demeanor, words, and actions – of one firmly established in ahimsa generates a space, even if a small one, for entrenched feelings and misperceptions to recede. This is no small feat.

Keep in mind that nearly 95 percent of communication is nonverbal. The masters of harmlessness radiate compassion, harmony, and hope in countless subtle and powerful ways. Yet, the minds of those in their presence need to be open – at least a little – to receive that vibration in order to abandon, change, or modify strongly held beliefs. But given even a tiny opening, the presence of the enlightened peacemakers can work wonders.

Blessed are the peacemakers for they shall be called children of God. —Matthew 5:9

The above quote indicates that peace is the master plan of the universe, even though so often it does not seem to be so. Those who seek peace within and without, who become radiators of peace are aligning themselves with the deepest, subtlest forces of the universe.

tyāgaḥ = recedes; withdraw, abandonment, leaving behind, giving up, resigning, to offer, sacrificing one’s life

from tyaj = renounce, to leave, abandon, quit, go away, to let go, dismiss, discharge, to give up, surrender, resign, part from, get rid of, to free oneself from (any passion), to give away, distribute, offer, to set aside, to leave unnoticed, disregard, to cause anyone to quit

While, in the Sanskrit, tyaga is not presented as an action (it’s in the nominative case), we can still benefit from considering the breadth of meanings of the roots of this word. We can visualize hostility moving away, being transcended, or being distributed – scattered – implying that the factors that formed the foundation of the hostility have begun to unravel.

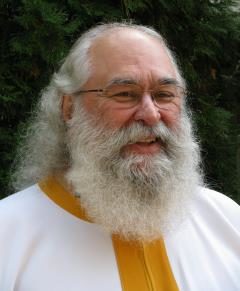

About the Author:

Reverend Jaganath Carrera is and Integral Yoga Minister and the founder/spiritual head of Yoga Life Society. He is a direct disciple of world renowned Yoga master and leader in the interfaith movement, Sri Swami Satchidananda—the founder and spiritual guide of Satchidananda Ashram–Yogaville and Integral Yoga International. Rev. Jaganath has taught at universities, prisons, Yoga centers, and interfaith programs both in the USA and abroad. He was a principal instructor of both Hatha and Raja Yoga for the Integral Yoga Teacher Training Certification Programs for over twenty years and co-wrote the training manual used for that course. He established the Integral Yoga Ministry and developed the highly regarded Integral Yoga Meditation and Raja Yoga Teacher Training Certification programs. He served for eight years as chief administrator of Satchidananda Ashram–Yogaville and founded the Integral Yoga Institute of New Brunswick, NJ. He is also a spiritual advisor and visiting lecturer on Hinduism for the One Spirit Seminary in New York City. Reverend Jaganath is the author of Inside the Yoga Sutras: A Sourcebook for the Study and Practice of Patanjali’s Yoga Sutras, published by Integral Yoga Publications. His latest book, Inside Patanjali’s Words, is widely available.

Reverend Jaganath Carrera is and Integral Yoga Minister and the founder/spiritual head of Yoga Life Society. He is a direct disciple of world renowned Yoga master and leader in the interfaith movement, Sri Swami Satchidananda—the founder and spiritual guide of Satchidananda Ashram–Yogaville and Integral Yoga International. Rev. Jaganath has taught at universities, prisons, Yoga centers, and interfaith programs both in the USA and abroad. He was a principal instructor of both Hatha and Raja Yoga for the Integral Yoga Teacher Training Certification Programs for over twenty years and co-wrote the training manual used for that course. He established the Integral Yoga Ministry and developed the highly regarded Integral Yoga Meditation and Raja Yoga Teacher Training Certification programs. He served for eight years as chief administrator of Satchidananda Ashram–Yogaville and founded the Integral Yoga Institute of New Brunswick, NJ. He is also a spiritual advisor and visiting lecturer on Hinduism for the One Spirit Seminary in New York City. Reverend Jaganath is the author of Inside the Yoga Sutras: A Sourcebook for the Study and Practice of Patanjali’s Yoga Sutras, published by Integral Yoga Publications. His latest book, Inside Patanjali’s Words, is widely available.