In this article, Integral Yoga master teacher Rev. Jaganath Carrera discusses sutras 1.27 through 1.29 of the Yoga Sutras of Patanjali. In these sutras, Sri Patanjali introduces us to the OM mantra and the practice of mantra japa, which he explains is a most effective practice for removing the obstacles to spiritual progress.

In this article, Integral Yoga master teacher Rev. Jaganath Carrera discusses sutras 1.27 through 1.29 of the Yoga Sutras of Patanjali. In these sutras, Sri Patanjali introduces us to the OM mantra and the practice of mantra japa, which he explains is a most effective practice for removing the obstacles to spiritual progress.

Sutra 1.27. The expression of Ishvara is the mystic sound OM.

This sutra introduces us to the mantra OM, which denotes Ishvara. In the Sanskrit, the word “OM” isn’t mentioned. Instead, we find the term, pranava, the humming of prana. OM is the hum of the business of creation: the making, evolving and dissolving of beings and objects. You can hear it in the roar of a fire, the deep rumble of the ocean or the ground-shaking rush of a tornado’s winds. Since the pranava is not something we can easily chant, the name is given as OM. It is always vibrating within us, replaying the drama of creation, evolution and dissolution on many levels. This hum can be heard in deep meditation, when external sound is transcended and internal chatter stilled.

The identity of primordial sound with God as the creative force of the universe is not limited to Raja Yoga. It is a principle found in many spiritual traditions. The Bible declares, “In the beginning was the Word, and the Word was with God and the Word was God” (John 1.1). The Rig Veda, one of the most ancient scriptures in the world, contains a similar passage: “In the beginning was Brahman (God) and with Brahman was shabda (primordial sound) and shabda was truly the Supreme Brahman.”

Since the use of mantras is a central practice in many schools of Yoga, it will be useful to examine them in a little detail.

Mantras

Mantras (literally, to protect the mind) are sound syllables representing aspects of the Divine. They are not just fabricated words used as labels for objects. They are not part of the language as such. They are the subtle vibratory essence of things, presented as sounds that can be repeated. Concentrated repetition of a mantra forms the basis of an entire branch of Yoga: Japa Yoga, the Yoga of Repetition.

Sounds have the ability to soothe or agitate us. Many people shudder when they hear a metal utensil scrape the bottom of a metal pan. At the same time, countless vacationers seek out the shoreline in order to lie back and let the sound of the waves soothe their tattered nerves. Mantras are sounds that calm and strengthen the mind and, for this reason, they are ideally suited to serve as objects of meditation. The vibratory power of the mantra enhances the meditative experience.

Once a mantra has been chosen, practitioners generally make the best progress if they stick to it for life. Students may choose a mantra themselves, based on trial and error or because it is associated with a particular deity with whom they feel a strong connection. For example, OM Namah Sivaya is a mantra connected with Lord Siva. However, since the word Siva represents auspiciousness, the repetition of this mantra is not restricted to devotees of Lord Siva. Mantras transcend these designations. They are sound formulas whose fundamental benefit derives from their vibration, not associated ideas or images.

Some students receive a mantra from a master, or adept, in whom they have faith. In this case, they put their faith in the teacher to choose for them. The student is still making the essential choice in both scenarios. The difference is that, in the former, the student chooses the mantra; in the latter, the student chooses the teacher who selects the mantra.

Japa Yoga is not limited to Sanskrit and Raja Yoga. Repetition of powerful sounds and prayers—Shalom, Maranatha and Ave Maria, for example—is used in many spiritual traditions.

OM

The word used to denote Ishvara needs to be special: it should be free from the limitations of time, circumstance or faith tradition. Not only should this designation be universal, it must also bring the experience of Ishvara to the practitioner. Sri Patanjali states that the name that accomplishes this is OM.

OM is the origin of all sounds. It comprises three letters: A, U, and M (OM rhymes with “home” since the A and U, when combined, become a long O sound). A is the first sound. You simply open your mouth and make a sound. All audible sound begins with this action. It represents creation. The U is formed when the sound rolls forward toward the lips with the help of the tongue and cheeks. This represents evolution. Finally, to make the M sound the lips come together. This last sound represents dissolution. So together A, U, and M signify creation, evolution and dissolution. The entire cycle of life is represented in these three letters.

According to the philosophy of Advaita Vedanta (the philosophical school of nondualism), A is outer consciousness, U is inner consciousness, and M is superconsciousness. The same three letters also signify the waking, dreaming and deep dreamless sleep states. Beyond these three states is a fourth state, the Absolute, the silence that transcends all limitations.

Although there are many mantras, the source of all mantras is OM. Some of the more widely known mantras include OM Shanti, Hari OM, OM Namah Sivaya, and OM Mani Padme Hum. Most but not all mantras used for meditation contain OM.

Considering its symbolism and power, it is understandable why Sri Patanjali identifies OM as the “name” for Ishvara.

Universality of OM

Sri Swami Satchidananda’s commentary on this sutra says:

We should understand that OM was not invented by anybody. Some people didn’t come together, hold nominations, take a vote, and the majority decided, “All right, let God have the name OM.” No. God manifested as OM. Any seeker who really wants to see God face to face will ultimately see God as OM. That is why it transcends all geographical, political or theological limitations. It doesn’t belong to one country or one religion; it belongs to the entire universe.

It is a variation of this OM that we see as the “Amen” or “Ameen,” which the Christians, Muslims and Jews say. That doesn’t mean someone changed it. Truth is always the same. Wherever you sit for meditation, you will ultimately end in experiencing OM or the hum. But when you want to express what you experienced, you may use different words according to your capacity or the language you know.

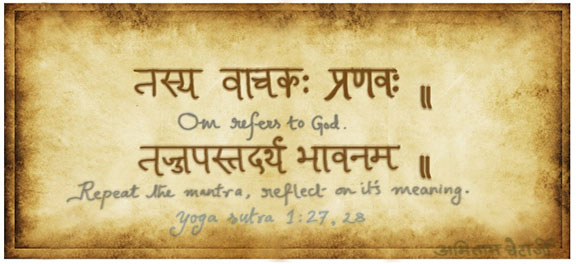

Sutra 1.28. To repeat it in a meditative way reveals its meaning.

The two key words in this sutra are artha and bhavanam.

- Artha signifies meaning, purpose or aim; from the root, “arth,” to point out.

- Bhavanam’s meanings include meditation, consideration, disposition, feeling and mental discipline. Some branches of Hindu philosophy understand bhavana as a particular disposition of mind—one in which things are constantly practiced or remembered.

Mantra repetition is not the mindless parroting of a sound but an attentive and informed act set against a background of enthusiasm. Steady mental focus and an understanding of the significance of the mantra are needed. In this way the meaning (or purpose) of the mantra will gradually unfold. This understanding is in harmony with one of Raja Yoga’s basic tenets: Focused attention results in deeper and subtler perceptions.

For keen seekers, each and every repetition is a moment of connection with the Self, an affirmation of the Truth of their own spiritual identity, and a reminder of their intentions.

Sutra 1.29. From this practice, the awareness turns inward, and the distracting obstacles vanish.

When the mind “tunes in” to the vibration of OM, it becomes introspective and begins to awaken to Self-knowledge. Meanwhile, the distracting obstacles (see sutra 1.30), which are the product of a scattered mind, naturally dissolve.

By extension, we could claim a similar benefit for the repetition of any mantra and for the practice of meditation in general (see sutra 2.11, “In the active state, they [obstacles] can be destroyed by meditation”).

This sutra introduces a key theme in Raja Yoga: The practices do not directly bring spiritual progress; they simply remove obstacles that prevent it. The evolution of the individual naturally occurs when that which retards its progress is removed. This principle is also found in sutras 2.2, 2.28, and 4.3:

- They [accepting pain as help for purification, study and surrender] help us minimize obstacles and attain samadhi.

- By the practice of the limbs of Yoga, the impurities dwindle away and there dawns the light of wisdom, leading to discriminative discernment.

- Incidental events do not directly cause natural evolution; they just remove the obstacles, as a farmer [removes obstacles in a water course running to his field].

About the Author:

Reverend Jaganath Carrera has shared the joy and wisdom of the Yoga Sutras with thousands of students worldwide. A longtime disciple of Sri Swami Satchidananda, he has taught all facets of Yoga at universities, prisons, Yoga centers and interfaith programs. He established the Integral Yoga Ministry, developed the Integral Yoga Meditation, and Raja Yoga teacher training programs. He is spiritual head of the Yoga Life Society. His book, Inside the Yoga Sutras is widely available.