When I first studied Raja Yoga, or Patanjali’s Yoga Sutras, in my Yoga Teacher Training Class of 2001 at the Integral Yoga Institute, New York City, I clearly remember Swami Ramananda saying something like, “First your mind talked you into eating the ice cream, then it started saying you shouldn’t have eaten the ice cream (dramatic pause)—how can you trust your mind?” I have been asking myself that question ever since.

When I first studied Raja Yoga, or Patanjali’s Yoga Sutras, in my Yoga Teacher Training Class of 2001 at the Integral Yoga Institute, New York City, I clearly remember Swami Ramananda saying something like, “First your mind talked you into eating the ice cream, then it started saying you shouldn’t have eaten the ice cream (dramatic pause)—how can you trust your mind?” I have been asking myself that question ever since.

Lucky for me, the Yoga Sutras give clear instructions on bypassing the mind, not getting caught up in its whirlwinds of “do it; no, don’t do it; do it; ah, you shouldn’t have done that.” The Sutras’ aim is to help calm those whirlwinds, slow them way down so I can see, hear between the gaps for other options of action, options I like to think come from life, Divine Consciousness, True Self. I became so enamored with the Sutras that I received Teacher Training for them and taught several Raja Yoga classes to new Yoga Teacher Trainers in New York. Each time, I was amazed at the wisdom, the simplicity, the practicality, of the Sutras.

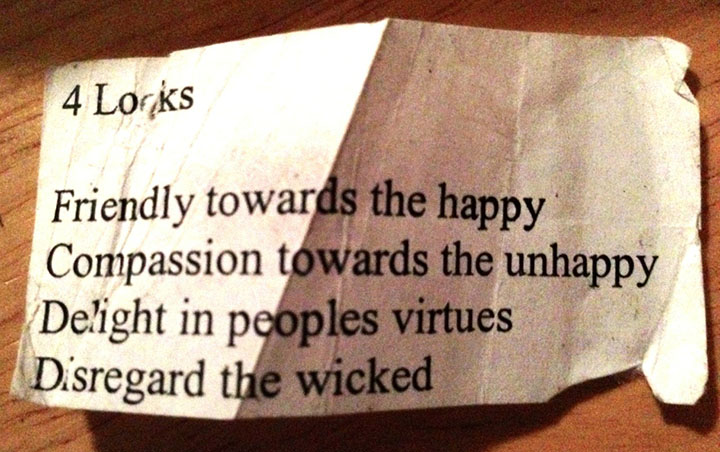

Of course, the most well known Sutra is the second one, Yogas Chitta Vritti Nirodah, the restraint of the modifications of the mind-stuff is Yoga. To me, this is the lynchpin around which all other sutras revolve. No matter what sutra we look at, it comes back to this truth. We experience union, or Yoga, when the mind’s whirlwinds calm down. However, as Patanjali proceeds through the first pada, or section of the Sutras, “On Contemplation,” there arises what Swami Satchidananda called the “Four Locks, Four Keys” sutra. Amidst the encouragement to practice devotion to God (Ishvara Pranidhana) followed by other devotional and contemplative practices, we find the Four Locks, Four Keys, a practical-as-can-be sutra that gives responses to four major types of behavior people exhibit. The lock is a human behavior that can trigger whirlwinds; the key is what keeps the mind unlocked from the whirlwinds to experience Yoga. In this sutra, Patanjali isn’t talking about practicing contemplation, he’s offering a quick fix, an immediate response to everyday situations, a simple approach to relationships. To keep our mind calm, we need only practice the key that fits the lock.

The sutra (as translated by Reverend Jaganath Carrera) reads, “By cultivating attitudes of friendliness toward the happy, compassion for the unhappy, delight in the virtuous, and equanimity toward the non-virtuous, the mind-stuff retains its undisturbed calmness.” Here, Patanjali is giving us attitudes to cultivate, not actions to take. We focus on how our heart approaches a situation, not on what our mind says we should do.

THE FIRST LOCK & KEY

Let’s look at cultivating friendliness toward the happy. This one seems like a no-brainer.

I am walking down the street and a fellow whistling and smiling comes toward me. If I were in an undisturbed calmness of mind, I could keep that state, according to the sutra, by responding to such behavior with friendliness, which might be a smile, nod, or even a hello. That seems simple enough. However, what if the fellow’s happiness triggers a sense of comparison in me, that I am not that happy, only calm. I can just hear the vrittis now, “What’s he so happy about? Did he win some money? Get a big promotion? What’s wrong with me?” It is easy to see how quickly the vrittis can spin a calm mind into a whirlwind of stories! And imagine if I meet this fellow and I don’t have a calm mind.

Instead, I’m thinking about a million things, including how to get a very important report out by the end of the day. I’m worried and unhappy, invisible vrittis encircling me much like Pigpen’s dirt cloud in the Peanuts comic strip, saying, “you are a failure, you won’t get the project done, everything is going to blow up! And why is that person so happy?” My mind could become even more agitated seeing a happy person. However, if I heeded Patanjali’s words, trusted them and responded without thought, and felt friendly toward this fellow, what might happen? A smile might break my agitated thought pattern, my body reading a signal of happiness, and suddenly, my mind might calm (or at least there would be a break in the vrittis) and I am in a position to experience Yoga, or union, joining a fellow human in a happy feeling.

Two exciting things come from the example above. First, this sutra can work both ways. We can keep a calm mind showing friendliness toward the happy, and, we can calm a whirlwind mind by doing the same thing! Second, when we use it to calm our minds, it can happen instantly. It only takes a moment to drop the vrittis and experience Yoga. Amid all the concentration guidance in the first pada of the Sutras, which can sometimes sound challenging, Patanjali gives us this chance to experience instant Yoga (or not fall out of it) simply by responding with a particular attitude to a particular behavior.

THE SECOND LOCK & KEY

The second lock and key is cultivating compassion toward the sad. Again, this seems so straight forward. Yet, many of us have different definitions of compassion. To some it means to be “nice,” to others it might mean “tough love.” Again, Patanjali doesn’t give us any guidance on action, only on attitude so it would be helpful here to explore what compassion means. According to Merriam-Webster, compassion is “a feeling of deep sympathy and sorrow for another who is stricken by misfortune, accompanied by a strong desire to alleviate the suffering.” Pema Chodron has been know to define compassion as “an armless mother watching her child fall into a raging river.” Brene Brown suggests compassion is “allowing another to be vulnerable, exposed, loved, and accepted all at the same time;” and also that, “compassion is a relationship between equals. Only when we know our own darkness well can we be present with the darkness of others.”

For me, compassion has a sense of suffering alongside, without having to do anything to fix the other person. And while this may sound contrary to the dictionary definition, I don’t believe it is. I believe that suffering alongside and allowing someone to have the very human experiences of sadness, grief, trauma, and not push those emotions aside to feel better or get over them, can be the most healing, transformative, helpful action (or perhaps, non-action) we can share. However, I project that in our Western society, this may be one of the most challenging behaviors to exhibit, as being sad seems to indicated being a loser. Typical vrittis might sound like, “Get over it! Ugh, how miserable this person is. Why do I have to hear this?” Hardly anyone wants to recall their own sad times to feel compassion for someone else going through it. Mostly we want to drag that person out of sadness so we don’t have to acknowledge our own grief.

However, I have found being alongside someone who is sad, knowing I don’t have to change them, the situation, or fix anything allows me to experience compassion—I can relax and allow, let the person be vulnerable and exposed while still loving and accepting them. We are equals, and it feels natural, even easy, and from that, my mind clears and calms. I don’t have to do anything except be there, be compassion. And, as we saw before, it can work the other way. Say I have been practicing the contemplations Patanjali offered in the first pada; devotion to God, mantra repetition, pranayama, and meditation, and from those I have a calm mind. Now I can be alongside another person who feels depressed, anxious, lost, or hopeless without my mind racing with vrittis, and I can hold space for that person to experience very real, deep and human emotions without being judged. And with that calm mind, in the absence of vrittis, life or Divine

Consciousness can drop in (like an insight or an intuition) an action that might be helpful; holding the person’s hand, praying, singing and dancing, listening, sitting in silence, asking how to help. Compassion can be expressed in unlimited ways.

THE THIRD LOCK & KEY

The third lock/key is delight toward the virtuous. Again, this seems simple, especially when it comes to heroes like Mother Teresa, the Dalai Lama, and Sri Swami Satchidananda. It becomes much more challenging when it hits closer to home. If my friend and I decide to eat healthier, and my friend sticks to the commitment and I don’t, can I show delight toward my friend? Typical vrittis would most likely attack me and my friend! “She’s a show-off, a goody-two-shoes. I’m lame, a loser, and fat.” Again, I turn to Merriam-Webster for a definition of the attitude of delight: “recognition with joy; after (de-) light.” Light shines and we de-light! Patanjali is offering that by dropping the vrittis in each of these locks and keys we can resonate with, experience, be, True Nature. I imagine life, Divine Consciousness delighting when my friend sticks to her commitment to eat healthy. And I can choose to experience the same. And it all can happen in an instant!

The more we explore this, the more it appears that the Four Keys: friendliness, compassion, delight, and equanimity (which we are getting to) could all be included in the definition of True Nature. It could be that Patanjali’s attitudes are simply discreet aspects of experiencing Yoga. In this instance then, delighting in my friend’s success could calm the vrittis and give me the energy to recommit! In some ways, I see the keys continually unlocking the mind (or keeping it unlocked), so that the mind gets out of the way for the next key to work in a new situation!

THE FOURTH LOCK & KEY

The last lock/key is equanimity toward the non-virtuous. In all my years of teaching, this one seems to cause the most head shakes and grumblings. “When someone cuts me off in traffic (or on the way to the subway), I’m supposed to smile and be nice?” In a word, yes. Because Patanjali’s whole point of the Sutras is for you to experience Yoga, union. It doesn’t comment on what other people are supposed to experience, be or do. For me in particular, with respect to this part of the sutra, it doesn’t matter what someone else’s behavior is, I can always maintain a calm, peaceful mind. It is important what I do, not what anyone else does. My well-being is not at the mercy of someone else; it is all up to me.

And yet, when I look at Merriam-Webster’s definition of equanimity: “awareness of mind; right disposition, even mind,” smiling and being nice, actions, are not part of it. Again, Patanjali wants us to cultivate a heartfelt attitude. Perhaps what strikes me most about this lock and key is to not make things worse, to not spiral down. Mostly I want to maintain a calm mind in this situation, because out of all the “lock behaviors,” this one has the highest likelihood of turning harmful. And what I’ve discovered when I can keep a calm mind is that no matter what the behavior is, happy, sad, virtuous, non-virtuous, that behavior becomes information, not a judgment or a statement on who we are as humans. It’s only the vrittis that want to come up with a story, judgment or critique about what happened.

For instance, if I say something to my spouse who instantly gives me a look that I have always interpreted as severe disapproval, rather than going to a knee-jerk reaction of anger I can choose to interpret that look as information. Something caused my spouse to have that expression. Was it really what I said? By practicing equanimity, I can calmly ask about the “look” and it could easily be that while I was talking, my spouse had a moment of extreme pain from an old knee injury that caused the expression! Which leads to another beautiful part of this sutra; I don’t have to figure anything out. I need only respond how Patanjali suggests, show equanimity, even mind, toward the “look” and keep my calmness at which point, I can ask for clarification. And if it is disapproval, that equanimity can allow for endless response options that don’t include anger and may even lead to an openhearted discussion that could benefit the relationship.

In the end, Patanjali’s Yoga Sutras are aimed at encouraging me, and all spiritual students, to experience Yoga, Divine Consciousness, a calm mind. There is no quicker way for me to do that than to practice this sutra and above all, to practice it toward myself. For what more important relationship is there in my life, than the one I have with myself? When I’m happy, I shall treat myself with friendliness and not let vrittis try to shame me out of feeling happy—same with sadness, virtuous, and non-virtuous behaviors. Whatever I practice with others, I practice with myself, for I am as deserving as any other human being to be approached with friendliness, compassion, delight, and equanimity.

About the Author:

Beth Hinnen began her Yoga teaching path with the Integral Yoga Teacher Training Program in 2001. Afterward, she took the Intermediate, Advanced, Raja, and Prenatal trainings. With over 1,000 hours in Yoga certifications (including Structural Yoga Therapy), Beth taught in the New York City area for over 10 years, both privately and in classes. In 2013 she moved back to her native state, Colorado, to open a common-denominational spiritual center named Samaya (“right timing” in Sanskrit) following Sri Swami Satchidananda’s teaching, “Truth is one, paths are many.” She currently also studies Buddhism.

Beth Hinnen began her Yoga teaching path with the Integral Yoga Teacher Training Program in 2001. Afterward, she took the Intermediate, Advanced, Raja, and Prenatal trainings. With over 1,000 hours in Yoga certifications (including Structural Yoga Therapy), Beth taught in the New York City area for over 10 years, both privately and in classes. In 2013 she moved back to her native state, Colorado, to open a common-denominational spiritual center named Samaya (“right timing” in Sanskrit) following Sri Swami Satchidananda’s teaching, “Truth is one, paths are many.” She currently also studies Buddhism.