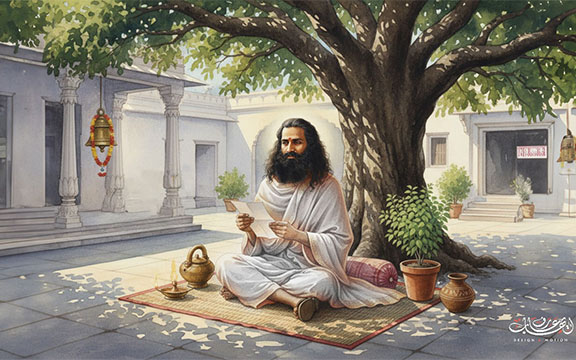

(Illustration of Ramaswamy, Avinashi Temple by Ehab Ishwara Aref.)

In the great spiritual biographies of India, there are periods that seem, on the surface, uneventful—stretches of wandering, waiting, or uncertainty. Yet these are often the hidden chapters in which the deepest transformation takes place.

For Ramaswamy, the young seeker who would one day be known to the world as Swami Satchidananda, the years 1946 through 1947 were such a period: a time in South India marked by surrender, simplicity, and the quiet imprint of great souls whose influence would echo through his later teachings.

These were the years in which the seeds of a world-embracing Yoga were planted—long before the word “Integral Yoga” became associated with his name, long before he stepped onto American soil, long before anyone could imagine the global movement that would spring from his life.

A Reluctant Role in Avinashi

Ramaswamy spent a short time in the town of Avinashi in Tamil Nadu. The spiritual head of an ashram there had recently passed away. Because several devotees knew Ramaswamy and his family, they proposed that he step into the vacant role. His reputation as a sincere seeker, devoted to meditation and an inner-turned life, made him a natural candidate in their eyes.

But his inner aspiration at this stage of life was very clear: to live simply, meditate deeply, and remain as inward as possible. He did not desire position or public responsibility; he wanted silence, not administration; solitude, not ceremony. He refused the trustees’ offer initially. Only after persistent appeals from the community did he agree, but on one non-negotiable condition: he would not be drawn into the daily affairs or management of the ashram.

It did not take long—only nineteen days—for that condition to be overrun by the practical demands of the institution. Seeing that the trustees could not honor the arrangement and sensing the danger of being pulled into day-to-day temple management when his soul longed for inner contemplation and worship, he quietly resigned and left Avinashi.

Leaving Avinashi marked a turning point, opening a period of wandering, sadhana, and quiet testing that shaped the next several years of his spiritual life. The way he stepped away from a role that did not support his inner growth also foreshadowed how he would later lead a large spiritual organization in America: always placing the spiritual evolution of an individual above the needs or advantages of the organization.

The Two Vows: Surrender as a Way of Life

Ramaswamy now resolved to surrender his life completely to God. He took two vows that would define the next year of his mendicant life:

- He would never keep money.

- He would never ask anyone for anything—not even for food.

These vows were not undertaken for drama or ascetic display. They were born of a simple conviction: “If there is a God, let me live in God’s hands. If I ask for nothing, whatever comes is God’s will; whatever doesn’t come is also God’s will.”

For the first three days he had nothing to eat. He slept on park benches, roadside embankments, or temple porticos. He bathed in temple ponds. He would not stand in the food line after morning worship; if he ate at all, it was only because a priest or devotee spontaneously approached him. On the third day, a man who noticed his frail appearance asked, “Have you eaten? You look hungry.” Only when someone offered food unasked would he accept.

This rhythm soon stabilized: he walked wherever his feet led him; he slept wherever he grew tired; he ate only when moved by Grace through another’s hands. The mind that asks nothing and expects nothing begins to experience a freedom that no book or technique can give. For Ramaswamy, these vows were not austerities but a natural extension of his Tamil Saiva devotion—a gradual cultivation in renunciation and surrender that slowly reshaped his whole orientation to life. It would become, decades later, the heart of many of his teachings.

On the Rails of South India

In those days, railway personnel considered it an honor to care for sadhus. If a wandering ascetic sat quietly at the station, an attendant would eventually approach with humility: “Where shall we send you?” He would then be escorted onto a train, offered food or milk, and looked after for the length of the journey. When conductors changed mid-route, the departing conductor would personally introduce the sadhu to the next, ensuring his comfort and continued protection.

Ramaswamy rarely spoke on these journeys unless someone asked. Yet as he waited on station benches, people would gather around him with reverence. They would bring fruit or sweets for blessing, sit near him, and listen as he spoke spontaneously about the spiritual life. What we call satsang (spiritual gatherings) were already forming around him. But he did not yet think of himself as a teacher. He was simply a seeker, yet one whose presence already drew others to him.

(Statue of Sri Aurobindo and, inset, in younger years).

The Pull Northward—and the Barrier

All through this period, he felt a call toward the Himalayas, toward Rishikesh, and toward the great sage Sri Swami Sivananda. That longing remained quietly alive in him. Toward 1947, he finally resolved to begin the journey north. But when he reached Calcutta, the country was in political turmoil. Riots had broken out, and all movement north of Benares was blocked.

What he interpreted as an obstacle later proved to be a redirection and one that would enrich his life in unexpected ways.

Pondicherry: Darshan of Sri Aurobindo and The Mother

Uncertain how long the unrest would last, and guided by an inward pull, Ramaswamy traveled south to Pondicherry (now Puducherry) to have darshan of Sri Aurobindo, the renowned philosopher-yogi whose writings were circulating among seekers across India.

Born in 1871, Aurobindo Ghose was a poet, educator, and key early figure in India’s independence movement. But beneath the political fire lay a profound spiritual aspiration. After withdrawing from public life, he devoted himself intensely to yogic sadhana. His consciousness underwent radical transformations, and his writings during this period articulated what he called Integral Yoga—a holistic vision of spiritual evolution embracing all aspects of life.

Sri Aurobindo lived largely in seclusion, giving darshan only four times a year. The Mother, his foremost disciple and spiritual collaborator, guided the outer life of the ashram. Ramaswamy entered an atmosphere of profound silence, devotion, and collective reverence. Darshan at the Aurobindo Ashram was not a spoken event; it was a radiant meeting in stillness. He bowed, received the blessings of Sri Aurobindo and The Mother, and sat in their presence. The encounter was profound and left an enduring imprint.

Though their paths and lineages were distinct, Sri Aurobindo’s spiritual vision carried an emphasis that would later appear powerfully in Swami Satchidananda’s teachings:

- that spiritual realization should not be an escape from life,

- that the Divine can be realized in the midst of the world,

- that all aspects of life—work, relationships, society—can become fields of spiritual practice.

Sri Aurobindo’s Integral Yoga was not structured around formalized practices or a codified sadhana system; it was rooted in an evolutionary transformation of consciousness. While Ramaswamy did not remain in the ashram, he read Aurobindo’s writings and carried with him the insight that the spiritual path is not a turning away from the world, but a recognition of the Divine shining through it. Ramaswamy could appreciate the truth in this world-embracing vision, but he also knew he still needed distance and quiet inwardness before he could live such an understanding more fully. Later, this recognition would become one of the hallmarks of the Integral Yoga he would later share with his students globally.

Clarifying the Two Integral Yogas

Because both traditions use the term “Integral Yoga,” it is helpful to note their differences clearly:

- Sri Aurobindo’s Integral Yoga is a philosophical path of inner transformation, oriented toward the evolution of consciousness and the divinization of life. It emphasizes aspiration, surrender, and the inner guidance of the Divine Shakti, rather than structured yogic techniques.

- Swami Satchidananda’s Integral Yoga, shaped years later within the lineage of Sri Swami Sivananda, emerged as a practical synthesis of Advaita Vedanta and the classical Yoga paths—Hatha, Raja, Bhakti, Karma, Jnana, and Japa—supporting inner and outer harmony and guiding seekers toward Self-realization.

While distinct in lineage and method, both share a common teaching: that the spiritual path is not limited to caves or ashrams but is meant to be lived in the world itself. This resonance made Ramaswamy’s visit to Pondicherry a meaningful waypoint in his journey.

(Illustration of Ramaswamy’s mother in front of his portrait by Ehab Ishwara Aref.)

The Path and Destiny of a Wandering Sadhu

Ramaswamy continued wandering through South India living by his vows for several months. He walked from place to place, receiving what came and resting where he could. The path of a wandering sadhu, with no belongings and no fixed home, was not an easy one for Ramaswamy’s mother to accept.

Srimati Velammai often stood at her doorway wondering where her younger son might be sleeping that night, or who might feed him, or whether he was safe. “We could give him everything he needs,” she would think. “Why must he wander like this?”

“Mother.” She turned around slowly. Ramu had come for a visit. “Oh, Ramu,” she was still crying. “Is it for this type of life I conceived you and brought you up?”

He gently helped her sit down. “What have I done? What I am now is your own wish come true.”

“My wish?” she said. “Was it my wish that you should live in poverty?”

With a playful twinkle in his eye, he teased her the way only a beloved son can. “Who else served all the saints who passed this way? Who prayed for a son just like them? You could have stopped by just serving them alone, but instead you molded my character with their words while I was still in your body. If you had prayed for a worldly son I would have enjoyed myself in the world!”

He raised his arms and dropped them to his sides in mock exasperation. “Mother, you have spoiled my chances for a worldly life! Could I have become anything other than what I am?” She laughed through her tears, touched by the quiet grace of the destiny unfolding through him.