If we look into creation narratives from different cultures, in almost every case the world is said to come into being through sound, through chant. Kirtan is the essence of Yoga, for by chanting the holy names, we experience a linking, a union, with the Divine. In this adapted excerpt from his book, The Yoga of Kirtan, Steven Rosen traces the origins of sacred chanting in the Vedic tradition and how it manifests in the different world faiths.

If we look into creation narratives from different cultures, in almost every case the world is said to come into being through sound, through chant. Kirtan is the essence of Yoga, for by chanting the holy names, we experience a linking, a union, with the Divine. In this adapted excerpt from his book, The Yoga of Kirtan, Steven Rosen traces the origins of sacred chanting in the Vedic tradition and how it manifests in the different world faiths.

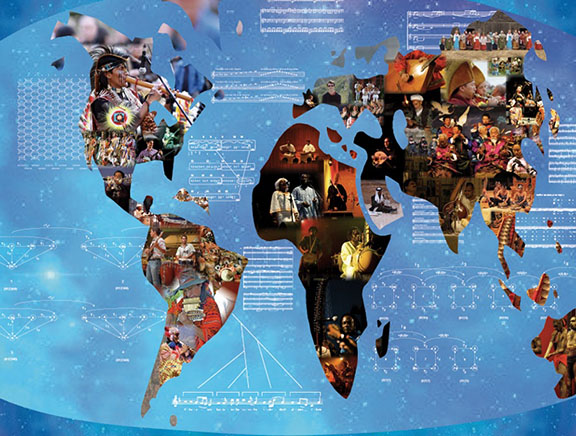

Sacred Chanting in the World’s Faiths

In Judaism, the hazzan, or cantor, is a type of kirtaniya, directing all liturgical prayer and chanting in synagogues around the world. If no cantor is available, a less qualified kirtaniya is called in, known as the ba’al tefilah. This person then chants the prayers, and the congregation repeats his every utterance, as in a traditional kirtan. The basic practice comes from a principle found in the Bible (Psalms 150.4-5), “Glory ye in His holy name. Praise Him with the timbrel and dance: praise Him with stringed instruments and organs. Praise Him upon the loud cymbals.” One of Judaism’s greatest mystics, the Baal Shem Tov, might be considered the ultimate kirtaniya—his very name means ìmaster of the good name,î and he encouraged his followers: “Chant, chant, chant!”

Jesus, coming from the same tradition, taught his disciples how to pray: “Our father who art in heaven, hallowed be Thy name.” This was the basis of early Christianity. In his Epistle to the Romans (10.13), St. Paul writes, “For whosoever shall call upon the name of the Lord will be saved.” Baptist choirs and church singers take this mandate to heart. Calling on the name became a formal part of the Roman Catholic Church during the days of Pope Gregory I (circa 540-604 C.E.). The Gregorian chant is only one of many chants in the Christian tradition. Christian mystics have given the world the Jesus Prayer, “Lord Jesus, Son of God, have mercy on me”—a continuous mantra-like incantation whose practice is similar to japa and includes repetitive rosary chanting.

The Muslim Qari are those who professionally recite the Koran. In tone and passion they easily bring to mind kirtan singers. Though demonstrative singing is not generally permitted in mainstream Islam, chanting to Allah is, and it is viewed as a particularly effective form of prayer. In fact, the Qari are kirtaniyas whose chanting is called tajwid, which is Arabic for “vocal music.” The ninety-nine names of Allah, called “The Beautiful Names,” are chanted on beads, inscribed on mosques and glorified in countless ways.

The Sufis, Islamic mystics, seek to evoke the divine presence by uttering God’s names. This is called “Qawwali,” a form of sacred Islamic vocal music originating in Pakistan and India—it is an art form or ecstatic ritual based on classical Sufi texts. One of its primary functions is to guide its listeners—those who delve deeply into its poetry and meaning—to a state of ecstatic trance (wajd), much like expert kirtaniyas of old. In Japan, followers of the Shinto religion engage in ritualistic chants, known as norito, which is their version of kirtan. Buddhist hymns are referred to as shomyo. This is a form of kirtan as well. In India, kirtan is a way of life. Sikhs, for example, view kirtan as central to their religious practice.

But where did kirtan begin? What were the earliest forms of spirituality to promote call-and-response chanting as a means to Self-realization? For this, we turn to the ancient wisdom texts of India.

The Vedic Roots of Kirtan

The Vedas and the Upanishads, which are among the world’s oldest religious texts, describe the power of sound in minute detail, elaborating on how certain mantras, when properly recited, reveal Ultimate Reality. Kirtan, then, claims both divine origin and a history traceable to the world’s earliest scriptures.

The scriptures state that for each world age, a specific method of God-realization is particularly appropriate: In Satya-yuga, millions of years ago, one attained the Absolute through deep meditation; in Treta-yuga, through opulent sacrifices; in Dvapara-yuga, through deity worship; and in Kali-yuga, the current age, through chanting the holy name of God. Even the celestial beings mentioned in the Vedic literature want to take part in this celebration of sacred sound. Lord Vishnu, for example, sounded his conch as a call to spiritual awakening, and Lord Krishna enchanted all living beings with his flute playing. Shiva played his tandava drum during the dance of cosmic dissolution. The Goddess Saraswati, depicted with stringed veena in hand, is the divine patron of music and learning. Lord Brahma, created musical scales with the mantras of the Sama Veda and used the specific mantra ìOMî to create the universe

This teaching—that material existence is generated through sound—resonates with the Bible: “In the beginning was the Word.” (John 1:1) Vedic texts state directly: “By divine utterance the universe came into being” (Brihadaranyaka Upanishad 1.2.4) These same texts tell us that just as sound had once instigated the original flow of cosmic creation, so, too, does it play a significant role in humankind’s ultimate goal: “Liberation through sound” (Vedanta-sutra 4.4.22).

In the sixth century CE, when bhakti (devotion) emerged as a vital force, yogis and singer-poets with mystic powers, conveyed truths, not only in Sanskrit—the language of the Vedas—but in vernacular using new compositions and contemporary songs. Most prolific were the Shaivite Nayanars and the Vaishnava Alvars, whose devotional poetry might be seen as first steps in the development of modern kirtan. With the help of scriptures, such as the Bhagavata Purana and the Bhagavad Gita, adherents came to understand chanting as a highly technical—if also blissful—discipline through which they could expect definite results on the spiritual path.

Bhakti literature and devotional song spread rapidly. As a result, four major lineages arose in South India, allowing primeval knowledge to flow north and, eventually, around the world. This was done through commentary and explication, practice and revelation. The four lineages owe a debt of gratitude to the following seers: Ramanuja (1017-1137), the initial systematizer for the Sri Sampradaya; Nimbarka (ca. 1130-1200), of the Kumara Sampradaya; Madhva (1238-1317), who appeared in the Brahma Sampradaya; and Vishnu Swami (dates unknown), who reinvigorated the Rudra Sampradaya, which was then reformulated by Vallabhacharya (1479-1545) as Pushti Marg.

Many branches, sub-branches and diverse traditions sprouted from these four traditions. The most significant in terms of kirtan would be that of Sri Chaitanya Mahaprabhu (1486-1533). His Gaudiya Sampradaya, an offshoot of the Brahma-Madhva line, inspired all of India with ecstatic song and dance, illuminating the science of kirtan as never before. As a teenager, Sri Chaitanya had become a scholar of significant renown, but by his early twenties he had set all academic pursuits aside in favor of love of Krishna. His transformation took place under the tutelage of Ishvara Puri, an accomplished teacher in the well-established Madhva lineage, who initiated him into the chanting of the holy name. Divine love emanated from his very being. The pandit (scholar) gave way to prema (lover of God). The path of knowledge, jnana (dialectics), moved aside, and bhakti reigned supreme.

Though Sri Chaitanya initially married and led a responsible family life, he eventually set aside worldly concerns, preferring instead the life of an ascetic, an itinerant monk. Unlike other mendicants of his time, who emphasized serious Vedic study and rigorous meditation techniques, he merely wandered from town to town, singing and dancing. He shared his considerable philosophy only when necessary, focusing instead on the love, joy and the understanding that comes from chanting.

With his vibrant yet simple teaching of divine love, he spent many years traveling India’s countryside, attracting numerous followers and disciples. The Six Goswamis of Vrindavan—who were arguably the most accomplished theologians of the time—became his disciples. They systematized his teaching and produced numerous volumes of profound philosophy. For the final twelve years of his life, Sri Chaitanya settled in Puri, deeply absorbed in meditation. His consciousness was immersed in the mystical dimensions of union and separation—the twin emotions of love. He shared these inner feelings with his most confidential devotees, not only with words but by the symptoms he exhibited in day-to-day life. He would cry and laugh simultaneously, like a madman; run after shadows, hoping they were in fact his beloved; and passionately call out, “Krishna! Krishna!,” like a victim of unrequited love.

His followers observed him carefully, taking scrupulous notes. Documenting his every move, they devised a science of devotion, noting exactly how love of God develops, the symptoms one experiences along the way and how to gauge proper advancement on the path. Although widely known as a scholar in his youth, Sri Chaitanya left the world only eight verses, called “Shikshashtaka,” which sum up his teaching. At first glance, the verses seem rather simple, but they are not. They express an appreciation for the holy name; an awareness of exactly how the name should be chanted; an element of regret, showing how one should hanker for greater taste in the practice of chanting; the importance of humility in approaching the name; and finally the overwhelming feeling of love in separation, where one is virtually consumed by the desire to unite with God.

Additionally, sophisticated love poetry, systematic theology and new revelations came from many quarters. Chief among these, perhaps, was the Gita-Govinda, Jayadeva’s twelfth-century Sanskrit work on the love of Radha and Krishna. The great kirtaniyas who developed Jayadeva’s theme include: Sur Das, Tulasi Das, Tukaram, Namdev, Mirabai, Vidyapati, Chandidas, Swami Haridas, Narottam and Bhaktivinode Thakur. And there were countless others who wrote devotional songs on the same subject, elaborating on divine love, as found in the spiritual world. The practice of kirtan is forever indebted to them.

About Steven J. Rosen

About Steven J. Rosen

Steven J. Rosen is editor-in-chief of the Journal of Vaishnava Studies, a biannual publication exploring Eastern thought. He is also the author of over twenty books on Indian philosophy. His recent titles include Essential Hinduism (Praeger, 2006), Krishna’s Song: A New Look at the Bhagavad Gita (Praeger, 2007), and Black Lotus: The Spiritual Journey of an Urban Mystic (Harinam Press, 2007). He is an initiated disciple of His Divine Grace A.C. Bhaktivedanta Swami Prabhupada. For more information, please visit his website: yogaofkirtan.com.