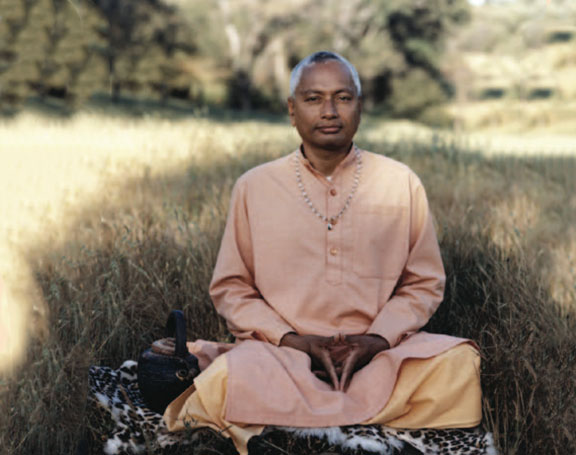

Both a renowned Sanskrit scholar and yogi, Swami Venkatesananda—like his master, Swami Sivananda—can be regarded as a sage of practical wisdom. Below is a transcript of one of his talks presented at Yasodhara Ashram (British Columbia) in the 1970s.

Both a renowned Sanskrit scholar and yogi, Swami Venkatesananda—like his master, Swami Sivananda—can be regarded as a sage of practical wisdom. Below is a transcript of one of his talks presented at Yasodhara Ashram (British Columbia) in the 1970s.

Perhaps you will be surprised to learn that not all the modern day asanas are mentioned in the Hatha Yoga Pradipika and the Gerandha Samhita. These two basic texts list some of the asanas you practice, but others are not mentioned at all. We know that originally, there were supposed to be eighty-four asanas, but somehow that list was greatly reduced. By the time these Yoga texts were written down, only four postures, all of which were meditation postures, were considered important.

Of these four only two remain popular today, the most famous of which is, of course, padmasana, or the lotus posture. The other, siddhasana may be less widely known by non-practitioners of Yoga, but it is considered by many to be the “supreme posture. ” Another name for it is “Adept’s pose.” Mentioned also are a few other asanas which you may know. For example, you find a forward bending pose, paschimottanasana, salabhasana (the ‘locust pose’), and bhujangasana (the ‘cobra pose’), both backward bending poses.

You’ll also find another popular and easy posture, dhanurasana (the ‘bow pose’). And, you’ll also come across some slightly more complicated poses, where you tie yourself in knots, such as kokkutasana and garbha-pindasana are also mentioned.

Although you find all these postures mentioned, very few postures were considered important. No doubt this was because these yogis intended to concentrate mainly upon pranayama and meditation. Postures other than padmasana and siddhasana were probably meant to enable the yogi to sit still for some considerable length of time, and to do so without discomfort. Also, they probably needed some postures to relieve the stiffness which could result from sitting for long periods of meditation. To facilitate meditation seems to have been their basic intention.

It was Swami Sivananda’s attitude that the Yoga asanas not only facilitate meditation but that the practice of Yoga asanas can itself be a dynamic meditation. From Swami Sivananda, we learned that the Yoga asanas are not merely a set of gymnastic exercises for the promotion of physical health, but can enable one to see the intelligence beyond the ‘me’ which exists in every cell of this body.

If you bring to this Hatha Yoga the proper spirit of meditation, you will discover the intelligence beyond the “me”, which is able to maintain the body, balance the body, and bring about the necessary adjustments from moment to moment in all these Yoga exercises. Then you will also discover that the same intelligence is fully capable of looking after the body, even bringing on pain and what you call “illness” if necessary. At that point, you don’t complain that you “don’t have time to meditate ” because you have discovered the key which transforms your whole life into a meditation.

Out of such a transformation comes a new angle of vision. No longer do you complain, grumble, or groan about a little pain illness, sickness, or even the shadow of death, because to you this ever changing life looks much like a lovely portrait in which there are dark shades and light shades, different shades of the same color. Your mind no longer rebels against illness, the shades of the painting, nor does it rebel against “old age” seeing clearly through the eyes of intelligence that time must keep moving on.

Seen through such eyes, there is no old age, but only time… progressing. Seen through such eyes, health and illness and even life and death are not different or antagonistic features. Through such eyes, life is continuous, all these being manifestations of the same intelligence. You must see it. You must see it in the face of someone like Swami Sivananda, whose body was riddled with all kinds of clinical diseases but whose face was radiant!

As I have said before, Swami Sivananda himself practiced and advocated only a few asanas for the daily routine. If you wish to do more, very good. One also learned from Sivananda that in the initial stages of Yoga what you call “physical health” is to be valued because initially illness acts as a barrier which prevents you from seeing this life stream within yourself. Unless you have already come face to face with this intelligence beyond the “me” you will not be able to look within, will not be able to transcend that ego barrier without physical health.

In the initial stages, the physically unhealthy body will constantly interfere with any attempts to practice pranayama or meditation, because the body will not stay quiet. Only the physically healthy body is capable of being quiet. In fact, in the physically healthy body, you are not even aware that you have a body!

For example, unless something goes wrong with your heart or your brain, you are not even aware that they are there. You are not aware of any internal organs unless something goes wrong. When something goes physically wrong, the intelligence in the body sounds an alarm, and sounds it loud and clear. That noise of that alarm will disrupt your ability to be attentive.

In performing Yoga asanas, the yogi observes that asanas have an influence on the blood circulation, direction of blood flow, on nerves, and glandular activity. The yogi is able to recognize the value of asanas, because he sees that as a contributing factor to physical health, the asanas can reduce the possibility that his body will become a hindrance in the practice of meditation. Also, the yogi recognizes that the physically healthy body clears a path for one to more fully experiment with the yoga asanas themselves, leaving him free to explore the natural rhythms and responses of a healthy body, and thus allow him to more fully appreciate the wonders of which this inner intelligence is capable. The Hatha Yogi’s aspiration is not to get involved with the physical but rather to extricate himself from it. Although the Hatha Yogi may not object to some amount of physicality in his practice, he wouldn’t want to get caught there.

I wonder if you can also see one very big disadvantage in regarding asana practice as therapeutic. When someone approaches Yoga because it is therapeutic, it means there is a motive or perhaps a hope in that person. In other words, there is already some expectation there in that person’s mind. This expectation is really another form of tension! And so if the person brings the expectation, he is already bringing a tension before he has even started. That person is working for health, and therefore, not relaxed.

Let me give you one classic example of how having an eye on some result can make you tense. Some years ago, a lady who had a rather incredible problem came to see me at a Yoga camp. She was suffering from something like insomnia, only it was more serious. She hadn’t been able to sleep very well in a very long time. She had gone to see all the psychiatrists in New York, in an effort to find someone who could solve her problem. Doctors had failed to help her. Having spent over fifteen thousand dollars on doctor bills in search of a cure, and having strained her purse to the limit, she had been referred to the Yoga camp by the last doctor she had been able to afford. She was a small woman, and she appeared to be shriveled up by her illness. She also had a wild look about her, perhaps from the drugs which had failed to help her. She came to my door, and not so much asked, as demanded: “I want your help! I haven’t slept in six months!”

I wanted to help her, but I had never run across such a problem. I asked her to come in and sit down. We talked, and later I gave her a mala (rosary) and a mantra, and told her to repeat the mantra until I returned in about an hour or two. I thought that the repetition might put her under. I came back to find her still awake: “I still cannot sleep!”

Not realizing that it would have any effect at all, I said to her: “What does it matter if you sleep? I have given you a very powerful mantra, the name of God! Why should you want to sleep now? Go on doing this mantra, and if you are able to avoid sleep you will go straight to heaven!”, and she slept! The moment it hit her that it wasn’t the only important thing she had to do, she slept!

If you start under the condition of hoping to get rid of something, you are starting with anxiety. Sometimes when you are asked a question about something you’ve studied, there is anxiety that you night produce the wrong answer. The answer should be available to you, but because of anxiety, there is progressively a greater and greater blockage of the answer. Consciousness has the answer which I don’t know for every situation. Right from childhood, you have messed yourself up. Somewhere along the line, you must end this vicious circle. You must become aware of this intelligence.

As you do that, you must learn to listen to it. Perhaps it is not the best expression, but “I must learn to obey it. ” You must learn to live in tune with it; not fighting, knowing that it is right. “Intuition” has become a rather loaded word, but depending upon your interpretation of intuition, it could mean the sane thing as “intelligence.” Reason cones in to play only afterwards, in order to justify what intuition has said earlier. (Of course, reason and logic have their place, in study and that sort of thing.) It is not possible that anxiety can occur because the body hasn’t taken proper care. Anxiety always cones first. Always! The intelligence will never make a mistake.

In doing even the simplest of Yoga asanas, there is much that can be observed. For example, uddiyana, the abdominal lift, is very easy. Every one of you here can do it. All that you have to do is lift up the abdominal muscles, and hold that position. Easy, simple to do! But have you ever asked yourself how you do it? Can you tell me right now what it is you do with each of those abdominal muscles? If you try, you will probably see that it is the abdominal muscles that know exactly what to do, while the mind can’t easily explain how it is accomplished. Try, if you like. Hold the posture right now. Hold it continuously. Holding it for some length of time, do you feel some tension there? Is this tension caused in the abdomen? Is it caused in the mind? Where does it come from?

What is tension? To find out, the brain need not get involved. In fact, the trick or secret to finding the answer is to leave the brain out of this entirely, and ask the question from within. If you can do that, you will see that the intellect is producing this “tension.” But if there is anxiety, your mind will be occupied with it, and you will not be able to watch. In fact you will have to get rid of your anxiety if you hope to watch what is happening in any of the asanas you practice.

Our anxieties over a particular Yoga asana seem to bear no relation at all to their difficulty. Sirshasana (the headstand), for example, has to be one of the easiest Yoga postures to do. You put your head down in front of the hands, with the hands forming a triangle, and you lift with the small of the back until you are in what can only be described as a half-headstand. From there, all you do is raise the legs up, and… …there you are, wondering: “How on earth did I get up here?”

Actually, it was all quite easy as long as there was no anxiety about getting it done. Before one has learned that the body can do this headstand quite easily, there is likely to be some anxious moments. If you are new to this posture you can be on the lookout for anxiety building up. Look to see if there is anxiety, because… as you shall see… the body is performing the posture, not your mind. It can do it without any help from the mind at all. When you experience the truth in this, you will probably be able to do the most complicated yoga asanas without anxiety. When you get past the anxiety, you will probably also see something which has never occurred to you before, namely that standing on your head should be easier than standing on your feet! I’m not joking.

When you stand on your own two feet, look down and examine the surface area that you are using to stand on. Approximate the amount of space that you are utilizing, or better still, ask someone to draw a circle around your feet while you stand there. That done, have that same person draw a tight circle around the entire area you utilize when in the headstand. The circle will encompass not only the head, but also the arms on both sides of the triangle. At once you can see that there is a much larger area to support your weight while in the headstand than there is while on your feet.

Of course I am not saying that by ridding yourself of anxiety you will be able to do every single asana perfectly. If your body is unable to do it, then.. the body will fall. But without anxiety, the body can fall out of that headstand and not be hurt. Just as a baby is able to tumble down a short flight of stairs and not get hurt, your body can tumble down out of that headstand without being hurt. Only anxiety will prevent the natural intelligence from following through with whatever is appropriate.

When you attempt a posture like trikonasana (the triangle pose) in which flexibility is tested, you can more readily see that the mind, in its anxiety, focuses itself upon the place where there is the greatest tension. The mind doesn’t want to continue holding the posture, because the tension is building. But that tension is simply the body telling you that you are not very limber. There will be tension at that precise point where the body attempts to make the needed adjustment. If you can hold the position long enough, the body will begin to readjust.

Perhaps this is the reason why the yogis recommended that when you practice asanas, you should stay in a particular posture until all the initial commotion is over. In doing that you have given the body time to readjust and regain normalcy. As a practitioner, our problem is that when the initial tension is received by the mind, in its anxiety, the mind focuses on that point where there is quite naturally the greatest tension, and gets worried: “Ouch! Stop that pain!” At such times, try shifting your attention away from the trouble spot to a place where there isn’t discomfort.

For example, when in trikonasana, the direction in which you bend will cause more stretching and discomfort in one leg while the other leg will be fairly busy trying to compensate for the unusual position of the body. The fact that there is no discomfort in one of your legs, plus the fact that it is doing quite a lot to keep the body balanced, makes it a good choice for a new focal point. when you shift the attention away from the leg that has discomfort, the pain will seem to disappear, and in turn, you will be able to hold the posture long enough for the body to make the necessary internal adjustments. Without the aid of a trick like this, you might give up, or else force yourself to hold the posture.

Forcing yourself to hold a Yoga position is to be avoided because the application of force does nothing to relieve anxiety on the contrary, forcing makes the asana feel more violent and frightening, and therefore, will only intensify the anxiety In an asana like sarvangasana (the shoulderstand—though why it is so called is rather puzzling because it’s not only the shoulders that one stands on but rather that the entire body is active, with the small of the back being the fulcrum), the body should “rest” without any commotion.

This is one reason why some teachers have suggested beginners support the pose with the use of their hands and arms. Later when you no longer need support, you may remove your hands. The important thing is that there should be no struggle. If you need a place to concentrate, try looking at the fulcrum of this asana the small of the back. When the attention is focused in such a way that there is no anxiety, you will see how beautifully the body adjusts itself from within, and will be able to discover the beauty which the body is!

The asana called matsyasana (the fish pose) is often performed immediately following the shoulderstand. Even beginners find this posture easy to maintain. However, there is usually exaggerated movement in the chest. All activity must have the gentleness which implies inward concentration inward feeling inward attention. In this way, you will easily realize that the lungs are fully capable of breathing without your assistance. Perhaps you will be able to meditate on the wonders of this physical body, realizing: “I would never be able to build a body like this!”

It should be possible for you to enter into a state of contemplation in any one of these Yoga asanas, whether it is the fish pose, the shoulderstand, the headstand, or any posture at all. And so, try to contemplate in every one of the Yoga postures that you practice. Meditate on the intelligence within, and all the incredible abilities of which this body is capable. Although the yogis mention only a few postures for meditation, realize that you need not be sitting bolt upright in padmasana or sirshasana in order to meditate. The body can be in motion, but the spirit can be in meditation. Why not?

About Sri Swami Venkatesanandaji:

Source: The YASODHARA YOGA TALKS – Swami Venkatesananda 1975

Copyright © 1997