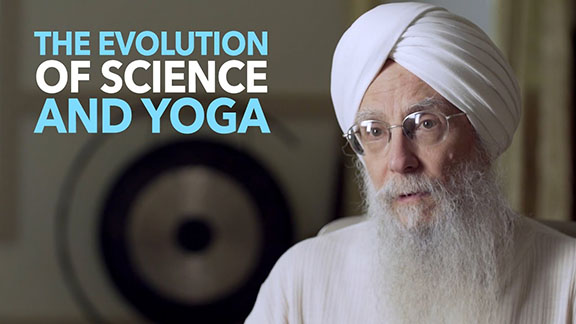

Sat Bir Khalsa, PhD, is one of the leaders in Yoga therapy research. He was drawn to approaching Yoga as a physiological practice because he believed that providing the science behind the practice would help Yoga to penetrate the mainstream. In this interview he talks about his work, future directions of Yoga therapy and the necessity for Yoga therapists to embrace research.

Sat Bir Khalsa, PhD, is one of the leaders in Yoga therapy research. He was drawn to approaching Yoga as a physiological practice because he believed that providing the science behind the practice would help Yoga to penetrate the mainstream. In this interview he talks about his work, future directions of Yoga therapy and the necessity for Yoga therapists to embrace research.

Integral Yoga Magazine (IYM): How did you get involved in Yoga research?

Sat Bir Khalsa (SBK): In the mid-1970s I set myself a goal to do Yoga research. As a first step towards this goal, I proceeded to get research training and a PhD in the field of neurophysiology and neuroscience. Despite being interested and open to doing this research I wasn’t able to begin doing Yoga research until the year 2000. As a full-time researcher, you are fully engaged in the project you are funded to carry out and it is difficult to do other research on the side. It wasn’t until 2000 that the National Center for Alternative and Complementary Medicine started funding major research grants that I was able to acquire the necessary funding to put me in a position to do Yoga research.

IYM: With what type of Yoga research did you start?

SBK: The project that fit my expertise was an evaluation of a Yoga intervention for insomnia. I was in a good position to apply for a research career award with my long history of Yoga practice and my research training in circadian rhythms and sleep. There is a lot of evidence that people with chronic insomnia have elevated levels of arousal. This arousal manifests in an increase in the stress hormones cortisol, adrenaline and noradrenaline. Other arousal measures have also been shown to be elevated—like body temperature and metabolic rate. It therefore makes sense to use Yoga in the treatment of chronic insomnia because Yoga has been shown to be very good at reducing arousal.

IYM: Is there a difference between doing Yoga research and being a Yoga therapist?

SBK: They are two very different approaches. In the case of insomnia, a Yoga therapist needs to apply the most appropriate treatment for different individuals with chronic insomnia. The ideal approach for people with chronic insomnia is to give them all the behavioral treatments that are already known to be effective and to add Yoga to that.

In contrast, in Yoga research for insomnia everything is ideally simplified, regimented and reproducible. I picked a practice from Kundalini Yoga, as taught by Yogi Bhajan. It is a 45-minute set of exercises: three postures, a breathing pattern that includes breath retention and meditation. The subjects receive the treatment in a training session and they practice this routine every night for eight weeks. We monitor their sleep and do overnight sleep studies to examine any improvements in sleep. The preliminary study showed statistically significant improvements over time. Since then we’ve run a randomized control trial in two groups and have shown similar improvements over time in the Yoga group again.

IYM: You teach a mind-body medicine class for Harvard medical students. Can you talk about what students learn in this class and what impact you see this having on Yoga therapies’ acceptance?

SBK: The course is on the general field of mind-body medicine. We’ve opened the course up to students from other Boston medical schools, the Harvard School of Public Health, Harvard Divinity School and others. There are 16 seminars given by research faculty who are leaders in their fields within mind-body medicine. We include lectures on the history of mind-body medicine, spirituality, placebo effect, biofeedback, meditation, Tai Chi, Yoga and the practical aspects of delivering mind-body interventions in clinical settings.

Students have an option to take a one-hour Kundalini Yoga class that I teach after the seminar; I would say half of the students stay for the Yoga class. A lot of these students go through a transformation through the regimen of a consistent Yoga practice. The direct mind-body experience they get from Yoga changes their approach to life and potentially their future roles as healers. Although, it is gratifying to enlighten medical students directly through Yoga practice, I think research on Yoga can make a bigger impact because published research has the potential to change what is taught in medical schools.

IYM: Why do you think Yoga research is necessary?

SBK: Yoga is extremely popular; it has become a cultural icon. Yoga is becoming something that is part of being a westerner. Surveys show that 5 percent of the population is practicing Yoga and that many of these people are practicing for health reasons. However, if you look at the demographics of these surveys, the practice of Yoga is done primarily by people who are of higher education and income levels, female gender and those who are younger. This means that only a very narrow sliver of the population is practicing Yoga. Those of us who believe that there are enormous health care and wellness benefits to the practice of Yoga would like to see Yoga being practiced by the entire population.

If you really believe in the benefits of Yoga, the question is how can you get Yoga to be practiced by the full population? The answer is to link Yoga to a mechanism, or system, that already penetrates the entire demographic. The two systems in society that already do this are the education system and the health care system. This is where the research component comes in; the education and health care systems will not incorporate anything unless it has been validated scientifically. Research is necessary to convince the administrators in both of those systems that Yoga belongs.

We need to show that Yoga is a valuable adjunct to treating a variety of disorders: depression, anxiety, obesity, diabetes and insomnia—the list goes on. I believe that Yoga practices should be incorporated as an adjunct treatment, as a mind-body therapy in coordination with allopathic medicine. The same applies to the education system; we need to show that giving Yoga practices to kids in schools improves grades, performance, psychological state and concentration, while it decreases aggressiveness, anger, depression and anxiety. If we can show this repeatedly in a number of well-controlled experiments then educators will incorporate it.

A good analogy useful for understanding the role of research is the concept of cultural hygiene. One such hygiene practice that is well established in our society is dental hygiene. It is well recognized by the medical system and it is well incorporated into the education system. If you are brought up in this culture you get exposed to it, period. If you travel, you take a tooth brush. It is part of life, of who we are as a culture. Now, when you compare this with the prevalence of what I will call “mind-body hygiene,” or the ability to maintain wellness of our mental and physical state, we are very poor at this.

We have very little in place that teaches our children how to cope with emotions, life events and stress. The education system has virtually nothing established in its curricula that focuses on stress management, physical and mental flexibility, disease resistance, anxiety, depression, trauma and stress in general. As a consequence, an enormous part of our health care system is devoted to illnesses that are the consequences of chronic unmanaged stress. We spend a lot of money treating illnesses in the adult population that are effectively behaviorally induced lifestyle diseases.

Evidence suggests that the practice of Yoga will improve emotional tolerance and stress management; it can reduce aggression, greed and suffering. We are talking about reducing our health care costs. More importantly, we are talking about improving our human experience as individuals and as a society.

IYM: Do you see any resistance to incorporating Yoga into the schools due to issues of separation of church and state?

SBK: At its core, Yoga is a physiological practice. Meditation is a very simple cognitive process. The regulation of the breath and the stretching of the body are physical activities that generate physiological responses. It is so simple. Although Yoga comes from a culture that has mantras, fancy names for asanas and is deeply spiritual, the truth is, you can teach Yoga without all of that and it is just about as effective. This is what we need to focus on for Yoga to reach the most people.

The grassroots movement of implementing Yoga in education is alive and well; many schools have after-school programs of Yoga. However, this is happening primarily in affluent school systems and in few regions of the country. It is likely you will find little Yoga practiced in schools in North Dakota farming country or in disadvantaged neighborhoods in urban southern cities.

IYM: What do you think makes an effective Yoga therapist?

SBK: I believe Yoga therapists are more effective if they document more of what they do. What I mean by documentation is carefully conducted and written case studies, reports, questionnaires and interviews. It is essential that Yoga therapists report what they have done. Let me give you an example: In the 1970s, our 3HO Foundation that disseminates Kundalini Yoga as taught by Yogi Bhajan ran a state-funded drug rehabilitation program in our ashram in Tucson, Arizona. Participants lived in the ashram, did morning sadhana, Yoga, yogic diet, juice fasts and detoxification routines. Many people were really changed and transformed. However, because we did not fully document the progress and outcomes of this program on the participants, there remains little to show for the success of the program save for a number of personal anecdotes, and these anecdotes will themselves be lost in time.

IYM: Some Yoga therapists see their work as treating the whole person rather than specific diseases or disorders. Can you talk about the ongoing critique of Yoga as a therapy?

SBK: You can go back into the literature in India and see critiques about using Yoga for therapy alone. The argument is that Yoga is not just a medical intervention but rather a traditional, ancient, spiritual practice that brings the whole individual into balance. It is understood the practice of Yoga is about treating the entire individual to raise their consciousness, to become a better being. Therefore, the view has been expressed that practicing Yoga as a therapy alone for a specific disorder is demeaning to the full intent of Yoga.

When anything becomes popular it becomes diversified—that is well understood. When the car was first invented and you wanted to buy a car there was one model to buy. Now you have a choice: motorcycle, truck, sports car—what brand do you want? What color? The diversification is endless. The same is happening with Yoga. As Yoga becomes more popular it is going to diversify. We now have comprehensive Yoga styles like Integral Yoga, Kripalu Yoga and Kundalini Yoga, which are focused on the growth of the whole individual and include postures, breathing, meditation, philosophy and psychology of Yoga. We now also have what can be considered more limited styles of Yoga; in the most extreme case, Yoga whose focus is entirely on the physical practice for cosmetic purposes. It is easy for us to look at this type of Yoga practice derisively and say, “Oh what a joke! Yoga is so much more than that! Look what these guys are doing to it!” However, even in this limited application of Yoga, people are practicing an exercise that has the potential to be a little more effective at stress management and improving well-being than the other exercise options at the gym. Perhaps some of the students who started out doing “Yoga for the abs” are going to eventually gravitate to a more comprehensive practice, yet those students may never have been attracted to a more comprehensive style of Yoga first.

IYM: Do you have any advice for those interested in researching Yoga?

SBK: For Yoga instructors and therapists interested in research, I would say that Yoga research begins at home. It all starts with documentation. One of the good habits of any clinician is documentation. A lot of therapists pride themselves on being completely intuitive; that they feel their way through sessions with people. These practitioners may feel there is no need for an analytical component to their work. However, by documenting your work you get to look back on your progress; you get to see what worked and what didn’t; you get to observe how things have changed over time. Yoga therapists need to become very good at clinical documentation.

Once you have clinical documentation you can write case reports or case series reports or your documentation can be reevaluated for quality control. For example, if you are using Yoga to treat headaches, you can look at your documentation and see, “Oh, only people doing the breathing practices are getting cured of their headaches.” You’ve learned something! Then you can increase your use of breathing practices and see if you get better results; you may prove to yourself that pranayama is the best technique for headaches. This is the power of documentation; a lot of these findings don’t come out until you fully analyze the data. If it is something subtle, the only way you are going to find it is by documenting your work. Documentation is good clinical practice no matter what you do or what system you work in. You have to treat the patient, but also make time to document your treatment and the response of the patient.

About Sat Bir Khalsa, PhD

Reprinted from Integral Yoga Magazine, Fall 2008