Photo: Ranger on Cape Cod at Sunrise.

In this new column for Integral Yoga Magazine, “Gita in the Garden, Living Yoga in a Busy World,” Yoga teacher Gita Brown shares her reflections on, well, living your Yoga. In each installment, she will share what her Yoga study and practice has revealed to her about living Yoga in an embodied way and amid the challenges of modern life. She begins with lessons from her dog, Ranger.

Ranger nuzzled my hand. A brisk autumn wind blew around the barn. His cold nose interrupted my list-making: cut down the sunflowers, mulch the asparagus, replace the bunny-eaten spinach. At one hundred pounds he could have knocked me over. But he waited. I felt he was connected to something more than a romp through the woods; he seemed to ask if I had the courage to be present here and now. Each time my steps on the spiritual path faltered, Ranger challenged me to remain steady.

Nine years ago he came galloping into my life. I had just turned forty and was living in a cottage in the woods in coastal Massachusetts. I was on leave from my job as a music therapist and Yoga teacher as I healed from an injury. I had been working with a young man with special needs and he had become agitated and punched me. My jaw was severely sprained and whiplash rendered my neck almost immovable. I had no animosity towards my client; he was unable to communicate his needs and I can only imagine how the frustration of twenty-five years of not being able to speak had built within him.

My husband and I picked up Ranger a few weeks after I was injured. I was still eating liquids and popping anti-inflammatories to keep my migraines to a dull roar. At eight-weeks-old he seemed to be made only of floppy paws. When we drove away he cried so loudly I had to take him out of the crate and hold him. He quickly fell asleep in my arms. As his head draped over my elbow I woke up to the possibility of the moment.

Photo: A snooze among best friends.

That spring I had become fixated on making improvements to the perennial beds; especially by adding trellises on which the star-shaped clematis flowers would bloom. Ranger was on a leash that was tied to my belt. He poked his snout into the daffodils. Each time I bent over a shock of pain jerked my neck. After a half-hour my frustration grew and I threw a piece of the trellis across the yard and fell to my knees. Ranger came over and climbed up my lap to lick my face. I tapped my ear; I was training him to “kiss” on command by giving my ear a gentle lick. He gave my ear a quick thwip with his tongue. I sighed and massaged my neck. Sunlight illuminated Ranger’s black coat. His head began to droop. He slowly crumpled and fell asleep across my feet.

At forty, I had over two decades of experience with Yoga. But I had one foot in spiritual discipline and the other in the culture of achievement. Healing was something to be accomplished; another step on the treadmill of success. But as Ranger’s paws twitched in his sleep and the sun warmed our necks I gave in. I reclined and joined Ranger for a nap. For the rest of that spring I gave up “accomplishing” healing. The clematis gradually climbed the trellis. Being on the spiritual path is informed by the word spirit; from the Latin spiritus. As Benedictine monk Brother David Steindl-Rast says, spirituality “is aliveness on all levels. It must start with our bodily aliveness.” Ranger was alive in his body; and he was helping me to wake up to mine.

When he turned two, his breeding as a protection dog switched on. He had grown into ninety-five pounds of muscle. He also overreacted to any perceived threat. When he was a pup he usually slept through trips at the Starbucks drive-thru window; now he lunged, barked, and snapped until the barista fled in fear. We started working with Mike, a trainer who was experienced with protection dogs. Mike was as brusque as his crew cut. His motto commanded from a sign in the training room Train, Don’t Complain. Mike began to teach us and as we improved he had me add distractions. “Don’t say your dog does everything great except if he sees a squirrel. There is no unique distraction—either he’s trained or he’s not.”

So we took our training on the road and went to pet stores and harbor walks. People would slow down their cars and say “Great dog! Can I take a picture?” But my heart would race when people approached. Ranger was aggressive and I was terrified that he’d jump and knock them down. I looked confident but my hands trembled. Ranger sensed my anxiety through the leash. He would obey but would snap and whine. Breakdown felt a moment away.

One day Mike brought his German Shepherd into the room. As usual my nerves ran down to my fingers. Ranger’s hackles began to rise. Mike had told me a million times to keep my hands relaxed. But I began lifting my hand as we walked in heel. Mike whacked my arm down. “Keep it down,” he said, “be steady.” I was shocked into clarity. I had been “performing” my calmness. Ranger was tuned into who I really was, not who I pretended to be. I started taking deep breaths when strangers approached. I trusted the training, him, and me. Ranger calmed.

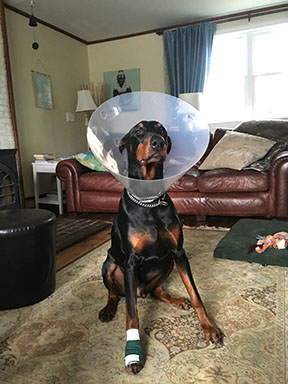

Years passed and the clematis vine pushed into full flower. We outgrew our cottage and we moved to an 1850s farmhouse that we call Three Dog Farm. Along with Ranger we had two more dogs, Zoë and Rosie. We also had acres of land and enough room to garden for food, for the beauty, and for the wild things. Ranger was now a calm adult. Visitors to our house called him regal and a gentleman. One day at a cranberry bog Ranger cut his paw on broken glass. The wound required seven stitches and a plastic paw covering for when he went outside. It also shut down his daily off-leash runs. After a month the gash was still not healed so the vet recommended another month of the leash and paw covering.

Photo: Ranger healing from his injury.

The next morning I was in a rush. Ranger stood patiently as I tried to wrap the plastic around his paw. But my antsy fingers couldn’t tie the string and it kept slipping. I wanted to rip the plastic bag in pieces but instead dropped it and yelled Rats! Ranger hung his head. I felt wretched. Walking on a sore paw and not being able to run with the vigor of his wolf ancestors must have felt punitive. I retrieved the plastic bag. I steadied. He lifted his paw so I could tie it on. When I got it in place he gently licked my ear.

Spiritual discipline is just like that. It is the constant practice of being present; of remaining steady through the fluctuations of events and emotions that we think define our selves. As the sage Patanjali wrote in The Yoga Sutras: “Practice becomes well established when attended to for a long time, without a break, and with enthusiasm.” Step by step that spring, Ranger’s paw healed.

A few years later Ranger paced in the dog run and whined to be let out. The garden drooped under heavy frost. Three years had passed since we moved to Three Dog Farm and our garden had grown to ten raised beds and a chicken coop. When I opened the gate Ranger darted between the frosted chrysanthemums and into the woods. The maple trees were burnished with yellow. My nose tingled with the scent of woodsmoke. My feet dragged up the hill; my mind full of the million things I felt I just had to do that morning. Ranger plunged through the brush in excitement; the rut—deer mating season—had begun and the woods were alive with the scent of creation. I churned over my to-do list and hurried up the last rise of the hill. I was lost in my thoughts and tripped. By grace—or maybe thirty years of Hatha Yoga—I didn’t fall. My feet skittered through the pine needles and I stumbled to a stop. Ranger galloped over and sat in perfect heel position.

“Wow little buddy,” I said. “If a yogi trips in the forest and no one is there to see it, is it still funny?” He nuzzled my hand. I scratched behind his ears. Under the woodsmoke lay the scent of aromatic pine. Overhead a chirpy gang of tufted titmice fed in the treetops. I had nearly fallen in front of a silver birch tree I called my “Prayer Tree.” I looked up at the double-toothed leaves as the sun illuminated them to a brilliant yellow. “Ninety-three million miles that sunlight has traveled, Ranger-roo. Crazy, huh?”

He prodded my hand to keep scratching his ears. We stood and became infused with the sun and connection of the universe. This sun—a 4.5 billion-year-old yellow dwarf star—sent us energy waves in the electromagnetic spectrum. These energy waves of visible sunlight illuminated the leaves and powered photosynthesis. The gravity of the sun also holds our entire solar system together; bringing everything from the planets, space debris, and the earth—including Ranger and I—into orbit around it. How could I be anything other than amazed at this unity of the universe. Eventually Ranger and I broke our reverie and wandered back home.

Now I’m almost fifty and have known Ranger for almost a decade. He still runs like a deer—although his arthritis sometimes makes him stiff. We still walk every day. He graces me with countless opportunities to become alive. If Brother Steindl-Rast said, “Spirituality…must start with our bodily aliveness,” then I have to think that Ranger is onto something with his nudging. Tending to our animal selves—our need for safety, sleep, food, water, connection—heals the division between ourselves and our spiritual lives.

Rather than false divisions of God or man and science or false faith, we are invited to experience that spirituality is present in all things. The whole of the universe expresses itself as individual waves; as dwarf stars and birch trees and Doberman Pinschers. Walking with a dog can give us the “bodily aliveness” that will point us to the very ground source of our being; the Cosmic Consciousness that is all things, the One playing as the many. Our suffering comes when we deny this connection and feel that we are separated and alone. We long to remember we are whole so we create connection with work, food, drugs, money, or relationships. Instead, we can remember that the nudge of a Doberman’s nose is a reminder to become alive—to embody spiritus.

Brother Steindl-Rast and Sri Swami Satchidananda were longtime spiritual brothers and collaborators in interfaith activism. With Brother David’s assertion that we can come alive as a form of spiritual awakening, Sri Swami Satchidananda also added, “A real spiritual experience means to see the unity in diversity. See the same spirit in everything. Be gentle…be loving. See your own Self in all and treat everything properly.”

When Ranger and I next walk it will look like a woman and her dog strolling under the pines. But if I take Ranger’s presence as a doorway to spirit, then perhaps I will feel my “own Self in all” and experience the greatest gift a dog’s love can provide: a connection to the spiritual aliveness and oneness that is the miracle of our existence.

About the Author:

Gita Brown is a wellness activist, musician, and writer. She is a certified Advanced Integral Yoga® teacher and licensed Yoga for the Special Child® practitioner. Through her “Yoga with Gita courses” and podcast, “The Gita Brown Show,” her mission is to teach her students how to adapt the traditional practices of Yoga to bring more ease, wellness, and joy into everyday life. Gita started Yoga as a teenager, when her love of Yoga grew in tandem with her career as a classical clarinetist and music therapist. For three decades, she has taught Yoga, wellness, and music courses at colleges, schools of music, community schools, private studios, public schools, and hospitals. She is currently finishing final revisions to her memoir. The story is about how she repurposed her wedding vows into a yogic vow to live love as a way of life—a pilgrimage that endured even as her husband and childhood sweetheart battled end-stage alcoholism. She offers Yoga to students of all ages and abilities through online programs and in person at her home studio at Three Dog Farm in Kingston, Massachusetts. Learn more about her services by visiting: https://www.gitabrown.com

Gita Brown is a wellness activist, musician, and writer. She is a certified Advanced Integral Yoga® teacher and licensed Yoga for the Special Child® practitioner. Through her “Yoga with Gita courses” and podcast, “The Gita Brown Show,” her mission is to teach her students how to adapt the traditional practices of Yoga to bring more ease, wellness, and joy into everyday life. Gita started Yoga as a teenager, when her love of Yoga grew in tandem with her career as a classical clarinetist and music therapist. For three decades, she has taught Yoga, wellness, and music courses at colleges, schools of music, community schools, private studios, public schools, and hospitals. She is currently finishing final revisions to her memoir. The story is about how she repurposed her wedding vows into a yogic vow to live love as a way of life—a pilgrimage that endured even as her husband and childhood sweetheart battled end-stage alcoholism. She offers Yoga to students of all ages and abilities through online programs and in person at her home studio at Three Dog Farm in Kingston, Massachusetts. Learn more about her services by visiting: https://www.gitabrown.com

Photos courtesy of Gita Brown.