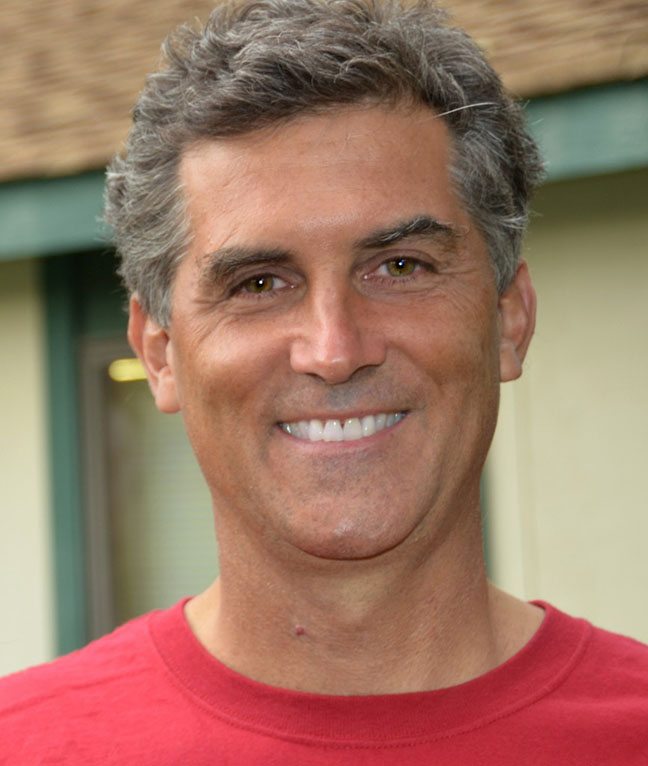

Robert Butera, Ph.D. studied at the Yoga Institute in Mumbai, India, where Yoga is viewed as a spiritual practice and a total lifestyle. A contributor to Integral Yoga Magazine and presenter at Satchidananda Ashram–Yogaville, Dr. Butera explains how asana is part of the eight-fold Raja Yoga path and thus a step in a much broader journey. In this interview, he summarizes his ten-step approach to asana as a tool of transformation.

Robert Butera, Ph.D. studied at the Yoga Institute in Mumbai, India, where Yoga is viewed as a spiritual practice and a total lifestyle. A contributor to Integral Yoga Magazine and presenter at Satchidananda Ashram–Yogaville, Dr. Butera explains how asana is part of the eight-fold Raja Yoga path and thus a step in a much broader journey. In this interview, he summarizes his ten-step approach to asana as a tool of transformation.

Integral Yoga Magazine (IYM): How do you view asana?

Robert Butera (RB): My outlook on asanas is 100 percent guided by sutra 2.47 in Patanjali’s Yoga Sutras, which tells us that Yoga poses are perfected when one completely relaxes and meditates on the infinite. There’s an irony in that. When you do a Yoga pose from a more spiritual perspective, you obtain more physical benefits. When you do an asana and you’re physically in the pose—in alignment and breathing—if your nervous system is agitated in any way, you will decrease the benefit you receive in that pose. If you learn how to connect to the infinite or have a broader perspective in the pose—where your ego is no longer the sole focus—then your nervous system steadies and you reach closer to a meditative state while having a physical experience. If you look at Olympic athletes who have mastered the 100-yard dash, they run as if there were no effort involved. For them to reach maximum speed, their nervous systems must be completely focused. The same is true for us as we try to get the full benefit from a Yoga posture.

IYM: How can one use asana for personal transformation?

RB: Let’s first define transformation in Yoga’s terms—not necessarily western psychology’s terms. Yoga traditionally was transmitted from the guru to the disciple, one-on-one. Group classes are more a modern trend as, classically, the majority of the learning happened one-on-one. So, transformation was based on the individual’s needs. If we apply that to individuals in modern society we would want to first focus on whatever areas in their lives are the most in need of balancing or improving. So, the transformational process in Yoga would first address that need, rather than having a set program that each student follows in the same manner. For some, the transformation will occur when they become aware of their bodies. They may be more developed psychologically or spiritually while out of touch with their physical bodies. Likewise, the breath could be a huge opener for certain individuals who have any type of blockage in their energy or prana. Another person may feel spiritually stuck in life and may find that deeper study of Yoga poses allows them to feel inspired.

IYM: How can we deepen our practice of asana?

RB: The first step is to understand where you are right now in your practice. For example, in the workshops I teach, I find that I can’t introduce any new ideas until the students first recognize their own bias in Yoga poses. What I mean by bias is the way in which they are doing the poses or focusing on the poses. The most common bias is to be obsessed with physical alignment and to not think of anything but where to place your body—the underlying belief is that a perfect body position leads to enlightenment.

Another example of bias relates to a person who begins to get in touch with his or her emotional body and tends to feel the majority of the poses through the heart. That person then starts to alter the alignment so the heart opens in poses where it isn’t supposed to. We superimpose our bias on what we think the Yoga pose should be, as opposed to going into the asana with an open mind and trying to figure out what the asana, in its purity, wants to be. If you can understand your bias, you can decide if working on your heart, breathing, relaxation or alignment is the appropriate thing that opens you up to higher consciousness. Over time, this will continue to evolve as things change in your life. That process seems to deepen people’s asana practice, because we often get into patterns or ruts with our practice over time.

IYM: Would you give an overview of the ten-step process you delineate in your book, The Pure Heart of Yoga?

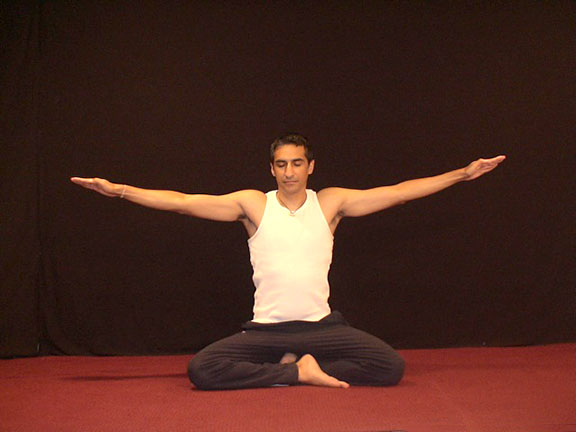

RB: Yes, I give ten basic steps on which to focus in order to explore deeper states of consciousness while doing the asanas. Step one is intention (sankalpa). When you set an intention, it immediately connects your mind and body to the practice in one seamless unit. Personalizing your intention empowers your practice and your life. Step two is attitude (bhava). By cultivating an awareness of your attitude, you connect with the nonphysical essence of asana practice; you learn to create a harmony of mind, body and spirit through your attitude. Step three is posture, (asana) which addresses the physical alignment of the asana and the understanding that the body is an essential part of spiritual experience.

Step four is breathing (pranayama), which focuses on the breath as a bridge to divine consciousness. Step five is archetypes (purvaja). This step connects the asanas to nature and understanding the story behind each asana. Step six is energy centers (chakras). Having an understanding of our energetic anatomy can help us move beyond the physical asana so we connect to a higher reality. Step seven is concentration or (dharana), in which we minimize distractions to enhance concentration to go beyond ego into a pure experience in asana. Step eight includes the locks (bandhas) and seals (mudras) that help us to connect to subtle energy and manage the energetic body. Step nine addresses the psychological blocks (kleshas) that are the obstacles or hindrances to one’s practice. Step ten is emotional transformation (bhavana) which is a process of awareness, acceptance and transformation of negative or limiting emotions.

IYM: How does one work with the steps?

RB: I recommend working through them, one by one. It is not a timed, set program; the steps provide a template that grows with you over time. Certain steps become more relevant than others at different times in your life. Each step, if it’s appropriate for the student, has the effect of connecting them to the infinite. You can focus on alignment, if that’s the appropriate thing for you, and have a profound experience, but that usually lasts only for the first phase of a person’s Yoga journey.

I’ll give a few examples of how we work with the steps. Let’s consider step two, bhavana, the attitude of each posture. The root of the word posture is attitude. A haughty posture expresses an attitude of aloofness. A forward bend expresses an attitude such as surrender or letting go. When you explore the nuances of the poses, if you are able to understand what attitude is gifted to you while performing the asanas, you may discover new insights.

To work with step five, purvaja, we focus on the archetype of the pose. Yogis studied nature in order to discover the archetype or wisdom of each aspect of nature such as animals’ structures. That’s why asanas have names such as cobra, peacock, fish pose and so on. Human beings have the ability to mimic or in yogic terms, “become one with” these various qualities found throughout nature: the mountain, the tree pose, sun salutation—therefore you can have a similar experience described by the attitudes. For example, the attitude of the lion pose is courage. When you use the archetypal aspect, you are focusing in a more prayerful, visual way. You use a visualization, so it’s a more visceral feeling, where the attitudes are more intellectual. It’s interesting to study the archetypes and how this plays out in our personalities and lives.

IYM: Step ten is emotional transformation. Is there a psychological dimension to asana?

RB: Inherent in all Yoga practices, and yes I mean all, there is an implicit psychological dimension. Often, westerners compartmentalize life and they only see the physical aspect of Yoga poses, the psychological aspect of relationships and the spiritual dimension in terms of meditation. In Yoga, there is the mind-body-spirit connection in every aspect of the practice. One way of working psychologically when doing asanas is to explore areas of physical tension. For example, Mr. Smith does asanas to alleviate his neck tension from his long daily commute to work. However, as he studies Yoga further, he realizes that the way he holds the steering wheel is the same way he sits in meetings. He’s very opinionated and he’s learned to keep his mouth shut in meetings, but bottles up tension in his neck. His discovery must go into why he has this challenge in the first place. As he gains insights and opens his mind over time, through his Yoga practice and mindful approach to living, he’s able to release the neck tension. So, the process of transformation requires effort on all levels of oneself.

IYM: How do you see asana practice evolving in our culture?

RB: There’s a lot of confusion in the West about what constitutes Yoga practice. This is unavoidable when someone learns Yoga in a fitness club environment where there isn’t a strong sense present of the Yoga tradition. Then, once students go deeper into the tradition, they may find comfort in a specific Yoga style and then a much stronger block surfaces: when someone becomes a little too attached to their approach. It really doesn’t matter what style of Yoga we practice. We just need to figure out what suits our physical constitution and preferences. Ultimately, the right way to do Yoga is to use the practice to expand and heal ourselves so we may connect with the infinite.

About Robert Butera: