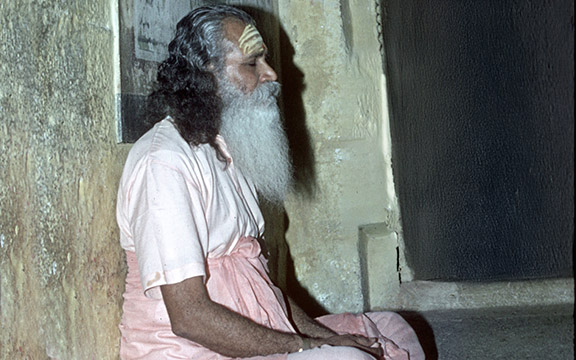

Swami Satchidananda, with sandalwood paste on forehead, meditating in Palani, 1970s.

In our last installment, Ramaswamy (Swami Satchidananda’s birth name) realized that the next step in deepening his spiritual practices would be to travel sixty miles from his birthplace of Chettipalayam to the ashram of the family Guru, Sri Sadhu Swamigal, in Palani. Upon his arrival, Ramaswamy was warmly welcomed by Sri Sadhu Swamigal.

He would spend the next two years at this ashram, and for years afterward, he spoke about the profound experiences he had there and at the Palani temple. Life at the ashram was simple but deeply transformative. He described daily life in vivid detail, offering a glimpse into the intensity and dedication required:

“Morning, early morning, we get up, meditate, or walk four miles to the river to take a bath before the sun rises. You have to even go and search for the water because you won’t see it; it’s pitch dark when you go in the morning. We would walk that far in the dark, without any flashlight or anything to light the way. It was only by touching the water that would we know we had reached the river. The river also will be more or less sleeping at that time. Gently, without disturbing the water, we would bathe and then walk back four miles.”

This early routine was not merely a test of physical endurance but a way to immerse oneself in the natural rhythm of life, in harmony with the elements. The darkness of the pre-dawn hours served as a metaphor for the seeker’s journey: navigating the unknown with faith, guided only by intuition and touch. The river, described as “sleeping,” symbolized the quiet yet dynamic presence of the Divine, awaiting gentle engagement. The act of bathing, performed with reverence and stillness, reflected a deeper spiritual cleansing.

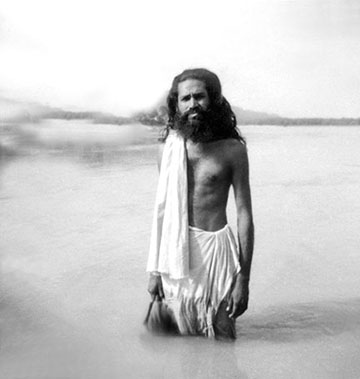

Purification in the river.

The holy area surrounding the Palani temple was the perfect place for purification, both physical and spiritual. Ramaswamy’s body naturally responded to this sacred place. He underwent a period of intense purification, during which he experienced a burning sensation throughout his body, as if it were on fire. This sensation, seemingly unprovoked, led him to spend hours in the river, seeking relief. Yet even the cooling waters could not alleviate the heat entirely.

He tried applying sandalwood paste, a natural coolant and purifier, to his body. However, this internal heat was so intense that the paste dried almost instantly. This purification process continued for several days, creating a sense of surrender and acceptance within Ramaswamy. When the burning sensation finally subsided, he emerged feeling lighter, more vibrant, and profoundly transformed.

Far from leaving him fatigued, this purification invigorated him. He described feeling as though he could fly, bounding up the nearly 1,000 steps of Palani Hill with ease. This newfound lightness extended to his mind as well, freeing him from any sense of lethargy or heaviness. It was as though his physical body had aligned with the higher vibrations of his spiritual aspirations. This period of transformation underscored the importance of cleansing not only the body but also the mind, allowing one to rise above the burdens of tamas, or inertia, and embrace sattva, the quality of lightness and harmony.

He detailed more about life in Palani, highlighting the disciplined structure of the day:

“Sometimes, if we finish the river bath and come early, we might even go around the hill, which is about three miles, and then go up. Then, we would be ready for the first service, the pre-dawn service. Only at that service will the sun begin to rise. So just imagine—count backward to see what time we had to wake up. After attending three temple worship services, we would sit somewhere quietly and meditate between the services. Then, we’d return to the ashram.”

The routine was unrelenting, yet it fostered a profound sense of discipline and devotion. The absence of creature comforts, such as breakfast, underscored the simplicity of ashram life.

“There’s no breakfast or anything served at the ashram. Sometimes the devotees, if they recognize you or feel comfortable, they may offer, ‘Swami, would you like to have a little breakfast with me?’ They will call you and you go with them and have an idli (steamed lentil and rice cake) or a little coffee, something. Otherwise, the ashram doesn’t give breakfast. Water is the breakfast.”

Such austerity sharpened the focus on spiritual practice, stripping away distractions and emphasizing humility.

“Then we would come back to the ashram and it’ll be almost 8:30 or 9 in the morning. Then we begin ashram chores. During the noon, we would meditate at the ashram in our rooms—if you have a room. If not, nap on the verandah or sleep or in the dining hall. That’s also what I would do because we don’t have any suitcases and this and that. We just have a gunny bag for our ‘queen’s mattress’ and a block of wood or a piece of brick as the pillow.”

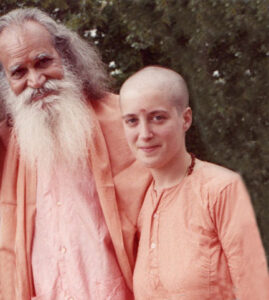

A view of Sri Sadhu Swamigal’s ashram, Palani.

Ashrams of that era typically had very basic accommodations, often without proper beds or mattresses. Visitors were expected to adapt to the simple lifestyle of the ashram, which included sleeping on the floor or on basic mats.

The term “queen’s mattress” was, no doubt, used humorously, suggesting a contrast between the luxurious connotations of a queen’s bed and the actual simple mat or bedroll Ramaswamy used in the ashram setting. This personal bedding would have been lightweight and easy to transport, allowing spiritual seekers to move between different ashrams or accommodations.

The teachings of Sri Sadhu Swamigal were imparted not through formal classes or texts but through the Guru’s presence and daily interactions. Swami Satchidananda contrasted this with his own ashram he established in America later:

“Sadhu Swamigal never gave me the Patanjali Yoga Sutras or the Bhagavad Gita to study. He simply sat with his devotees and talked. There were no formal classes. If there was any instruction, it might be something as simple as, ‘Here, take this cloth, wash it, and bring it back.’ We learned to serve with humility.”

This mode of teaching emphasized the importance of direct experience and service over intellectual study. Swami Satchidananda would later explain this dynamic to his own devotees:

“When we were with Sadhu Swamigal, we would just stand there, not knowing what would come or when. But the teachings would emerge when we were in a receptive mood. Real initiation, real teaching, doesn’t come from formal classes, reading books, or even satsangs. These are just shows. Real spiritual instruction comes through humility, dedication, and faith. It’s about how you approach your tasks and the attitude you carry.

“Today, there’s formal satsang. I sit on a big chair in front of a microphone and answer your questions; we have classes. These thing are all more intellectual. It’s all right. Modernization. But, real spiritual vibrations don’t get imparted this way. That occurs when you have the proper attitude and simply put yourself in that receptive position and you just receive it.

“There is a story of a boy who used to do the laundry of the Guru. That boy could answer every tough spiritual question while the people who took all the lessons about the Bhagavad Gita, Upanishads couldn’t answer. ‘Na karmaṇā na prajayā dhanena,’ the scriptures positively say: ‘Not by work, not by progeny, not by wealth does one attain the immortal state—liberation—but by total faith, dedication, and humility.”

Swami Satchidananda continued describing his daily routine in Palani

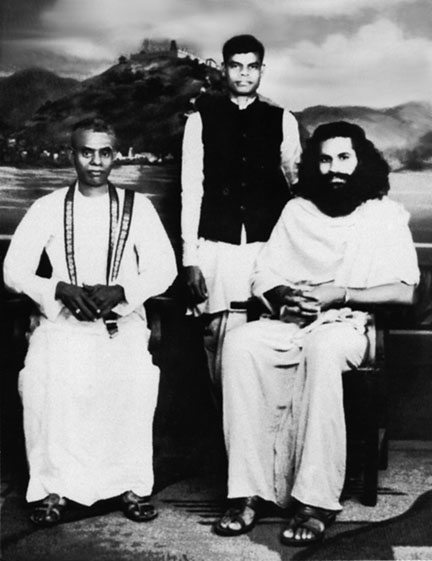

Ramaswamy with Sri Sadaiappa Chettiar and his younger brother Sri Kalidas (standing) at Palani.

“In the evening, again we would go up to the hill temple, stay until almost 9 or 9:30, the last service. Then we’d come down. When I arrive at the Ashram, two bananas and a half a cup of milk will be ready for me, placed there by a wonderful devotee who literally took care of me. His name was Kalidas and he was the Palani Adivarnam [foothills of Palani] Postmaster. When I arrive back from the temple, he will be sitting there, keeping ready the hot milk and two bananas. I’ll eat that.”

These experiences further cultivated a deep sense of gratitude for whatever was offered, however small. This gratitude became a central aspect of his practice, enabling Ramaswamy to find joy in the simplest gestures of kindness.

“Then where to go and find some place to sleep? If somebody has taken the place already that I had been using, I would find another place to sleep. That was the routine. At least in Rishikesh, you are given a little indoor sleeping because of the climate. Sometimes a room, sometimes under the staircase because there’s a little space to go down and sleep underneath. That was my room for a long time. And every time you are sent out somewhere by the time you come back, somebody else will be in that room, so you have to find another room. There’s no permanent room there.”

The nights were often punctuated by mystical occurrences. Along with another disciple, Ramaswamy would prepare Sri Sadhu Swamigal’s bed and set up the mosquito net. Sometimes, while meditating nearby, they heard the Guru conversing. When asked, Sri Swamigal would dismiss their inquiries with a firm, “Keep quiet. You don’t need to spy on me.” Later, they learned that the Guru often spoke with Lord Muruga and the Goddess, further deepening their experience of the ashram’s mystical vibrations. Each day at the ashram strengthened his resolve, purified his being, and deepened the divine connection Ramaswamy continued to experience on his spiritual journey. The time spent in Palani set an even stronger foundation for the profound wisdom and teachings he would later share with the world.

In the next installment, we will delve further into his transformative experiences at the Palani temple itself, where even greater revelations awaited.

About the Author:

Swami Premananda, Ph.D. is a senior disciple of Sri Gurudev Swami Satchidananda and served as his personal and traveling assistant for 24 years. Her interest in the study of the spiritual roots of the Integral Yoga tradition and lineage was inspired over many years of traveling with Sri Gurudev to the various sacred sites throughout India that are a part of this tradition. She also undertook a 2-year immersion into the nondual Saiva Yoga Siddhar tradition that is at the heart of Sri Gurudev’s spiritual roots. She further studied the history, sacred texts, and teachings of Tamil Saivism including the Siddhars, bhakti poet saints, as well as the spiritual luminaries who lived in the 19th – 20th centuries and who inspired Sri Gurudev, such as Sri Ramana Maharshi, Swami Ramdas, and Swami Vivekananda. She serves as editor of Integral Yoga Magazine, Integral Yoga Publications; senior archivist for Integral Yoga Archives; and director of the Office of Sri Gurudev and His Legacy.

Swami Premananda, Ph.D. is a senior disciple of Sri Gurudev Swami Satchidananda and served as his personal and traveling assistant for 24 years. Her interest in the study of the spiritual roots of the Integral Yoga tradition and lineage was inspired over many years of traveling with Sri Gurudev to the various sacred sites throughout India that are a part of this tradition. She also undertook a 2-year immersion into the nondual Saiva Yoga Siddhar tradition that is at the heart of Sri Gurudev’s spiritual roots. She further studied the history, sacred texts, and teachings of Tamil Saivism including the Siddhars, bhakti poet saints, as well as the spiritual luminaries who lived in the 19th – 20th centuries and who inspired Sri Gurudev, such as Sri Ramana Maharshi, Swami Ramdas, and Swami Vivekananda. She serves as editor of Integral Yoga Magazine, Integral Yoga Publications; senior archivist for Integral Yoga Archives; and director of the Office of Sri Gurudev and His Legacy.