Narada Burton Greene (Photo credit: Johan Janssen)

In December 2020, pianist Narada Burton Greene was interviewed by All About Jazz, a web site produced by jazz advocates, jazz professionals, and web technicians. This article is an excerpt from that in-depth article that traces Greene’s history and evolution as one of the great jazz avant-garde veterans. He also has been a longtime student of Swami Satchidananda and in this interview he talks about this influence on his life and music.

“If I have tried anything in the music – it was always about trying to contribute to the universal consciousness. So that’s what I’m working on. I’m trying not to get disturbed by the so-called ups and downs. I try to bring that quality out in music wherever I can.”

—Burton Greene

Chicago-born pianist Narada Burton Greene (b.1937) can be called a veteran of the 1960s jazz avant-garde—the starting point of his universal musical life. In 1962, he moved to New York and founded, together with bassist Alan Silva, the Free Form Improvisational Ensemble, which played improvised music without preconceived compositional elements. In 1965, he became a member of the Jazz Composers Guild, founded by Bill Dixon and Cecil Taylor. The Jazz Composers Guild resonated with the community spirit that Greene had grown up with through his father’s social-democratic family tradition. But the communal project lasted only six months. Disgusted with the materialistic “American dream,” that lacked an understanding of community and experimental art and quickly turned a free artist’s life into a precarious existence, he moved to Europe in 1969, where he worked with John Tchicai and Willem Breuker, among many others. Since 1986 he has been living on his own houseboat in Amsterdam. Greene’s free improvisational approach is open to eminently heterogenous musical languages that he touches on with his different band projects, and also when he plays solo piano—from jazz to the bitonal music of a Béla Bartók, Igor Stravinsky and Charles Ives, the music of Karl-Heinz Stockhausen and right up to Indian ragas, klezmer, Sephardic, and Hasidic music.

All About Jazz: Can you describe the atmosphere you grew up in, also in terms of music?

Burton Greene: My mother was a classical music teacher. During The Great Depression she was teaching in New York, where she met my father in the late ’20s. They got married just at the time of the beginning depression. She was teaching piano at that time. She had studied with Walter Damrosch, who was a famous conductor, at Columbia University. My father was selling eyeglasses from Europe and New York. They moved to Chicago in the early 1930s. My father’s people were Greenbergs, not Greene. My father had shortened his name, to sell the eyeglasses to the optical trade. People loved the eyeglasses but didn’t like his long nose. There was lots of antisemitism at the time, especially in small towns in the Midwest. My parents had a small attic flat without hot water and my mother was pregnant with my older brother. My father was getting desperate to sell his glasses. When he told one optometrist his name was Greene, the optometrist said: ‘Oh, then you could be related to the English Greenes?’ He got his first order and more to come. So, then he could afford a real apartment, and finally, in 1941, they had a small house built on Drake Avenue on the North side of Chicago, where I grew up. My mother had a small baby grand piano in the living room. At five years old, I was hearing all this great boogie-woogie—this was early ’40s.

AAJ: When did you decide to become a professional musician?

BG: I was always into music. And I had to do odd jobs to stay alive. After a couple of years in college I had enough. I wanted to get out and learn about music. But I had to do odd jobs. I sold insurances, stupid things. At 25 I decided, whatever happens to me, whatever stupid jobs I’m gonna have to do, I want to be a professional musician. I don’t care about having not a penny, I love music. In the middle of 1960 I went to San Francisco, I was 23. After a year and a half, I went back to Chicago for some months and then I went to New York.

AAJ: In New York you developed The Tree System of Tonality, as you called it.

BG: Yes, exactly. I composed this piece “Tree Theme,” which has the trunk and the roots in A minor, then you get into the branches, which are already bitonal. So, if you start in A minor, maybe you modulate, go to A flat and then to B flat with A flat on the bottom, and further, more freely, intuitively. So, you’re getting into bitonality, of which I heard so much beautiful music like Bartók, Stravinsky, Charles Ives. I was very much influenced by that stuff.

AAJ: Going from Bartók and Stravinsky for instance, you developed your own system of tonality?

BG: Yeah. You develop that and by the time you get to the small branches and leaves, you get into so much abstraction, pantonality. Afterwards I recapitulate the theme in A minor, bring it back home.

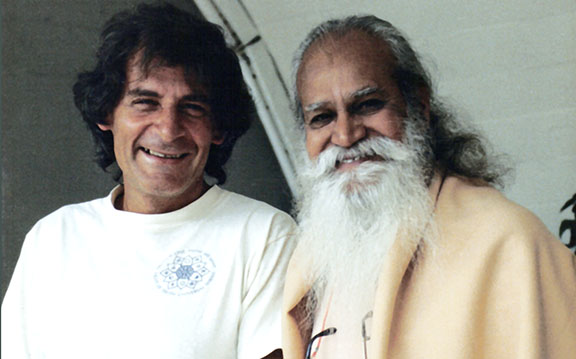

(Photo: Narada with Yoga master Swami Satchidananda, Lucerne, Switzerland, 1980s.)

For me, music is part of the universality. Through music I can link everything up to Yoga, meditation. The whole universal thing is all connected. It’s called sanity versus insanity. We need to live by basic holistic methods of living, having real food on your table, a nice place to live, that’s it: one car or whatever, basic needs, taking care and making room for our brothers and sisters. Otherwise it’s all a big show: ego power games, excess money, manipulations, selfishness, insanity! I have always made no more than about 20.000 [dollars] a year. So, I’m so-called “below the poverty line.” But indeed, over the years I got a nice houseboat, a 25-year-old car that runs like a train, what more can I want? Now I have a recent model grand piano. It’s possible living on even low money. And yet I even have to throw stuff out all the time, give it to charity, so I have room to live!

AAJ: You decided to move to Europe.

BG: I was in Paris first of all. That was great. A whole lot of musicians came over and we met each other. I didn’t know some of them until I was in Paris—like the AACM who were also from Chicago. A lot of gigs, a lot of stuff happening, it was wonderful. I came to Europe with forty dollars. I was able to hitchhike to Paris, went to an Arab bar on the right bank of Paris, where you get the cheapest coffee. Then I ran out of money after two days, I had my last café crème and I passed out on the floor at the bar. Algerian workers felt sorry for me, they saw that there was somebody on the floor, they took me into their flat. I woke up two days later, they gave me tagine and couscous and I felt really good. When I hear about the problems between Arabs and Jews I say, don’t tell me about this, the Arabs and the Jews have been together for five thousand years. It’s the politicians, they are making this enmity.

AAJ: How long did you live in France?

BG: For six months. After that, I first was in Denmark to play with John Tchicai. I loved Denmark, I loved Copenhagen. So, I had to choose. I said, I’ll not go back to Paris, it’s too nervous and too expensive. But I enjoyed the contact with all the great musicians in Paris. So, after that I wrote a couple of pieces for the radio orchestra in Denmark.

But all the crazy stuff that had happened came on me and I had a nervous breakdown, there in the garden house. It took me two or three months to get myself back together slowly. I couldn’t walk for about 3 weeks. My lower back was frozen, the nerve ends. I gradually came back and then things started to happen. The ’70s were great in Amsterdam.

AAJ: Around that time, you went to India.

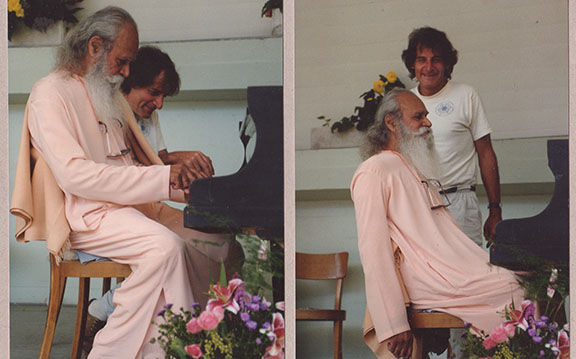

(Photo: Improv session with Swami Satchidananda, Lucerne, 1980s.)

BG: Yeah. Obviously, this was part of my healing process. I took a 4-month trip as part of the Yoga group traveling with our teacher Swami Satchidananda, a deep meditative Yoga experience in India and Sri Lanka (1970-1971). The Yoga was slowly beginning to get me more together. I had met my teacher in 1967 and started doing Hatha Yoga for some months before getting my meditation mantra initiation from him at the end of that year. Thanks to Yoga over the years it helped me put back all the pieces into a more peaceful existence. We all exploded with such a dynamic music in the ’60s, but unfortunately most of my contemporaries are gone, because they never found a way to put back the pieces. I gradually went from an atomic bomb to an atomic balm!

AAJ: Can you share some details about your musical connection to the Indian ragas?

BG: I met sitarist Jamaluddin Bhartiya from Jaipur, India in 1973. I knew his student here, sitarist Darshan Kumari. She organized a lot of Indian music concerts here in Holland. She brought Bhartiya here and I became his student. We were the East West Trio. I realized that the Indian tradition—great music that always existed and always continues to exist—has to be done with original flair and not by copying or imitating it. The idea of the East West Trio was to bring the jazz idea into the raga. And also, we had this great bongo player during that time, Daoud Amin. He is a Puerto Rican from New York and he brought his Latin rhythms into it. So, it’s a fresh world music the way we did it. Daoud is not on the records we made, he already left town. Instead we got Glenn Hahn from Suriname. He brought that same idea with bongos and congas and other percussion things. He’s gone unfortunately, died quite young.

AAJ: When did you start playing klezmer music?

BG: At the end of the Eighties. When I was about 52, I met this young Jewish kid named Yiftach Bar, a musician who came by and said: ‘We heard about you and your music.’ He brought along a friend, who was interested in what I was doing too, and they said, can you play us some of your music? I was already on my houseboat. I played them some of my music on records. And then Yiftach said: ‘That’s nice, jazzy, but what’s your music?’ He was a nineteen-year old kid. I got a bit peeved and said: ‘Listen man, that’s my music, what are you talking about?!’ ‘No, this is your music.’ He played some beautiful stuff from clarinetist Giora Feidman. Giora is the guy who played so beautifully on the score of the movie Schindler’s List, so poignant. John Williams, the guy who wrote it, worked with Steven Spielberg and the big Hollywood guys. He wasn’t Jewish, but he really got it, the feel of that music. So, these cross references of different cultures are very interesting. People transcend their own cultures and get into other cultures. They really live it, you know.

AAJ: Do you have the feeling that you are closer now to yourself with the music you are playing today?

BG: Yeah, otherwise I wouldn’t do it. It transcends descriptions, it has traditional blues and bebop elements, it has Indian elements, it has Jewish elements, it has Arab elements, all kind of stuff.

AAJ: Can one say that your Jewish background is just a part of your universal musical language.

BG: Again, going back to the Tree Theme. The roots might be anywhere but it grows and spreads out to everywhere, so we are all connected. You cannot diss anybody. If you do that you diss yourself.

AAJ: But it was and is important for you to go back to your family roots.

BG: You should know where you come from, know your ancestry, know your history. Without that you don’t know where you are going. You have to be rooted somewhere before you can have branches and leaves. Trees live thousands of years because they have these wonderful roots and expansion. This is the way we come to universality too.