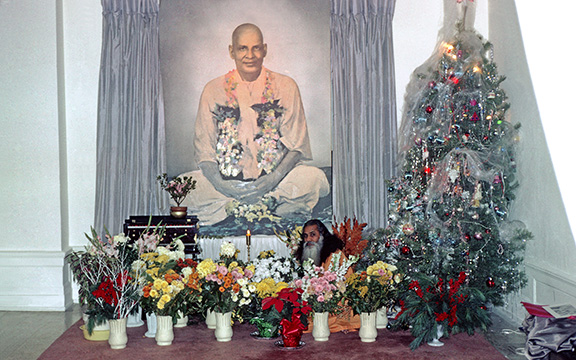

Swami Satchidananda seated in front of portrait of his Guru, Sri Swami Sivananda, during holiday celebrations, 1969.

Although it is well-suited to the present era, Integral Yoga®, as taught by Swami Satchidananda, is part of a lineage with a long history. This lineage contributes to the beauty of the Integral Yoga tradition, in that it is part of a tradition. Today, with the popularity of Yoga and its many different adaptations in the West, there has been a movement to erase and downplay its historical roots. And, in response, there has been sharp criticism, mainly by Hindus, about the movement’s expropriation of the term, “Yoga.” So, what does it mean to be part of a lineage and what value does this hold for the tradition and for students who follow it?

The first mention of Yoga appears in the Rig Veda, a sacred Indian text that is believed to have been composed around 1500 BCE, but it has been speculated that Yoga may even pre-date the Vedic texts by thousands of years. Despite its ancient origins, Yoga has been passed on from generation to generation, surviving the test of time. Lineage has played an integral role in the dissemination of Yoga wisdom throughout the ages. In Eastern traditions, lineage refers to the descent of spiritual teachings from Guru (teacher) to student over time.

“When you study Hindu scriptures, it’s difficult to avoid the topic of lineage,” says Integral Yoga teacher Satyam Penn, a professor at the University of Toronto, a passionate student of Sanskrit, and a yogi for more than 30 years. “If you look at a book like Patanjali’s Yoga Sutras, back then people wouldn’t have just dived into the original text and thought about what Patanjali must have meant. They would have the Yoga Sutras, a commentary on the Yoga Sutras, commentaries on the commentaries of the Yoga Sutras, and so forth. There would have been an entire lineage of documents attached to that original scripture, all of which served the purpose of further elucidating or elaborating on that basic message. So anyone in pre-colonial India would have had to approach this topic from the standpoint of associating themselves with a lineage, often through their families or their teachers. They would become immersed in that tradition. It was a tradition they inherited and a tradition they would then serve to pass on to other people.”

The value of lineage could be easily lost on contemporary yogis practicing in the West, where various styles of Hatha Yoga proliferate and very few inherit Yoga traditions from their families. “Now, of course, things are a little bit different,” Satyam agrees. “People kind of shop around for paths.” That begs the question: Is lineage meaningful or even relevant in the modern era?

“It definitely changes things up to be part of a lineage,” Satyam says. Not only do you have access to great spiritual wealth and wisdom through lineage, but he suggests that, as with any spiritual discipline, you become part of something much greater than yourself. “What you’re being given is an opportunity really, a privilege, to transmit that tradition to future generations.” Once you realize how you have benefited from your path, Satyam says, “think about how many people so many years from now will benefit as well. It’s up to us to pass that on. That happens not through a text alone. There’s a kind of spark that’s transmitted through lineage. When a Guru gives mantra initiation, that spark is passed on. ‘It’s like a seed,’ Sri Swami Satchidananda said.”

Sri Swami Satchidananda, lovingly called Sri Gurudev by his students, was responsible for the transmission of the “spark” that is the lineage of the Integral Yoga tradition. Integral Yoga swamis (monks) and ministers can trace their lineage from Sri Swami Satchidananda to his Guru, Swami Sivananda, whose Guru was Swami Vishwananda. Adi Shankaracharya is the founder of this and several other monastic lineages in Hinduism.

When we consider the history of Yoga and the importance of lineage in the transmission of the practices, the significance of the Guru-disciple relationship in Eastern traditions also comes to light. Gurus play an essential role in sharing the teachings. Gurus are not desirous of fame or other benefits from teaching, but do so selflessly, Satyam says, “motivated by the value that they know the teachings have and their compassion for others.”

Modern yogis may choose to follow their own paths, unassociated with any particular lineage or Guru. And yet, all practitioners have lineage to thank for the existence of Yoga in the current world.

About the Author:

Alex Anandi Williams is a former teacher who currently lives with her husband, Parker Narada Williams, in the Satchidananda Ashram–Yogaville community. Up until the recent birth of her daughter, Veena, she was the editor of the Yogaville.org blog.

Alex Anandi Williams is a former teacher who currently lives with her husband, Parker Narada Williams, in the Satchidananda Ashram–Yogaville community. Up until the recent birth of her daughter, Veena, she was the editor of the Yogaville.org blog.