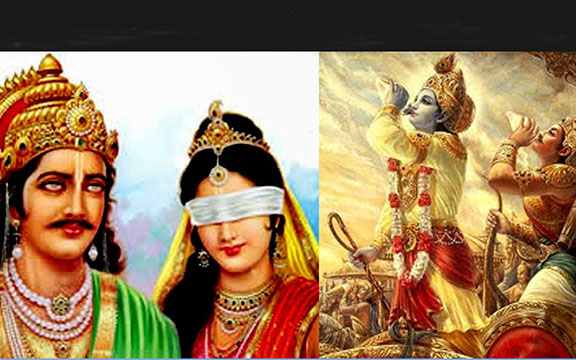

Photo: Dhritarāśhtra and Gandhari; Krishna and Arjuna.

In part 4 of this series, we talked about Dhritarāśhtra, the blind king. We can consider him to be manas, the lower mind. And we also talked about Sanjaya, his minister, who we said could be considered our conscience. The king is blind, but he is not deaf. He does want to hear Sanjaya’s input. It’s always a good sign, though maybe rare, when the lower mind asks the conscience to speak up. However, the problem is that upon receiving the input, it is not unusual for our blind ruler to either ignore the input or distort it.

When the ministers were looking for a partner for Dhritarāśhtra, not that many princesses from the neighboring kingdoms were interested in marrying a blind man. Gandhari was okay with it, but she did something unusual. She blindfolded herself so that she wouldn’t have any advantage over her husband. So Gandhari has the capacity to see, but she marries the blind king and chooses to give up her sight.

Gandhari can be considered our buddhi, our inner intelligence. If Gandhari marries the blind king, then four things tend to happen:

- Our intelligence is used to rationalize the benefits of the status quo and why it is dangerous to move outside the boundaries of the known.

- Our intelligence is used to keep the mind moving outward through the senses.

- Our intelligence is used to keep us away from the present moment.

- Our intelligence is used to sabotage our spiritual journey. Because of our blindness we tend to shoot our soul in the foot.

For decades the Bhagavad Gita has been a guide and inspiration in my life. Working on a translation of and commentary on the Gita has enabled me to dive deep into this sacred, living text. Recently, I was working and reflecting on the 18th chapter, the 31st verse. It reads like this: “When the buddhi is rajasic (restless), it has a distorted and confused understanding of dharma and adharma, what’s good for the soul and what puts more obstacles to the soul. Therefore, it often errs in deciding what to do and what not to do.”

The interesting thing that happened to me was while I was working on this verse, I heard the ping of an email arriving. And I normally wouldn’t interrupt this work, but I saw the name of the person, and I said, “Hmm, I would like to see what’s happening.” So I checked the email. And the person was saying I could have done something better and gave me some advice about how to do that. My mind really got worked up, with vrittis flying all over the place. My samskaras presented me all kinds of options about how to react or respond.

Suddenly it struck me that I was supposed to be working on the Gita book. And then a second bolt of lightning struck, and I realized that I just got this amazing lesson from the Guru and the Universe! How easy it is for my buddhi to veer into rajas. As the verse said, when the buddhi is disturbed, it doesn’t know what to do or how to distinguish between dharma and adharma. I’m grateful for such a timely and immediate lesson!

My homework for this week: Recognize when my samskaras, with their pre-conceived notions, are clouding my judgment and pushing me to do something that I am likely to regret later. I invite you, as always, to join me in this homework. Om Shanti.

About the Author:

Swami Asokananda, initiated into monkhood in 1973 by Sri Swami Satchidananda, is the spiritual director of Integral Yoga Institute of New York, co-director of the Integral Yoga Global Network, and one of Integral Yoga’s foremost teachers. He is the primary instructor for the Intermediate and Advanced Hatha Yoga Teacher Trainings offered around the world. He has deeply studied the Bhagavad Gita for many decades and is currently writing a commentary.

Swami Asokananda, initiated into monkhood in 1973 by Sri Swami Satchidananda, is the spiritual director of Integral Yoga Institute of New York, co-director of the Integral Yoga Global Network, and one of Integral Yoga’s foremost teachers. He is the primary instructor for the Intermediate and Advanced Hatha Yoga Teacher Trainings offered around the world. He has deeply studied the Bhagavad Gita for many decades and is currently writing a commentary.