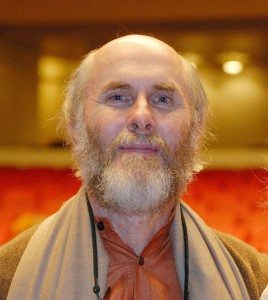

Dr. David Frawley is regarded as one of the world’s foremost experts on Ayurveda, Yoga and Vedic Studies. In this article, he offers an overview of the relationship between the teachings of Yoga and the Bhagavad Gita. He also discusses the Gita’s teaching of Yoga as an inner sacrifice.

Dr. David Frawley is regarded as one of the world’s foremost experts on Ayurveda, Yoga and Vedic Studies. In this article, he offers an overview of the relationship between the teachings of Yoga and the Bhagavad Gita. He also discusses the Gita’s teaching of Yoga as an inner sacrifice.

Integral Yoga Magazine: In your view, what is the relationship between Yoga and the Gita?

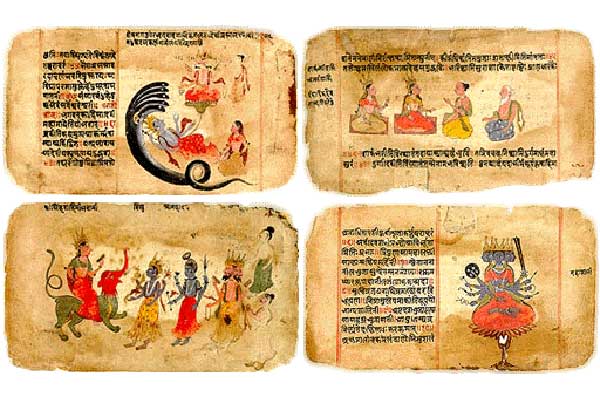

David Frawley: The Gita is a Yoga Sastra (foundational text) containing teachings on Karma Yoga, Bhakti Yoga, Jnana Yoga, Prana Yoga and so forth. It teaches Integral Yoga—to use Swami Satchidananda’s term—meaning, it looks at Yoga from many sides. It’s the main text one would want to study in the broader sense of antaranga or inner Yoga. If there is a scripture of Yoga it is the Gita. The Yoga Sutras of Patanjali is more of a technical work. You can use the Gita to understand the Yoga Sutras.

The Gita is said to be the essence of the Upanishads and gives Upanishadic approach to Self-realization. It contains the whole Sankhya Yoga philosophy in the thirteenth chapter. In the sixth chapter, the Gita defines Yoga as meditation and Self-realization, just as does the Yoga Sutras. Without knowing Sanskrit many of the similarities get translated away.

“Yoga is a means to disconnect your identification with that which experiences pain. Therefore, be determined to steadily practice Yoga with a one-pointed mind.” 6.23

There is a lot of correlation between the two texts. The Gita, while using a richer language than the Sutras, uses all the basic terms we find in the Sutras. The Gita also employs Vedic metaphors such as the fire of Yoga, fire of meditation, fire of Brahman; philosophical terms such as Atman and Brahman, and it gives a human personality to the teachings (Krishna). The Gita is only one portion of the Mahabharata, the larger epic dealing with the subject of Yoga. There is also the Moksha Dharma Parva, which is another section of the Mahabharata that is longer than the Gita and in which Bhishma is the teacher.

IYM: What is the central message of the Gita?

DF: The Gita contains everything of relevance to the spiritual path. It is also about the psychology of mind. Psychology is part of Yoga because we have to understand the chitta (mind-stuff) in order to attain Self-realization. The Gita teaches us how to fight with equanimity and detachment in the battlefield of life. The Gita’s main concern is in bringing peace, happiness and harmony to mind, heart and soul. It also contains a lot of teachings on Karma Yoga, the Yoga of selfless action.

IYM: How can Yoga teachers make the Gita more accessible for their students?

DF: First, we have to stop being ashamed of our Yoga tradition and philosophy. Any discipline has technical terminology, a way of understanding the universe, a philosophy. You can’t teach Buddhism without its cosmology or philosophy. Yoga teachers should be trained in Yoga philosophy. Yoga was meant to be for people with inquiring minds. It’s a way of organizing the mind. The Yoga scriptures aren’t reflected in the popular western Yoga, because they are not commercial. Yoga is now a thirty billion dollar industry! I recently read a definition of “LA Yoga”: asana plus shopping! [Laughs] But it is true that Yoga centers make more money in their boutiques than in their Yoga classes.

IYM: Do you think the expression of devotion towards Krishna in the Gita is an obstacle for those trying to practice a more secular Yoga?

DF: It’s very interesting because, in the Yoga Sutras, Patanjali emphasizes Ishwara pranidhana (surrender to God). Though the Yoga Sutras is a non-sectarian text, in which Patanjali suggests one can approach Ishwara by any name or form, Patanjali himself was a devotee of Krishna. We can study the Gita as a philosophical text or as a devotional text. We can approach the Gita without devotion to Krishna and see Krishna as an exponent of the teachings, an ideal teacher or representative of Brahman. For those who are not comfortable with the idea of Krishna as a personal deity, Krishna may also be understood as representing Brahman and Atma. The Yoga of knowledge (Buddhi Yoga) pervades the entire Gita with its Vedantic philosophy. Brahman nirvana is the goal; realizing the Atma is the goal, and Krishna can help the seeker in that process.

The Gita is teaching Upanishadic ways of knowledge from meditation on the Self to realization of the Purusha. You don’t have to accept Krishna as your Ishta Devata to study the Gita. It is widely known that Krishna is the dominant teacher for many Hindus who are not followers of Krishna. Abhinavagupta, the main teacher of Kashmir Saivite tradition studied and wrote a commentary on the Gita. Sri Ramana Maharshi had his students study the thirteenth chapter as the essence of the Gita. So, it can be approached by various sides.

The Gita is not about blind devotion. It’s a path of Yoga. While Ishwara pranidhana is a key teaching of the Sutras, it is elaborated upon more in the Gita. It explains bhakti (devotion) in a very methodical way as a means for gaining realization of the divine and the inner Self. The practices are as much about mantra, meditation, chanting and puja as devotion to Krishna.

IYM: Does the relevance of the Gita for Yoga teachers boil down to whether one is interested in practicing Yoga as a spiritual path or mainly for exercise?

DF: Yoga is essentially a path of Self-Realization, moksha, transcendence of suffering, going beyond rebirth. Asana is not a major part of traditional Yoga. It plays a part in one’s preparation for meditation. There is a distinction between inner (antaranga) and outer (bahiranga) Yoga. Bahiranga Yoga is mainly asana, pranayama and pratyahara (control of the senses). Antaranga Yoga is meditation and samadhi (superconscious state). The Gita is more concerned with inner Yoga and all of classical Yoga is concerned with the same. Many Yoga teachers and students are not even aware that the traditional text of Hatha Yoga, the Hatha Yoga Pradipika, talks more about pranayama than asana. It addresses three main topics: asana, pranayama (breathing practices) and Raja Yoga/samadhi. One-third of this text is devoted to Hatha Yoga and even within that section, yogic diet and other practices are discussed. The largest section is on Raja Yoga section and Hatha Yoga is presented as the Yoga of personal effort toward the goal of samadhi.

IYM: Chapter Four of the Gita addresses inner and outer sacrifices. Can you comment on this and its relevance in modern life?

DF: Yoga arose as an inner sacrifice, the offering of the prana (energy) of speech and mind into the divine light within us. This is how Yoga is defined originally in the Upanishads. We live in a world of consumerism. According to the Hindu or Indian order of life, we exist to give. Our duty is to give. In the modern world, we believe it is our right to take, each man and woman for himself or herself, but the Indian life is all about dharma: you exist for the benefit of the universe. The outer sacrifice is a ritual or way to teach that to people.

We learn by giving—giving offerings to deities, animals, ancestors and so on. Happiness comes by making offerings to others rather than getting what we want. Yoga was the inner sacrifice in which people offered their speech, energy and mind through pranayama, mauna (silence), pratyahara (control of senses) and control of the mind. When you offer your prana into the divine, it’s a way of transforming it. Classically, Yoga was done as a sacrificial offering to the higher reality. Through sacrifice and by tapas (austerity), we can reach a higher level.

Even in ordinary life, to achieve great things, we have to discipline ourselves. If I want to become a great musician, I have to have good discipline, dedication, do a lot of work and offer myself into the fire of music. Spiritual practice also needs discipline and the goal is not achieved overnight!

IYM: Would you give us some practical examples of how we can practice inner and outer sacrifice?

DF: If you are practicing pranayama and you notice a thought arising: “I don’t like so and so.” You can mentally offer that thought into the fire of prana through your conscious pranayama practice. You can offer unwanted or disturbing thoughts into the fire of meditation. Burning up karmas requires the fire of knowledge.

Homas and yajnas (sacred fires) are not just outer rituals or sacrifices. They purify the psychic atmosphere. You are offering essences such as fragrances, oils, resins, ghee, camphor and herbs to create aromas and fragrances that purify the individual and collective mind.

IYM: Do you have any closing thoughts on how one should approach the Gita?

DF: Look at the Gita directly. Don’t get caught in modern translations. You can read verses yourself. Honor the commentaries, but read it for yourself. The Yoga Sutras need commentary, but the Gita doesn’t necessarily.

From an Interview with Dr. David Frawley (Pandit Vamadeva Shastri)

Dr. Frawley is Founder and Director of the American Institute of Vedic Studies and the author of thirty books, several training courses and over a hundred articles on Vedic systems of knowledge. He has taught extensively in the U.S. and Europe and is highly regarded in India as a Vedic teacher. For more information on Dr. Frawley’s courses and publications, please visit: www.vedanet.com.

Dr. Frawley is Founder and Director of the American Institute of Vedic Studies and the author of thirty books, several training courses and over a hundred articles on Vedic systems of knowledge. He has taught extensively in the U.S. and Europe and is highly regarded in India as a Vedic teacher. For more information on Dr. Frawley’s courses and publications, please visit: www.vedanet.com.