Photo: Original cover of Be Here Now.

Be Here Now remains a spiritual classic for the millions who have read it and will continue to read it. Published in 1971, Be Here Now was written by Ram Dass and the 50th anniversary of the book is being celebrated in 2021. In this article, writer/editor Doug Toft remembers how meaningful this book has been and the pivotal role it has played in his life.

For me, there is life BBHN (Before Be Here Now) and life ABHN (After Be Here Now). And now there is a weird third chapter that I’m learning how to negotiate — life after Ram Dass, the book’s guiding light, who died just before Christmas 2019. I read Be Here Now for the first time in 1972, inhaling most of it in one sitting. Sunlight streaming through a nearby window baked the pages of that homely paperback, and I swear that it started to glow.

The book became a sacred object, and has remained one ever since. When Be Here Now appeared, Eastern spirituality was still considered weird. To meditate or practice Yoga — like eating wheat sprouts or protesting the Vietnam war — was to automatically brand yourself as a member of the counter culture. If you’d told me back then that these practices would one day go mainstream, I would have laughed in your face. Fortunately, I was wrong.

Be Here Now — lovingly self-published, with all its typos and lack of citations — was a love letter that gave me permission to be weird. And I’ve not been alone. Still in print after almost 50 years, Be Here Now has sold over two million copies. Its influence is immense. After Be Here Now you no longer had to scour the shelves in “head shops,” health food stores, and antiquarian bookstores for information about Buddhism, Hinduism, and Taoism. Instead, you could stride confidently into a B Dalton Bookseller (remember them?) or any other major bookstore and find a section openly labeled “Eastern spirituality.” Before Deepak Chopra, before Eckhart Tolle, before Oprah, there was Ram Dass. He, with a handful of others, including Jack Kerouac and Alan Watts launched a cultural conversation that’s still growing.

Life as a “9 to 5 Psychologist”

The first section of Be Here Now — Journey (The Transformation: Dr. Richard Alpert, Ph.D. Into Baba Ram Dass) — is my favorite. This is a page-turning, first-person account of events that have been narrated so many times: Ram Dass’s former life as an academic, his first psychedelic experiments with Tim Leary, his expulsion from Harvard in 1963, and the journey to India that led him to Maharaj-ji [Neem Karoli Baba], his Guru, and his dharma name.

Ram Dass wrote this part of Be Here Now to set the record straight:

“I want to share with you the parts of the Internal Journey that never get written up in the mass media. I’m not interested in the political parts of the story: I’m not interested in what you read in the Saturday Evening Post about LSD. This is the story of what goes on inside a human being who is undergoing all these experiences.”

The story begins with worldly success. As Richard Alpert, Ram Dass had appointments in four departments at Harvard along with research contracts at Yale and Stanford. He owned a Mercedes-Benz sedan, an MG sports car, a motorcycle, a small airplane and a sailboat. And after work he hosted “very charming dinner parties” at his antique-filled apartment in Cambridge. Yet it was all hollow at the center, Ram Dass recalls. Even though he succeeded at “the academic trip,” he secretly saw himself as “a very good game player” rather than a genuine scholar:

“My colleagues and I were 9 to 5 psychologists: we came to work every day and we did our psychology, just like you would do insurance or auto mechanics, and then at 5 we went home and were just as neurotic as we were before we went to work. Somehow, it seemed to me, if all of this theory were right, it should play more intimately into my own life.”

It didn’t work that way, Ram Dass recalls. He got diarrhea before giving lectures, drank heavily, and spent five years in psychoanalysis. When he decided to stop, his analyst told him that he was too sick to quit. “The nature of life was a mystery to me,” Ram Dass recalls. “All the stuff I was teaching was just like little molecular bits of stuff but they didn’t add up to a feeling anything like wisdom.”

Photo: From Richard Alpert to Ram Dass

The Night that Richard Alpert Disappeared

That changed shortly after Ram Dass began hanging out with a new colleague—Tim Leary, who was researching the therapeutic possibilities of psychedelic drugs. In 1961 Leary got a test batch of psilocybin from Sandoz, the pharmaceutical company. On a winter night, he invited Ram Dass and a few other friends (including the poet Allen Ginsberg) to sit around his kitchen table and sample it. When the bottle of psilocybin pills was passed to him, Ram Dass took a 10 milligram dose. After a few hours he noticed that the “rug crawled and the pictures smiled, all of which delighted me.”

Then came a more disturbing vision:

“…I saw a figure standing about 8 feet away, where a moment before there had been none. I peered into the semi-darkness and recognized none other than myself, in cap and gown and hood, as a professor. It was as if that part of me, which was Harvard professor, had separated or disassociated from me. The figure changed several times, cycling through the roles that Richard Alpert played — socialite, lover, pilot, and more. One by one they dropped away, along with his basic identity, ‘that in me which was Richard Alpert-ness.’”

This was scary at first. But after a while he resigned himself to this fate:

“Oh, what the hell — so I’ll give up being Richard Alpert. I can always get a new social identity. At least I have my body….”

But soon his body started to disappear as well. Head, torso, limbs — one by one they vanished until all he could see was the couch on which he’d sat. He panicked, convinced that he was dying. Suddenly a voice sounded inside him, and all it said was ”…but who’s minding the store?”:

“When I could finally focus on the question, I realized that although everything by which I knew myself, even this body and life itself, was gone, I was still fully aware! Not only that, but this aware “I” was watching the entire drama, including the panic, with calm compassion.”

Ram Dass directly experienced an “I” that exists beyond social roles and physical identity. It was a moment of divine joy. Suddenly back in his body, Ram Dass ran outside into the swirling snowflakes, exuberant and laughing all the way. He lost sight of Tim Leary’s house, but “it was alright because I Knew.”

Beyond LSD

This insight persisted long after Ram Dass shifted his focus from psychedelics to yoga, meditation, speaking, writing, and service projects (including fundraising for the Seva Foundation). During a 2012 conversation with Tami Simon, he talked about the 1997 stroke that slowed his speech and restricted his physical activity:

“I think my body got the stroke, and I am in the body,” said Ram Dass, “and there’s no reason to think that I had a stroke. My body had a stroke.”

He was still coming from the place he celebrated during the snow storm — the “I” beyond Richard Alpert and his body, that place beyond life and death. By the time Be Here Now was published, in fact, Ram Dass had already transcended psychedelics. Though he included them in his list of spiritual practices (upayas), he carefully noted their pros and cons:

Pros: Psychedelics can give you a glimpse of enlightenment. This in turn encourages you to keep purifying yourself of attachments via other spiritual practices.

Cons: The psychedelic experience is impermanent. You come down, and you might really bum out. You can also get attached to getting high. And eventually you need to purify yourself of that attachment as well.

“Because the psychedelic agent is external to yourself, its use tends to subtly reinforce in you a feeling that you are not enough,” Ram Dass wrote. “Ultimately, of course, at the end of the path you come to realize that you have been Enough all the way along.”

Cookbook for a Sacred Life

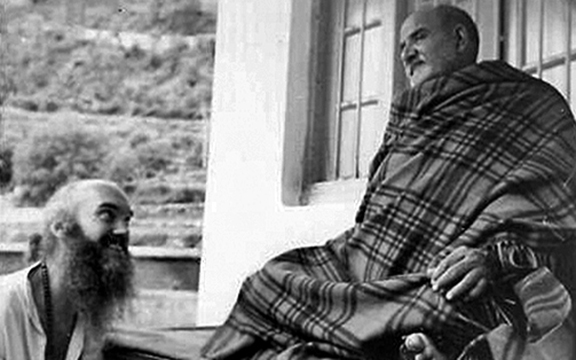

Photo: Ram Dass with his Guru.

In Be Here Now, Ram Dass shot for the moon. In addition to a memoir, he attempted a complete manual for turning daily life into a spiritual practice. And he succeeded to a degree that still surprises me. Consider the section titled Cookbook for a Sacred Life with its headings for: Guru and Teacher, Renunciation, Asanas, Mantra, Transmuting Energy, Sexual Energy, Drop Out/Cop Out, Money and Right Livelihood, The Rational Mind, Time and Space, Dying … and much more.

Some of the suggestions still sound goofy — for example, the idea that advanced practitioners transcend the need for food and can live on light alone. Be Here Now also mentions siddhis — the “powers” that long-time meditators supposedly gain as they increase their power of concentration. “Siddhis,” Ram Dass wrote, “make it easier for you to manifest what you want — money, lovers, or whatever else you desire. The danger is that you create a new train of attachments along the way. And this only reinforces the illusion that you need to get something outside of yourself in order to become complete over time.”

“So, if you do happen to gain powers, just acknowledge them,” Ram Dass wrote. Detach from them and continue your spiritual practices:

“When Jesus said, ‘Had ye faith ye could move mountains,’ he was speaking literal truth. The cosmic humor is that if you desire to move mountains and you continue to purify yourself, ultimately you will arrive at the place where you are able to move mountains. But in order to arrive at this position of power you will have had to give up being he-who-wanted-to-move-mountains so that you can be he-who-put-the-mountain-there-in-the-first-place. The humor is that finally when you have the power to move the mountain, you are the person who placed it there — so there the mountain stays.”

Stay Grounded, Be Kind

Ram Dass also urged spiritual practitioners to live responsibly in the material world — to manage money, take care of the household, and be a dependable family member.

“Just because you are seeing divine light, experiencing waves of bliss, or conversing with Gods and Goddesses is no reason to not know your zip code,” he wrote. And in a time of deep partisan divisions, Ram Dass’s pleas to let go of an “us versus them” mentality sound remarkably fresh:

“Thus, the rule of the game that everyone work on himself in order to find the center where ‘we all are’ within himself in order that he can meet with other human beings in that place…. You may disagree with all his values, but behind all of them … HERE WE ARE … all manifestations of the Spirit.”

About the Author:

Douglas Toft has been a professional copywriter and editor since 1979. Over the years he freelanced for Cengage Learning, Houghton Mifflin Company, Hazelden Publishing, Mayo Clinic, United Healthcare, and other organizations and individuals. Since 1989, he’s been the contributing editor for the Master Student Series of books published by Cengage Learning. He has also coauthored five books. For more information, visit douglastoft.com

Douglas Toft has been a professional copywriter and editor since 1979. Over the years he freelanced for Cengage Learning, Houghton Mifflin Company, Hazelden Publishing, Mayo Clinic, United Healthcare, and other organizations and individuals. Since 1989, he’s been the contributing editor for the Master Student Series of books published by Cengage Learning. He has also coauthored five books. For more information, visit douglastoft.com