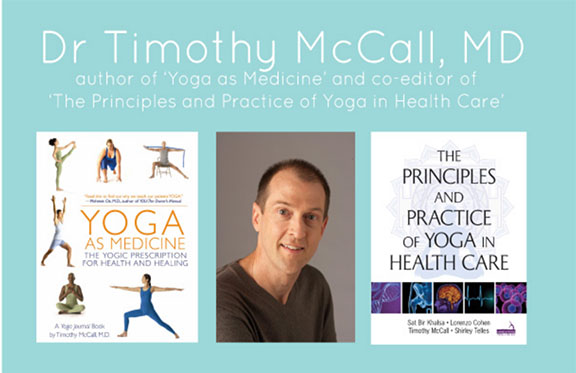

Timothy McCall, M.D. is the author of Yoga as Medicine and an editor of Principles and Practice of Yoga in Health Care. During an Integral Yoga Teachers’ Conference, Dr. McCall shared the results of his exploration of Yoga research in India. Here is an excerpt of what he shared:

Timothy McCall, M.D. is the author of Yoga as Medicine and an editor of Principles and Practice of Yoga in Health Care. During an Integral Yoga Teachers’ Conference, Dr. McCall shared the results of his exploration of Yoga research in India. Here is an excerpt of what he shared:

One of the most surprising I learned was that Indian Yoga research is more advanced than Western research. It is quantitatively and qualitatively different. The research in the U.S. is almost entirely asana-based. For example, one of the most well-know n studies (other than Dean Ornish’s work) is by Marian S. Garfinkel on the effect of using asanas for carpal tunnel syndrome.

My first stop was the research center at the beautiful Swami Vivekananda Ashram outside of Bangalore. They do more Yoga research than any place in the world. There was a study going on while I was there of women with breast cancer. They took 200 women, randomized into a group to get chemotherapy, surgery, radiation plus Yoga or the same three things plus a social control meant to mimic some of the human interaction that might explain some of the effectiveness of the Yoga intervention.

These women were randomized on the day of their diagnosis and followed over a year. You almost never find something like that in American Yoga research. Most of these studies, because of expense, tend to be eight or twelve weeks. I think all of us know that Yoga is strong but slow medicine. When you measure something for eight or twelve weeks, you are not going to see much effect.

In fact, Garfinkel’s study was criticized in the letter section of the Journal of the American Medical Association: “Yes, they had a reduction in pain in some symptoms, but there have been no changes in the nerve conduction studies and therefore, we couldn’t really conclude anything.” For eight weeks of Yoga, to have a statistically significant reduction in pain, is pretty impressive. Eight weeks of Yoga is nothing! The benefits accrue over months and years, and if we are to believe those who have gone before us, decades. And, I believe them!

This study wasn’t just looking at their symptoms; it was measuring lymphocyte subgroups, helper cells, suppressor cells, natural killer cells, and cytokine levels using sophisticated Western technology. American studies tend to be small, maybe 8, maybe 20 patients. It’s harder to get a statistically significant result with so few patients. Whereas if you have a huge group of patients, even a small difference will be statistically significant.

Most Western research measures only the results of one main intervention. For example, there are two groups of patients. One gets a cholesterol drug and the other a placebo. Any difference between the groups then can be attributed to the cholesterol drug. The type of research that Dean Ornish did, on the other hand, is known as “outcomes studies.” His study was a comprehensive lifestyle study. The subjects were put on a program including a low-fat vegetarian diet, no smoking, group therapy, walking, and Yoga.

Of course, Western scientists tend to not really like those studies because they say, “Well, we can’t tell what did it. What had the effect?” What they fail to consider is that you get additive and multiplying effects, synergy, that happens with multiple interventions. This is one thing we should think about more in our research: not feeling like we have to say which element of what we are doing is having the effect.

After that, I attended a two-week Yoga therapy conference at the Krishnamacharya Yoga Mandiram (KYM) with T. K. Desikachar and his son, Kasthub. They have a different definition of research. They qualitative research. They study patients one at a time, come up with individualized programs for these patients and then try to see what’s working. They build a database.

From a Western standpoint that’s not considered acceptable. This kind of research has to do with a whole different way of knowing. In the Yogic way of knowing, the deeper you go in your own practice, the more you are able to see what other people need. This is where you see the real “art” of Yoga therapy. The KYM is a wonderful paradigm for Yoga therapy. They see people in one-on-one sessions. After asking questions and finding out the nature of the problem, they start to give them very gentle breathing practices and very gentle asanas. Depending on the person’s background, they may be given chanting and other things. The person does the practice with the teacher in the very first appointment—they might only do 2 or 3 asanas. Then they go home with homework.

At KYM, they focus on breath awareness in their asanas. You start the inhalation just before you initiate the movement and you continue the inhalation until just after you finished the movement. Then, you start the exhalation and you begin the movement back. Almost nobody gets hurt with this style because you are not holding anything. If you can’t do some part of the practice with smooth breathing, that is not going to be part of your homework. Similarly, they are not shy about including pranayama with retention to beginning students because they are always carefully monitoring them. There is continual adjustment over time. I think this is a powerful model for therapy—a model we should seriously look to in this country.

This is quite different from the Vivekananda center where they have set routines for heart disease, for diabetes, for back pain, and so on. To do research the way Western scientists like it, you need a standardized protocol. Vivekananda staff are willing to do that for the purposes of science. They do chanting, meditation, asanas, pranayama. But it is the same for everyone in the group. If somebody has a clear contraindication then they are not going to have that person do some parts of the routine. While I was at the Ashram, I saw some amazing results.

Next I went to Pune and took classes at the Iyengar Institute. I also watched the medical classes which they teach three times a week. Their paradigm is completely different. They are doing very prop-intensive things—bolsters, blocks, chairs and platforms. Iyengar invented most of the use of props, including for restorative purposes.

B. K. S. Iyengar is a master. He had a man with back pain doing the triangle pose. He had the man take his front foot and change the angle five or ten degrees in and out. Iyengar could look at the man and know what was happening with his sciatic nerve, how it was moving relative to other structures in his body, just with the changes in foot position. That is so beyond what any physician I’ve seen in the West can do.

In the medical classes, there are around 40 students and probably an equal number of teachers who come to study there. The teachers all act as therapists on the students, under the supervision of B. K. S. and Geeta Iyengar. I decided to watch Iyengar work for a month with a woman from Los Angeles. At age three, she had had open-heart surgery. She was left with wires in her breastbone and had real difficulty opening her chest. She had been a serious Yoga student for about 10 years, but had gotten frustrated by her lack of progress. She looked 10 years younger by the end of the month—her chest opened up, color came to her cheeks. She was transformed.

Ninety-five percent of the people who go to the KYM and Vivekananda Ashram are there for therapy. They have heart disease, diabetes, back pain or some other condition. I believe this is going to be the future of Yoga in the U.S.

One of the things that I went to India to try and reconcile was the Western, scientific way of knowing and the Yogic way of knowing. The challenge we are facing is that Western medicine is asking of Yoga: “What are the twelve poses for back pain?” What I would say to that approach is that patients are unique. Secondly, there are dozens of causes of back pain. In Western medicine, we don’t really learn how to distinguish them very well. There is pain caused by spasm; there are problems caused by ligament strains or by the sacroiliac joint. There are many causes of back pain. The idea that, even if patients weren’t all different—which they all are—one thing would help all those different kinds of back pain equally is silly.

How do we reconcile the Western paradigm and the Yogic paradigm? To me they are complementary, each providing a different view of reality, and there is much to gain from dialogue. My trip also made me realize that Yoga itself is not one paradigm. What they are doing at the Vivekananda Ashram does not look like what they are doing at KYM and neither of those looks like what they are doing at the Iyengar Institute. I think that the history of Yoga is the history of innovators all over the place—people who are creating new things and combining them. America is where most of that is happening right now. There are many teachers who have studied multiple styles, learned various types of bodywork, and are inventing their own things. I think that they are doing very interesting Yoga therapy.

The emerging Yoga therapy field is so varied in styles that it is hard to have quality control. The powers-that-be want some kind of standardization. It’s hard to fit the round peg of Yoga into the square hole of research and the needs of the managed care organizations. We have exciting challenges facing us and I’m sure the wisdom of Yoga will lead us.

Reprinted from Integral Yoga Magazine, Summer 2004