Photo by Subhradip Pramanik on Pexels

My father would have been in a coffin when I was 16 years-old had he not noticed subtle changes in his breathing and the way that he felt while running on a treadmill at the gym. My father was an avid runner, and a wonderful example of one who takes care of their health. In the 1980s, for him, that meant exercising regularly by jogging. It’s thanks to his good example that both my parents were successful in pushing my sister and I to swim competitively from grade school through college.

The signs of my father’s ailing health included chest pains. He said it felt as if a heavy weight was tied to his chest, and his left arm squeezed by a blood pressure cuff. Shortly after his complaint he went to a heart doctor who diagnosed the disease of atherosclerosis or hardening of the arteries. Atherosclerosis is the result of plaque building up in the system that then attaches to the arteries restricting the flow of blood through the body. If left untreated, it could lead to a heart attack or stroke depending on where the arteries are affected.

When I was 14, my maternal grandfather died at the age of 72 from a stroke, most likely because of the hardening of his arteries. My maternal grandmother, while living into her 90s, had heart surgery to prevent the same disease my father had. My paternal grandfather died in his early 50s. He also died of a stroke due, in part, to atherosclerosis. I never met him.

My father was only 52 years-old when he had bypass surgery, and we could very likely have been attending his funeral had he done nothing. It was a traumatic experience for the whole family. I remember immediately after the completion of surgery, per doctor’s orders, that our family was asked to keep my father awake and upright despite his constant falling asleep. “Dad, wake up!” I think they wanted to keep his heart rate from dropping too drastically, to make sure that everything was working properly. The family took turns watching him for a couple of hours until he was allowed to rest fully.

Because of the family history, my doctor recently suggested I get a stress test despite having normal levels of cholesterol. My feet would be pounding on a treadmill, with wires attached to my chest, giving the doctor the picture of what’s happening to my heart while under pressure.

My father researched condition like Siddhartha seeking enlightenment under the Bodhi tree. He wanted to understand how atherosclerosis happens and what he could do about it—something that all of us in the family learned from: the path leading to the end of suffering via diet, exercise, and stress-management

In his research about the causes of heart disease, my father also found out about, “the cows revenge.” He learned that eating red meat and dairy largely contributed to heart disease. This was a huge insight for the whole family, for red meat and dairy were consumed daily without second thought. For a while my mother stopped cooking red meat because of my father’s insistence.

This practice stayed with me when I went off to college the following year. It wasn’t so much a conscious decision as much as a no-brainer to learn from my father’s lessons, even though everyone around me—my classmates and fellow members of the swim team—was eating meat. I didn’t completely give up red meat at that time, but I certainly modified my intake and began to choose chicken over beef. I was at a young enough age that my mind was flexible to change deeply ingrained dietary patterns given the right encouragement. It took four more years and the watching of a film on the meat and dairy industry, as well as taking a college class on Buddhism, that had me thinking about becoming a vegetarian—and I do mean thinking about it, not practicing it.

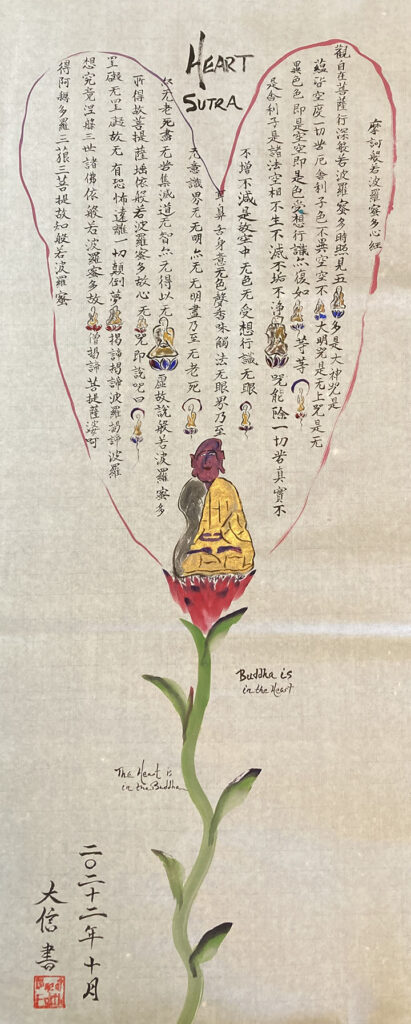

Artwork by Daishin McCabe

I confided in Dr. Mary Evelyn Tucker—one of my professors who was a practicing vegetarian—that I was thinking of becoming a vegetarian. She said to me, “You might want to learn more about how to do that before jumping in.” In hindsight, this was sage advice. Too many people jump into being vegetarian and don’t have the slightest idea of how to eat or how to cook for themselves. They often end up eating carb-heavy meals leaving out adequate vegetables and protein sources, and also don’t understand the need for B vitamins.

When I was in college I had no clue how to cook for myself, so for the next several years I resigned myself to eating what was served by my mother (which was by then often red meat and dairy), and by the larger society. When I went to Mount Equity Zendo, at the age of 23, I thought, “Here’s my chance to become vegetarian.” I learned how to cook brown rice, miso soup, and veggies. I learned multiple ways of creating delicious tofu dishes. Gradually, I learned about the importance of protein that comes from eating beans, quinoa, nut butters, and soy products. It took me years to learn how to balance my diet so that I wasn’t just eating carbs like bread and pasta.

While the environment was much more vegetarian-friendly, still, as a priest, I was expected to eat whatever was served. There’s a Zen saying, “A monk’s mouth is like an oven.” In other words, don’t make preferences. If someone brings meat, eat it—don’t call up the mind that picks and chooses. This is how they did things during the Buddha’s time and eating meat was okay if the food was not killed specifically for you, and you did not hear the screams of the animal being slaughtered.

To illustrate the point of the Buddha’s injunction to not eat meat if it was specifically killed for you, I share the following: One time a monk, who had been practicing in the Burmese tradition, came to our Zendo in Pennsylvania to offer a Dharma talk. He disclosed that when he went to stay with his sister, she served him shrimp. Just before he was about to eat it, his sister remarked, “I hope you like it, I bought it just for you.” He stopped and pushed the plate away telling his sister that he wasn’t able to eat the food precisely because she bought it for him. The practice of not eating meat (including fish) within early Buddhism may have been originally about not causing harm to animals unnecessarily. The animal could not be killed for a monk. Killing an animal would incur negative karma for the monk. He would be breaking the first precept, “Do not kill.”

However, if the animal had already been slaughtered, and not for a particular person, then it was acceptable because, in part, it had already been killed. In that case, the monk did not cause the animal to be killed, and therefore was free of the consequences of the karma generated by killing the animal.

Today, in Japan, most monks (and the Japanese as a whole) eat meat, though they eat a rather small portion compared to the average American. They only follow the rules of not eating meat (in most cases) when they are eating formally. But the rule of not eating meat is largely ignored. Nevertheless, when training in a Japanese Zen monastery, the diet consisted largely of brown or white rice, miso soup, vegetables, sometimes eggs, and tofu. This diet, while an excellent break from the diet of veal parmesan, fettuccini alfredo, and other meals my mother would make for me, wasn’t going to be sustainable for me for the long-term.

After a three-month stint in a Japanese monastery, a test revealed serious deficiencies in my blood. I decided to visit with a Naturopathic doctor. While not going into detail, this doctor helped me to take a much larger perspective on the issues I was having, encouraging among other things, further dietary changes that included eating whole foods and consuming different forms of protein (not animal-sourced), and getting a minimum of nine hours of sleep per day.

He also had me reconsider my meditation practice. Thus far, I had largely neglected using meditation as a means for dealing with stress or to relax. It was more about being attentive, but I wasn’t balancing that attentiveness with rest. My health, thankfully, has improved so much that my allopathic doctor is no longer concerned about my bloodwork. To this day I still find myself learning from the things my naturopath taught, and doing my best to practice good health on the physical, mental, and spiritual planes.

As my health was steadily improving, I asked my teacher for permission to go to Yogaville to go through Yoga Teacher Training. I was moved by the devotion to a plant-based lifestyle that I witnessed at Yogaville. Could I do that? For a variety of reasons I found it impossible to practice and take full responsibility for not eating a vegan diet until years later. When I reflect back, I am deeply grateful for the example set at the Ashram. Yogis like Meenakshi Angel Honig and others from Integral Yoga continue to inspire my eating habits.

More recently, my father has had further complications with his heart. As I was talking with my mother about my father’s worsening condition all stemming from his heart, she asked me if I had gotten my cholesterol checked recently. I said that I had, and that my levels were totally normal, and that I’m also not worried about heart issues because of the well-documented connection between heart disease and diet. My mother is still of the mindset, along with much of the medical community, that heart disease is purely genetic.

Photo: Daishin’s mother and father, Prudy and Mike McCabe.

When I reminded my mother about “the cow’s revenge” she laughed at me pointing out that my maternal grandfather ate very well his whole life. No doubt he ate well. He exercised well, too. Still, in a traditional Italian American household there’s no escaping a diet high in animal fats, dairy, and red meat.

I reflect on this now because I feel more and more confident in my choice to move toward a vegan diet. I’ve felt healthier than I ever have in my life, and I am happy that, every time I eat a meal, I am not breaking the very first of the Buddhist precepts: do not take life. Further, the third “Less Grace Precept” of the Brahma Net Sutra, an important writing connected to the 16 Bodhisattva Precepts, explicitly states:

Disciples of the Buddha, should you willingly and knowingly eat flesh, you defile yourself by acting contrary to this less grave Precept…. Anyone who eats flesh is cutting himself off from the great seed of his own merciful and compassionate nature, for which all sentient beings will reject him and flee from him when they see him acting so.

I know that I am benefiting living beings by choosing to be vegan. The first of the four Great Bodhisattva Vows is, “Beings are numberless, I vow to free them.” What better way to do that then to not eat animals? People often wonder, when they hear about the sorry state of our planet, whether it be the climate crisis or mass migration, what they can do to help. Should they go to Japan to practice? Should they go to a third world country to help out those who are in a dire situation? These are all noble questions, but what often escapes us is how our food choices, something we can change in any moment, can potentially free all beings. Do our actions need to be dramatic to save all beings? Can we not see the courage in the act not to eat meat?

What escapes us is the fact that in every meal we make choices that can better the planet. We don’t need to go anywhere. We need to look at how we use the almighty dollar in the grocery store. Diet is perhaps one of the easiest places to turn to when we think of improving the state of the world. The food choices we make have ripple effects on the well-being of the earth. Many of the fish in the oceans are disappearing. We do great harm to factory farm animals like chickens and cows that are penned up for their whole lives. We ingest not just their meat, but their anxiety of having to live such a life. The lungs of the planet, the forests, are being destroyed for human profit. Simultaneously, humanity gets a lung disease called Covid-19. We tear baby cows away from their mothers, and we think very little of tearing migrant families apart from each other at our southern border. Can we see the parallels that what we do to the planet we do to ourselves. Our choices have far reaching consequences. Can we see them?

About the Author:

Daishin McCabe of Zen Fields in Ames is a 200-RYT Integral Yoga teacher, which he completed in 2011, and a Trauma Center Trauma Sensitive Yoga facilitator (TCTSY-F). He is a dharma heir of Dai-en Bennage Roshi, with whom he trained in monastic residence for 15 years; he has also practiced in Japan at several training temples and with Ven. Thich Nhat Hanh in France. He has a B.A. in Religion and Biology from Bucknell University. Daishin also teaches at the Shogaku Zen Institute and World Religions at the Des Moines Area Community College. He is grateful to be a member of the Pure Land of Iowa community in Clive, Iowa, where he also offers meditation retreats.

Daishin McCabe of Zen Fields in Ames is a 200-RYT Integral Yoga teacher, which he completed in 2011, and a Trauma Center Trauma Sensitive Yoga facilitator (TCTSY-F). He is a dharma heir of Dai-en Bennage Roshi, with whom he trained in monastic residence for 15 years; he has also practiced in Japan at several training temples and with Ven. Thich Nhat Hanh in France. He has a B.A. in Religion and Biology from Bucknell University. Daishin also teaches at the Shogaku Zen Institute and World Religions at the Des Moines Area Community College. He is grateful to be a member of the Pure Land of Iowa community in Clive, Iowa, where he also offers meditation retreats.